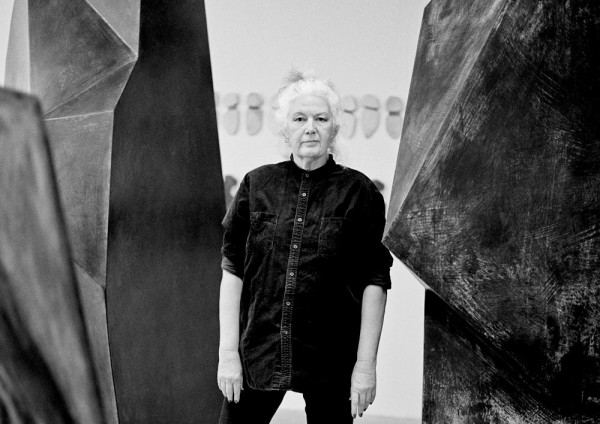

Catherine Lee is a painter and sculptor who has exhibited throughout the United States and abroad. She grew up in Texas, attended university in California and lived and worked in New York for almost thirty years. In the late 1990s, Lee returned to Texas, settling in the Hill Country outside of Austin. An expansive exhibition of her work opens this summer in collaboration with the West Texas Triangle, a group of five museums that includes the Grace Museum in Abilene; the Old Jail Art Center in Albany; the Museum of the Southwest in Midland; the Ellen Noël Art Museum in Odessa; and the San Angelo Museum of Fine Arts in San Angelo. On Memorial Day I met with Lee at her studio where we discussed form and materials, painting, the grid and the spirituality of art.

Katie Geha: You mentioned in an interview that when you were growing up, the idea of being an artist wasn’t something you were aware was possible. So when did it occur to you that you could be an artist, or at least, when did you realize you were an artist?

Catherine Lee: It was a very specific moment actually. I was studying on the West Coast. I was doing all the undergraduate requirements and I was taking art classes as my electives and that’s what I really liked doing. Eventually I ended up majoring in art, but early on I still didn’t think it was something you could do as a career. I had one professor, Sam Richardson, in California and he sat me down one day and he said, “You should do this.” And I thought, “Nah, he’s just chatting me up.” And he said again, “No, really, you should do this.” And that was that. I recognized in that moment that he could see something I couldn’t yet see; I just turned the corner and that’s what I’ve done since.

KG: You are often referred to as a minimalist artist. Do you see yourself as fitting within this group?

CL: Yes I do, and as a post-minimalist, as well. In a way, I think of myself as an abstract expressionist even, but not in the way that most people think of that term. I have a really strong belief in the power of abstraction. My work refers to things in the world tangentially, but it’s not at all representational. I have a very strong allegiance to abstraction and I think that comes from my early upbringing in the Panhandle and El Paso, rather than from an art movement. Where I grew up the landscape was just nothing, it was flat, and there was nothing to stop the wind from blowing through an empty landscape. I’m working from that all the time, a really reduced perspective, a sense of vastness, space. Which made being in New York so hard—it’s extremely vertical and maximal. And what I know in my heart is very horizontal and reductive.

KG: So it’s the emptiness? Or the flat landscape? Or both?

CL: Both.

KG: When you’re making work, are you thinking about horizon? Space in a specific way?

