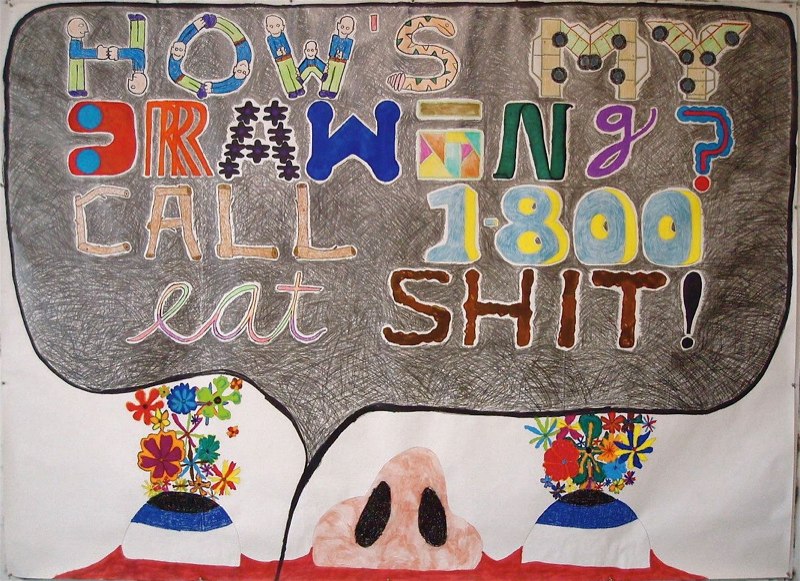

Glenn Downing, “How’s My Drawing?”

Glenn Downing was Texas-born and raised “alongside men with little or no formal education; men who grew up using their hands and got where they were in life by just working themselves to death.” Downing’s pursuit of art led him to UT Austin, Virginia Commonwealth, then to New York where he became an assistant for the late Nam June Paik, a global pioneer of new media. The mix of Downing’s upbringing and art career spur a tangy Texas flavor that respects and relies on the academic establishment while regularly giving it the finger.

John Aäsp: Did you see The Tree of Life?

Glenn Downing: You know I haven’t yet, I’ve read about it, I teach a film appreciation class at MCC here in Waco. I’ve seen all of Terrence Malick’s films. I know it’s supposed to take place in Waco in the 50s. I grew up in China Spring. My dad had a paving company, and later had a limestone crushing plant that was in Crawford. But I had cousins in town so I spent a lot of time riding bicycles through the neighborhoods of North Waco. I also know that from what I’ve read that Brad Pitt’s character is kind of a hard ass, and my dad was one of the hardest asses there ever was.

Glenn Downing, “The World Would Be a Beautiful Place if it Wasn’t For People”

JA: What was the University of Texas Art Department like when you were there?

GD: Basically there were two schools of thought. David Deming and Charles Umlauf were teaching sculpture there at the time. You were either going to make figurative artwork — do clay and then make a bronze — or you were going to do this crazy modern stuff. It was ‘77 so you know it wasn’t that crazy modern, but that’s the way they thought.

Deming did these really nice geometric welded sculptures, kind of a take-off on David Smith. He taught me how to weld. I tried to work like that but didn’t have the craftsmanship. It was bullshit. It didn’t have any life to it. So I just made up my mind right then — that wasn’t what I was going to do. I would go out and get logs and some metal and cut stuff up and jam it together. I did a whole series of this kind of stuff. All of a sudden people started looking at it saying “who’s this guy?”

Glenn Downing, “The Head of Tiny Montgomery”

JA: And what led you to Virginia Commonwealth?

GD: There were seven people teaching sculpture at VCU and I wanted to be immersed in that. I met Lester Van Winkle who was from Texas. We visited his studio and he says, “oh you’ve got some slides, well let’s get some beer and look at what you do.” That formed my opinion right there that I wanted to stay at VCU. Later on Lester and I fought like dogs. I fought everybody because I’m very confrontational — but I think that’s what graduate school is all about. But I felt like they took the work seriously.

JA: How did your work evolve over that time?

