In Plain Sight at McClain Gallery, organized by Aaron Parazette, is an exhibition of 40 paintings by 40 Houston artists. Its essential premise, apart from a group photo-op, is that painting is alive and well, and the reports of its demise have been greatly exaggerated. Its thematic heft—principally offered by Frances Colpitt’s catalogue essay—follows the tune of the new normal in contemporary painting, in which all is permissible, painting has outlived the kangaroo courts bent on its demise and florid representation and post-painterly abstraction now enjoy long romantic walks together. That nondenominational thread and the inarguable—40 artists, 40 paintings, Houston—premise would seem an unlikely rhythm to lose, but even simple melodies can drift off-key.

Where it sticks to what it knows (in this case, the prismatic multiplicity of abstraction), the exhibition remains largely slick and untroubled. Balloon Framing (2010) by Brian Portman is among the show’s cast of gems. In this frenetic oil-and-acrylic on canvas, mark-making is judiciously balanced against restrained, spirit-thinned crimson and emerald stains, layered, worked and repeated upon a neutral and starkly contrasted ground. Doubtless days or even months in the making, its nearly performative irreproducibility and self-cohesion, nevertheless, convey the sense of a spontaneous, ecstatic conception.

Marcelyn McNeil’s Untitled (2012), however much more reservedly cool than Portman’s, is another standout. Here, her collage-painted, oil-black form of disharmonized curves and corners, and incidental color punctuations suggesting mass and motion, is understated and handsome, and might have been stripped from the very collective unconscious of Motherwell and Diebenkorn.

Gael Stack’s Untitled (2012) provides an arresting oil on canvas whose methods are exclusively whisper and insinuation. Composed in deep violet hues with the character of a blackboard plane fogged by wiping, Stack’s marks imply diagrams, angles, equations, structural drawing and the vestige of a solitary human form. Her lines are skeletal, practical, illustrative; but elusive and incomplete. In this way Stack creates the sense of chronological strata, which however indistinct, remain impermeable.

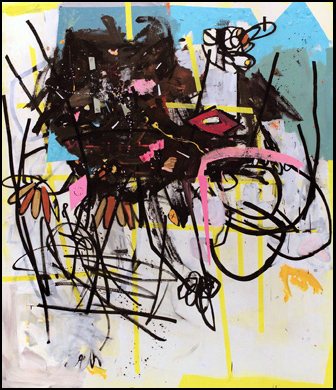

The me that you know is made up of wires (2012) by Howard Sherman is a study in suggestive, revisionist urges. Working in acrylic and marker on canvas, Sherman implies a figurative dimension: an animal form, a clutch of feathers in Hanna-Barbera brown, a hand, a head perhaps—and then alters, defiles and conceals them. Working and reworking so that nothing distinct remains but a record of thought obfuscated by amendment.

Perhaps less ambitious, Kyle Young’s Dialogue Revisions (2012) is nevertheless another satisfying example. Here, Young works densely layered and textured acrylic in deep orange and vermilion, parses an initial composition into six clause-like pieces, reorders them and re-adheres them. Relative to the mood and complexity of the others, it is simple, immediate and pleasing.

Geometric abstraction on the other hand—a mode seeming close to the exhibition’s heart—bears fewer examples, as well as a reduced success rate. Lacking the manifesto-compressed atmospheres which once fostered it, geometric abstraction of the contemporary wilds suffers a shrinking authenticity, and a formula which is volatile and difficult to strike upon. Aaron Parazette’s own offering is among the fortunate. Color Key #55 (2012) is a work composed in acrylic on linen and taking a page from Mondrian, re-interpretively folds from it a neoplastic origami. Parazette plays with the traditional grid structure and color palette of blue, black, yellow (and red) on a white ground; transcribing them to form a plane composed of triangular shapes and the persuasive illusion of depth.

Along these lines is also Harvey Bott’s interestingly titled Roar Schock Well (2012). Bott, however, works in co-polymer acrylic and vinyls in a tighter, more literal Stella-esque vocabulary of violet pinstripes and close, circular gyrations.

Christian Eckart too, addresses the form with his 3 Unit Superimposed Circuit Painting, 2006. It is a work of green, red and orange, rounded and superimposed circular sculptural bands—whose almost singular defense is a pretense to painting, and whose pretense to painting is suspect—which will doubtless please the bank tellers of its future home.

If however, the exhibition’s geometric abstraction is hit-and-miss, its figurative work seems a hasty addendum. Offered in two basic varieties, ironically saccharin or undercooked, both feel obviously unsteady relative to more sure-handed company.

Whatever the premise, the contemporary group show remains a bit of curatorial roulette. And despite its best efforts to sidestep matters of vexing thematic complexity—an effort in which it largely succeeds—the exhibition is nevertheless marked by a curious stillness. For all its interdisciplinary polish, there remains that silence of dissimilar people gathered with no greater purpose than a place in time. A possible virtue of this pageant-like simplicity is the sense of anonymity meted out amongst the contestants, such that high and low, mighty and meek are shouldered together with perfect égalité. Another consequence, however, is the air of a conversation cleaved mid-thought; leaving each artist’s work to stand apart from its motivations, theories of process and broader articulations.

This last, though perhaps a plague common to group shows, nevertheless produces acute symptoms. For example, Mark Flood’s lace painting The Things (2011), strongly invoking Max Ernst’s decalcomania paintings and depicting two bodies suspended from a gallows in a distant foreground, while otherwise ripe with probing melancholy here loses its voice, stammers and seems quaintly folksy.

Similarly, William Betts’s Frigate (2011), depicting a small naval ship as through the frozen moment of a frame capture, sheds much of its foreboding of suspended action. Amidst such disparate company, the Betts, as with the Flood, is compelled to offload consideration for method and message, and comes to read as largely slippery and clinical whereas independently, either are taut and emotively textured.

Taken in sum, In Plain Sight is an exhibition of uneven virtues; a testament to Houston abstraction and to the notion that simplicity often lies in symmetry rather than reduction.

In Plain Sight

McClain Gallery

September 8, 2012 – October 20, 2012

Coverage of Houston artists has been made possible in part by the William A. Graham Fund.

______

Hesse Caplinger writes fiction, essays, profiles and criticism, and is currently based in Houston.

2 comments

“Bott, however, works in co-polymer acrylic and vinyls in a tighter, more literal Stella-esque vocabulary,” says Hesse Caplinger. Guess he did not read Casey Stranahan’s book on HJ Bott’s Displacement of Volume Concepts or Kelly Klaasmeyer’s review of Bott’s work that stated: “In 1952 Harvey won a $5000 scholarship to the then Art Center School of Los Angeles (Art Center College of Design) in his first year with a series of tape drawings that presaged Frank Stella.”…just sayin’.

The figurative work wasn’t odd company to my eye and certainly not ‘obviously unsteady’. Your implication that superior works suffered for their proximity to figuration or otherwise slightly different company reads to me like nonsense and confirmation bias. Maybe Flood and Betts should buck-up and make hardier work. And If there was a painting deserving of the descriptive ‘sure-handed’, it was self-evidently Francesca Fuch’s. I thought it was a stellar show, all-around, and applaud Parazette, et al.