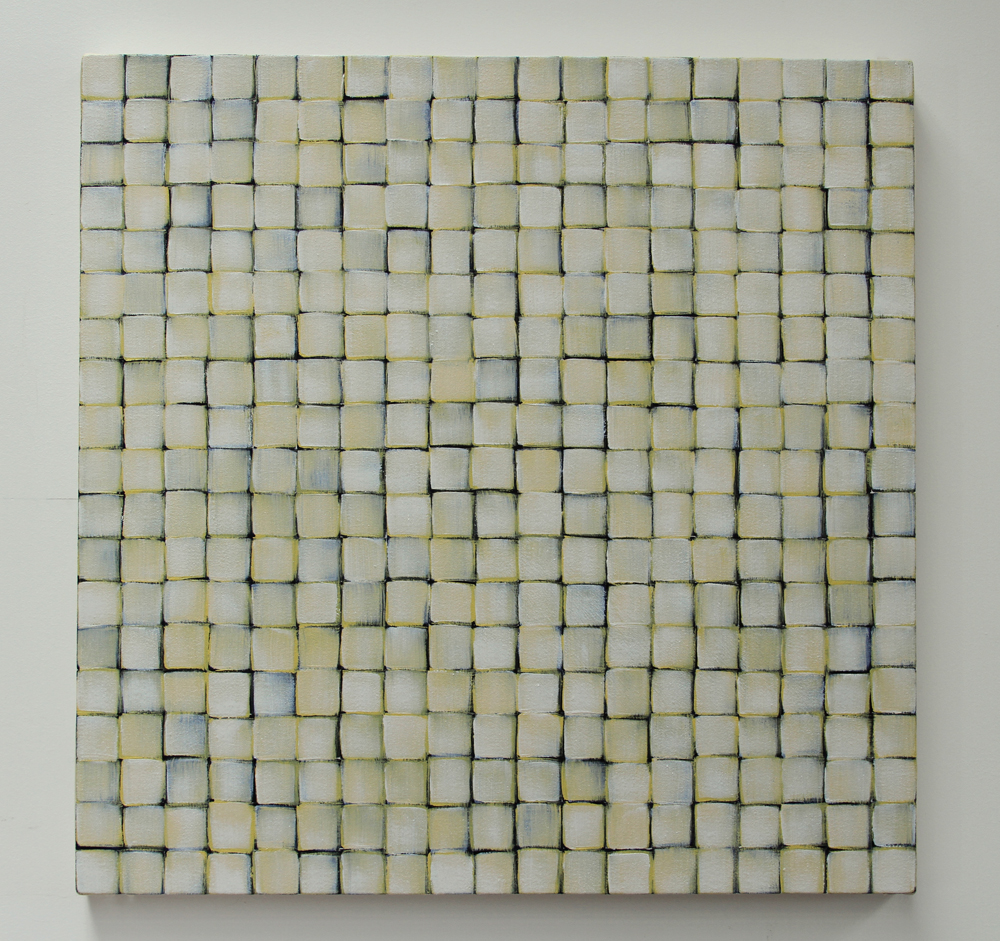

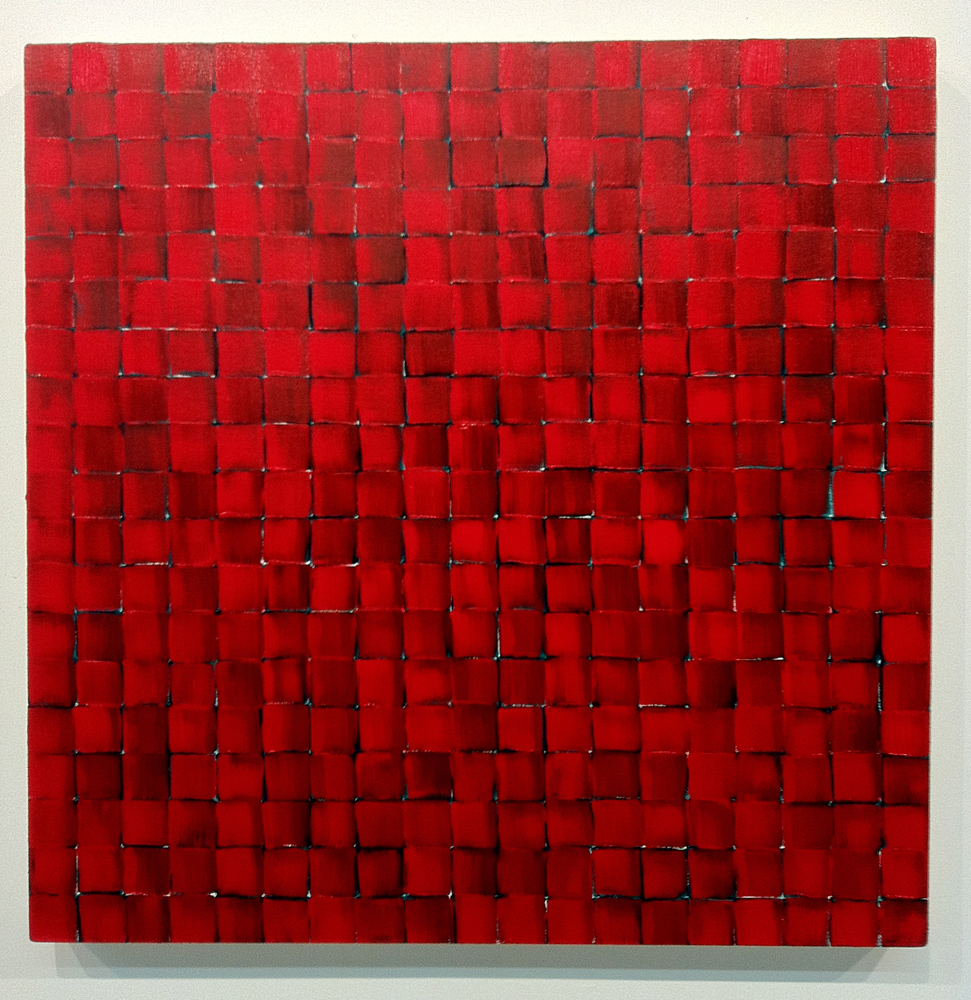

CL: It’s not so much a formal thing as it is just a spiritual thing. The grid is really important to me in my work. Plus I think as a human being. If you’re faced with a blank space, you grid it. It’s the most basic way of making order out of nothing. And so that was my intuition. I made grids and filled them in. And I’m still doing that now, 35 years later. It’s been a constant. My work is always serial, always repetitive; it’s a sort of marking of time, like a record of being in the world.

KG: What are you thinking about when you’re making a grid?

CL: Time mostly. And also how things are the same and different in equal measure. Years ago, in the 1970s, I made grid paintings that were more diaristic, you know, filled in left to right, top to bottom, like writing in a book. You could totally see where I’d stopped or where I had a coffee or where I’d had an argument with someone. But lately I’ve been trying to step back a little and not make it quite so autobiographical. I’m approaching the entire grid at once, in an all-over kind of way, rather than top-left to bottom-right, hoping to address a kind of gestalt of time, rather than a linear reading of small moments.

In terms of what I’m thinking about . . . often times I’ll be thinking about a poem I’m working on, and in that case I may take a line from a poem I’ve written as a title for that painting. There’s a parallel sometimes, just the motion of it, its execution, the dance of it.

KG: Since the recent grid paintings are non-linear, they’re not autobiographical? Because the way in which you fill in the grids, in an all-over manner, negates a narrative?

CL: Yeah, it keeps that day-to-day thing out of it. And it allows for more of a junction of the material and the temporal to occur, which interests me.

KG: You are both a sculptor and a painter. How do those two modes of making function for you? Are they similar? Different?

