I had the incredible privilege of visiting the community of Tlatelolco last week. Tlatelolco is one of the places in the city that has long been avoided, was falling apart, and known more for its infamous, sordid history rather than its current potential.

Tlatelolco literally sits a few miles north west of the original site of the city of Tenochtitlan and the Zocalo Plaza, the exact geographic area where Cortez met the emperor Moctezuma upon his arrival into the ancient city. It’s safe to say that Tlatelolco would have been a smaller suburb of the bustling city of Tenochtitlan. In fact, it is said that the last battle fought by the Spaniards to finally secure the conquest of Mexico was on the grounds of Tlatelolco itself.

Former Foreign Ministry building and current UNAM Art Museum on the right, Templo de Santiago Tlatelolco on left, image taken from the ruins below.

In the 1960s Tlatelolco was chosen as the site for a housing complex that was modeled directly after the Bauhaus principles of building a socialist, democratic society with functional and minimalist architecture. Currently, the main plaza of Tlatelolco, or La Plaza de las Tres Culturas, is the hub of the housing complex. The three cultures actually refer to the three defining histories that comprise contemporary Mexico: The indigenous, the Colonial, and the Modern. All three sit in a complete architectural juxtaposition and incongruency with one another that is only normal in current day Mexico. On one side of the Plaza is a towering skyscraper that was built in the mid 50s as part of the housing complex and soars above the ruins of a small indigenous city that was clearly razed when Spanish conquerors erected a small church directly on top of the pyramids.

The juxtaposition of the three is extraordinary. It’s no secret that cultures and histories have indeed clashed in bloody wars over the centuries in Mexico, but the presence in Tlatelolco is only more shocking given the depth of the history of the area.

In 1968, only a few days before the summer Olympics in Mexico, an estimated 10,000 university and high school students gathered in peaceful protest against the spending the government had put into Olympic preparations. On October 2 thousands of students gathered in a peaceful protest. As a result of mounting international pressure in an escalating and tense situation, then president Gustavo Díaz Ordaz ordered the student protest to be quelled in any way necessary. What occurred was the massacre of innocent student protesters, the arrest of many more, and an extremely painful moment in Mexican history.

Plaza de las Tres Culturas, with site-specific installation Raíces by José Rivelino snaking through the plaza.

Tlatelolco slowly began to empty after the massacre. The area received its final blow in 1985 when the infamous earthquake rocked the city to its core. Two of the towers in Tlatelolco fell to the ground completely destroyed, and others were left extremely damaged. Tlatelolco was one of the hardest hit areas in the entire city. Thick, white cement brackets hold walls together, and thick cracks run the length of the plaza as remnants of the earthquake. Afterward, residents began to vacate slowly throughout the years., government buildings were left abandoned, and Tlatelolco gained a reputation for being destitute and bereft.

Recently the government gifted one of the abandoned buildings to the National Autonomous University (UNAM) which has begun investing in the area and bringing it back to its former glory. The university has converted the building into an art museum, and has invested in a site-specific public sculpture that runs throughout the entire plaza.

Cuentos Patrioticos, by Francis Alys, a video created by the artist in 1997 as a response to the 1968 upheaval, and on view in the commemorative exhibition at UNAM's art museum in Tlatelolco.

installation view of protest posters in the commemorative exhibition at the UNAM art museum in Tlatelolco.

Protest flyer translated as "this is the only public dialog that we have had," on view in commemorative exhibition at UNAM art museum in Tlatelolco

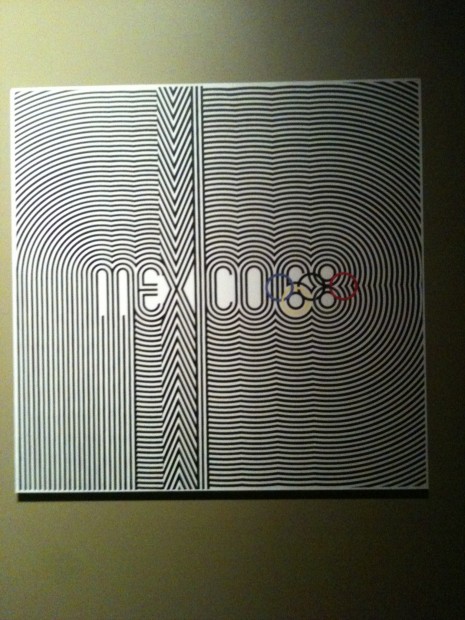

Poster for 1968 Olympics in Mexico, on view in commemorative exhibition at UNAM art museum in Tlatelolco.

The pain of the history of Tlatelolco runs incredibly deep, and thankfully will not be forgotten. It’s hard to avoid the sentiment of astonishment and anguish when walking through the Plaza when the realization hits that young people died there only a few decades ago. The entire experience was a humbling one in the way that only history can humble. The juxtaposition of pride and embarrassment associated with the events in the area is conflicting, confusing, and worth a conversation. The work being done by UNAM in the area is worth diffusion, and watching Tlatelolco grow to its former glory is worth the attention.