GD: Well I was doing sculpture, and I got to where I wasn’t satisfied. I started doing a lot of writing, poetry, stories, anything really. One day Doug Hall came as a visiting artist. He was with these guys out in California — Chip Lord and a couple of others — they had this thing called the Ant Farm. It inspired me to do a performance in my studio, and Doug was there. He critiqued it and gave me a lot to go on. For the rest of my time there I did performance and started using video. I found out I was pretty good at it.

JA: And when did Nam June Paik enter the picture?

GD: Well after grad school I joined the Peace Corps and went to the South Pacific, then lived in L.A. for a bit where I was a house parent for abused mothers and children. Then I came back to Austin for awhile. I went to New York in ’88 and did some odd jobs, but worked in particular with some friends who were moving art around. One of those friends made stretcher frames for an assistant to Nam June.

Shigeko Kubota, Bicycle Wheel, 1983.

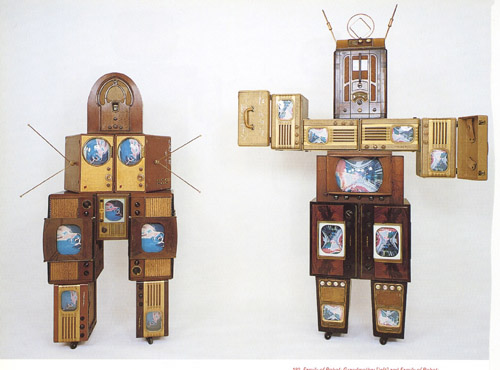

GD: One day this guy asked me if I had a welder. Funny thing is I did. I drug that damn welder all the way to New York from Texas. Anyway, he said someone needed a welder, and it was Shigeko Kubota, Nam June’s wife. The piece was a bicycle wheel that had a TV on it, and it would never work. So she asked if I could make it work. I have this attitude that if somebody asks you if you can do something, you just say “Hell yeah I can do it.” So sure enough, before I knew it that piece became two or three more pieces, and I ended up working in her studio.

Then Nam June came in one day and we met. At some point he just said “By the way, if you have some time, I need somebody to go buy some TVs…” or something to that effect. That’s how it started. I ended up going with him to Korea and Japan and Europe, all over. At the time when he was really rockin’, he had 4 or 5 assistants. We all did certain things and had our own expertise. In 1996 Nam June had a stroke, so for a few years things slowed down while he rehabilitated. But I had been and continued to work for Shigeko all that time.

Nam June Paik, Family Robot: Grandmother and Grandfather, 1986. http://paikstudios.com

JA: And you came back to Texas?

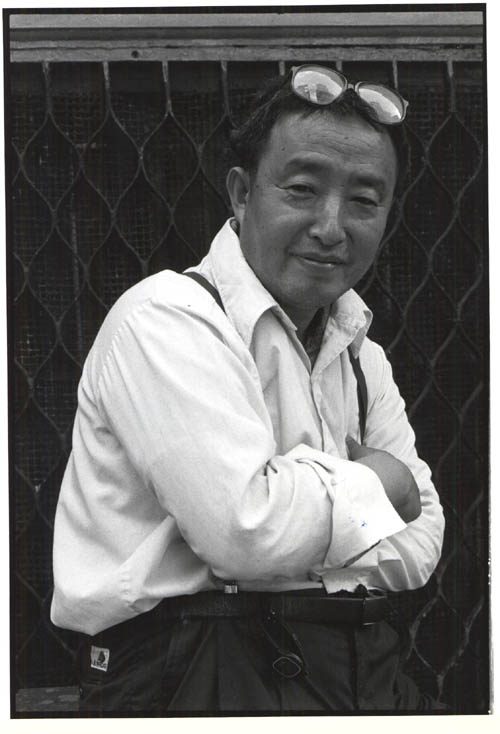

GD: A year or so before Nam June’s stroke I had come back to Texas, but I continued to work on Nam June and Shigeko’s projects, so I’d build stuff and send pictures and we’d talk about it. It was easier to do down here than in New York really. We call it making city money living in the country. But I started going back and forth around 2000, maybe twice a year or so working on various things. Nam June finally passed away in 2006.

JA: Is it possible to sum up your experience with Nam June Paik?