CL: For me painting is very much more emotionally engaging. With sculpture you engineer and solve problems and the solving of it becomes the focus. With painting it is just you and the paint and you’re just standing there doing this day after day and hour after hour. And the entire time you’re emotionally engaged. There is none of that going off and problem solving.

KG: Do you make sculptures and paintings at the same time?

CL: Yes, and I work with different materials at the same time. And sometimes I make materials live together in a way that don’t want to live together. Like iron and glass.

KG: Do the materials dictate your decision or movement in the making?

CL: It does to some extent. The only analogy I can think of is that it’s like speaking in different languages. There aren’t enough words to say everything you want to say so you have to use them all, and if you can find more, use them too. And I think that’s why I make use of so many materials because you can’t say everything with paint, for instance. It’s just the inflection is slightly different depending on the material. You’re still you and you’re still addressing the same problems, but what can occur has been somehow broadened. I can execute an idea in one material and approach the same idea in another material, and that makes for a very interesting dialogue between those two works, and I do that in the serials from time to time.

Though, when I think of the tools I use it’s not so much paint or canvas or clay, it’s intangible things like repetition and time and constancy—those are my tools and that’s what I’m using and thinking about and not whether it’s a number 2 pencil or number 4 pencil.

KG: So form and materials are less important than the idea of time and repetition?

CL: Yes. When I think about work that I like, it’s almost always something that has a sense of spirit to it. Form is important, or course, but I’m really drawn to . . . I recently went to Utah to see the Spiral Jetty and it was awesome! It’s super reduced and very minimal and yet, it’s such a spiritual place.

