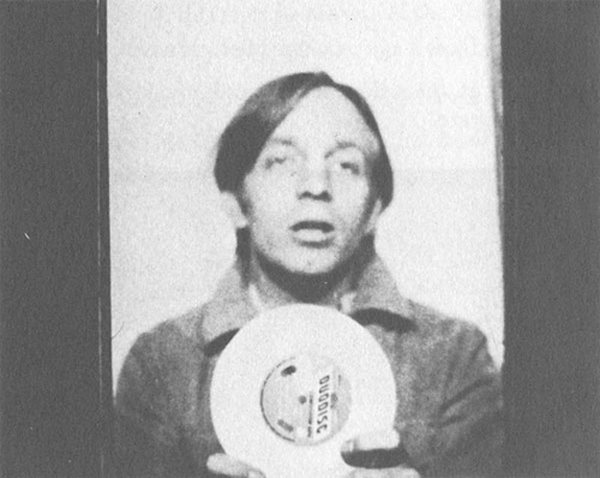

Still from “David Holzman’s Diary” (1967) by Jim McBride. The poster in the background is by Wallace Berman for the 3rd annual Los Angeles Film-makers Festival.

David Holzman (L.M. Kit Carson), the protagonist and “filmmaker” of Jim McBride’s David Holzman’s Diary (1967), is nestled in his West 71st Street apartment between movie posters and art reproductions, windows and mirrors, Eclair 16mm movie camera and Nagra sound recorder. In a mode of direct address he confesses to us—his absent yet implied future witnesses—that he’s 1) lost his job and 2) received an A-1 classification (“perfectly American”) from the draft board. Such is the context on this day—July 14, 1967—of his decision to initiate a film diary.

In an affected Irish accent not repeated elsewhere, Holzman cajoles, “bring yourself into focus…expose yourself to yourself” and quotes Jean-Luc Godard, “film is truth 24-times-a-second.” Given our knowledge that McBride actually is the filmmaker, we glean that “cinema truth” is already under scrutiny.

A narrative (in the form of an enacted diary) that interlopes into nonfiction and experimental discourses, David Holzman’s Diary comprises a treatise of sorts on (the nature of) cinema. By injecting pockets of critical reflection into the “straight” unfettered self-made story of one young man’s life during wartime, McBride troubles conventional narrative’s requisite “suspension of disbelief” while permitting the viewer to lose herself to the “real” of the film if only to continually return.

Beginning with an early slow-motion montage sequence and cycling throughout, the film revels in the geometry and rhythm of 1967 NYC’s Upper West Side: buildings (including Red House built by William Randolph Hearst for Marion Davies), streets and sidewalks, cars, and people. It accesses AV equipment as both production tools and characters. Epitomized by his apologies to them, the camera and recorder are Holzman’s sidekicks. To the extent that it is both a document of the city as well as a film about the making of a film—with a specific focus on the camera operator—David Holzman’s Diary is a descendant of Dziga Vertov’s Man With A Movie Camera (1929).

In a scene at a small park I’m guessing to be Verdi Square (part of notorious “needle park”), the Holzman character is a virtual presence, neither seen nor heard—disrupting but not necessarily overturning the illusion that he (alone) takes us there. In a hand-held hip-level tracking shot the camera walks the park’s triangle of outward-facing benches mostly occupied by retirees. The trees are barren and the majority of those seated wear hats and coats, throwing off our sense of the diary’s authenticity: its July-ness. Faces as a kind of neighborhood map fascinates, this traversal into everyday topography reminiscent of Agnès Varda’s L’Opéra-Mouffe (1958)—with its scan of ordinary residents of rue Mouffetard in Paris.

Responses to the camera are varied: most appear oblivious while some flick their attention upward (onto the face of the passing cameraman) and the few fix fleetingly on the camera. The ethics of the relationship between filming subject and object becomes a specter here…this a time before the advent of continuous surveillance via CCTV and other technologies. Equilibrium is attained when the stainless steel of a phone booth suddenly seizes the cinematographer on his prowl.

A peeping Tom, Holzman ritualistically films a woman in the apartment building facing his. Then there is his fetishistic relation to his model girlfriend Penny (Eileen Dietz), who even when she’s merely a disembodied voice on the phone he can’t stop compulsively recording. And in a classic illustration of the “male gaze” vis-à-vis Laura Mulvey we—from the camera-as-Holzman’s POV—pursue a lone woman out of the subway and onto the street. Although the vigilante bike patrol of Lizzie Borden’s feminist classic from the future Born in Flames (1983) could be summoned to make an intervention, McBride’s film is not without its own disturbance of patriarchal mores: the stalked woman unravels looking relations by abruptly confronting the camera head-on and on another day an acquaintance driving around in search of a “good lay” badgers Holzman on penis size until “the crowd of onlookers got to be too big” and everything became such a hassle that he “terminated the interview.”

McBride punctures Holzman’s solipsism with popular culture and politics, often through innovative pairings of picture and sound. The park scene, for instance, features non-sync sound of (apparently) a United Nations General Assembly vote, “Mexico? No. Mongolia? Yes. Morocco? Yes. Nepal? Abstain.” In another scene, Holzman explains that he has archived the day by shooting one frame of TV per change of picture, the ensuing rapid-fire montage of news, drama, and ad fragments accompanied by absolute quiet.

Place ransacked, equipment vanished, Holzman’s forced to conclude his diary with substitute tools: “I’m at a Duodisc recording booth at the corner of 52nd and Broadway making this record for fifty cents. As soon as I finish I’m going to go over to one of those twenty-five cent photographing stalls and take some pictures of myself with my Duodisc…” In voice-over atop a series of photo booth portraits with Duodisc he bemoans, “this must be the end of the film…I wish I could have learned something…I wish I could have come out….” McBride’s final take on the impotence of obsessive documentation and rampant exteriority to deliver the self is prescient of today’s technological marketplace in which we feverishly compile, disseminate, network, and prove our lives.

David Holzman’s Diary (USA, 1967, 73 min.)

Directed by Jim McBride

Preserved by the Pacific Film Archive

Presented at Stateside at the Paramount, September 4, 2012, Austin

Available on DVD from the library and local video stores

_______

Caroline Koebel is an Austin-based writer and filmmaker on faculty at Transart Institute (New York-Berlin). She has published in Jump Cut, Brooklyn Rail, Afterimage, …might be good, Art Papers, Wide Angle, and elsewhere. Her experimental films and art videos have played internationally, with recent retrospectives at Cine//B (Santiago, Chile) and Directors Lounge (Berlin, Germany). She holds a BA in Film Studies from UC Berkeley and an MFA in Visual Arts from UC San Diego.