GD: He was a nice guy. A great guy. That’s the best compliment you can give to anybody really, that they were a good person. He wasn’t somebody who was arrogant or had some kind of ego. That wasn’t the way he was. He was an innovator. I really think he changed art. Funny thing was that Nam June wasn’t that technical. He had ideas. I think that’s why we got along. He would get the right people to help him with the technology. He really had kind of a junky way of putting stuff together, and we related in that respect because that was my way of putting things together. He wasn’t a micro manager. The crew would know exactly what to do, no matter where we were. He trusted us.

Nam June Paik

GD: And you know, we wouldn’t sit around and philosophize about art. I’ve eaten more lunches with Nam June and Shigeko than most anyone else in my life, except maybe my parents. That’s what we liked to do — sit and have a big lunch and drink coffee and beer and have dessert — I mean we went the whole nine yards. That’s where all the planning took place. A lot of people don’t know who they are I’m ashamed to say. I think Bill Viola put it best when he spoke at Nam June’s funeral. He said when you went to the top of a snowy mountain and saw footprints ahead of you, those were Nam June’s footprints. The rest of us just followed. Nam June blazed the path.

JA: Why did you return to drawing after working with one of the world’s most innovative new media artists?

GD: Well, I came full circle. I don’t consider myself any kind of artist really. I just think if I want to do something, it has to be done in a certain medium. A drawing has to be a drawing, and drawing is liberating. I don’t need to have an idea. I can create while I work, kind of like making music. It’s easier to get the ideas out.

Still from Jackelope, 1975, dir. Ken Harrison. http://texasarchive.org

JA: What is it about Texas and the art world?

GD: Back in the 70s I looked at a movie called Jackelope that really changed my perspective. It profiles James Surls, Bob Wade and George Green. Each one of them is very different, but very Texas. James Surls is one of those artists I’ve always looked to as a great sculptor, drawer, you know. There’s a scene where Bob Wade comes to Waco and goes out with some guys and they blow stuff up, shoot guns at old cars and Wade takes pictures. I saw that as a young artist and was impressed. It showed me that a young kid from China Spring could make art and be serious about it, but you could have a beard, use a chainsaw and drink beer. They were bad-asses. I like that Texas flavor and I don’t see as much of that now.

JA: Do you think Texas has lost its regional flavor?

I think because of the internet every place has lost a little of that flavor. You pay a price for letting the world come into your living room. Some good some bad. But regionalism aside, wherever you are being an artist is inside you. It can’t be taught really. I’m more interested in what’s inside — understanding what making art is about. Once that’s understood then you can be good even if you don’t have the skills. That’s really the battle. I really think of it all like a rock that you throw in the river. That rock came off the mountain and it was all rough and craggy — but once it’s in the river, over time it’s going to get smooth like a river rock. It’s going to take years and years, but it’s going to smooth those edges. In Texas, there’s certain things about the way art has evolved. The edges have gotten smoother than they were. I’m the opposite. I like to think I’m getting wilder as I get older.

JA: I saw a quote about you that said you were “the most under-appreciated genius hillbilly artist from Waco.” What do you think about that?

GD: Well I’m in Waco, I’m definitely under-appreciated (laughs), and the hillbilly part — you know I still have this way of talking and being — I’ve cleaned it up for you a little bit. I grew up around a bunch of construction workers and farmers. A lot of them were pretty wild, and I’ve just become one of those guys. That’s where my inspiration is. When I make work I’m making it for those men that I grew up with, you know just normal people. But what’s sad is those people don’t get my work at all. It takes somebody from the art world to maybe appreciate it. Those regular guys live a hard life, never making much money and maybe never getting to do what they really want to do, and art would be something that could enrich their lives. It would add light to an otherwise dark existence.

Glenn Downing and “The Showdown” at Mighty Fine Arts, Dallas, April 28 – June 3, 2012. Photo by Rosie Lindsey for Dallas Art News

GD: I believe art is life affirming. I think more people would enjoy life if they could appreciate art. And if you explain what you do to somebody, well then they can understand it. It’s getting people to take the time to understand it. I certainly don’t have a problem with being called a genius, and there’s a lot of pride in that. But if you think about it, when you’re a hillbilly it don’t take much to be a genius. But I like that quote. It sums up pretty much who I am.

―

1 comment

Love this interview……hooray for TX artists.