KG: I’ve always thought of Robert Smithson as a great Romantic.

CL: Even if it‘s the simplest tool, like a stone axe from six thousand years ago. That is just as moving as any Titian painting. I mean, seriously! I think it is all about intentionality to me, you know, what an artist is attempting in their work. Even if it is a small work I’m creating, I’m trying to make art that has something about it that is monumental in its intention.

Every once in a while someone will ask me where does your inspiration come from and I have to say that I try not to go there. Like don’t look directly into the sun.

KG: But didn’t you already tell me? The landscape. . . Making order through the grid?

CL: Those are components, formal considerations, you know, methodology… Sometimes people really want to deconstruct it, though! They want to dissect it and see how it works. It’s damaging to do that too much.

KG: Because you want to retain some sense of mystery?

CL: Yeah, for myself. I have a tendency to overthink my own work and I have to thwart myself from doing that. I think that throughout history, art has been given to proselytizing, like in the Renaissance, and it’s really not anymore. Once you take the narrative out of it, which happened in abstraction, then you have a whole set of other problems to deal with. You no longer have the narrative so then what do you talk about? There still must be a worthy subject, so what is that, then?

KG: Well, form, the materials, the process. . .

CL: The tenor of it changes. Even the most reduced paintings, the most severe, almost all of the ones that have significance to me have a sense of spirituality: Robert Ryman, Agnes Martin, Blinky Palermo.

KG: I guess I would be reluctant to use the term “spirituality.” I think I know what you mean but it’s not the right term for me.

CL: No, you’re right, it’s a loaded term. But the real problem is when people are making art that looks good but doesn’t have any meaning, or heart, or soul or whatever. It’s a lot easier to do that then to do something that is meaningful. So when I say spirituality, again I’m talking about the artist’s intention, and hopefully that something enlightening or transcendent or moving might be attempted. And even if it falls terribly short, it will probably be imbued with some sense of spirit, even then.

KG: Is it hard to transpose that sense of intention or spirituality to a made thing? Or is it just inevitable in the process of the making?

CL: It’s an event for sure. It’s a thing that either happens or doesn’t happen and you know at the time whether it’s happening. The whole idea of making art, especially the kind of art I make, is generating something out of nothing. It runs right through the spectrum from “hard to do” to “inevitable.” You know what I’m saying? You have to recognize it when it’s not happening. And of course, when it is.

KG: Can you tell me a little more about the five-part exhibition in the West Texas Museums?

CL: It’s a joint exhibition they do each summer, all five museums select one artist to fill several museum spaces concurrently. In my case, the directors all met and agreed that they wanted to show different types of work from different time periods in each of the exhibitions, rather than having the paintings in one museum, works on paper in another, and so on. So for instance, in the museum in Odessa I chose a cast iron repeating series called Doublecross that is 40 units, so it is a long piece that expands 28 feet across the wall. I tried to couple it with other works that would complement that particular piece, like a smaller repetitive work that deals with a similar form but in different materials. From there I went to the paintings and added shaped paintings that I also thought related to the large wall work.

KG: So you’re taking one work of art and putting it in context with other works of art?

CL: Exactly. I’m basically always trying to take the viewer on a journey. Not my journey but a journey together, because I expect the viewer to bring something to the party too, their own thoughts and aspirations and concerns. And that’s what makes abstraction so universally useable, it’s not being limited just to itself. Because at heart, you know, it’s always metaphorical.

____________

Exhibition dates and venues for West Texas Triangle: Catherine Lee

The Grace Museum, Abliene

June 1 through August 16, 2012

The Old Jail Art Center, Albany

June 2 through September 9, 2012

Ellen Noël Art Museum, Odessa

May 31 through August 12, 2012

San Angelo Museum of Fine Art, San Angelo

July 6 through September 2, 2012

Museum of the Southwest, Midland

May 31 through August 12, 2012

____________

Katie Geha is a writer, curator, and art historian living in Austin, TX. She grew up in Ames, IA and received her MA in art history from the Art Institute of Chicago. She is currently a PhD candidate in art history at the University of Texas, Austin. She runs the apartment gallery, SOFA.