El Anatsui has been a superstar in the art world ever since the 2007 Venice Biennale, where he received international acclaim for his large-scale sculptures made from thousands of discarded metal liquor bottle tops. In these pieces, the tops are flattened and stitched together with copper wire to form lush, shimmering canvases of intricate pattern and color. The transformation of rigid metal into something supple and the transformation of mundane, discarded tops into something monumental has made these signature works some of the most recognized by a contemporary artist living in Africa. Yet his watershed Biennale moment and continuing success has obscured the fact that Anatsui has been making work for over 30 years and was already an artist of international importance (just one who may not have always commanded quite as high of prices). The retrospective exhibition, When I Last Wrote to You About Africa at The Blanton Museum of Art in Austin is an extraordinary glimpse at the breadth of El Anatsui’s work since the mid-1970s, long before he brilliantly began stitching bottle tops together in 2002.

When I Last Wrote to You About Africa is a traveling exhibition largely culled from El Anatsui’s personal collection with some works from private collections. It has been put together by Lisa Binder of the Museum for African Art in New York. The selection of work and extremely well executed installation at The Blanton reintroduces an artist many of us might think we already know. I shared this sentiment, having worked with El Anatsui on a site-specific installation at Rice University Art Gallery in Houston in 2010. Stepping into the show, I realized that I actually had no clue just how dense with cultural and personal meaning his work was, or how varied it was, from sculptures in wood, ceramic and metal to two-dimensional paintings, drawings and prints.

The exhibition is not arranged chronologically. Instead, everything reverberates formally and conceptually; mediums, subjects, styles and time periods mix. The associations that can be made outside of a rigid, didactic chronological presentation are especially fitting for Anatsui, who sees things in a radically open and unfixed way. One of the most unusual qualities about him as an artist is his egoless insistence that curators rearrange and install his metal sculptures in new ways. He wants them to determine how works fold, or how the individual pieces of wood that make up a larger piece are to be arranged. I remember him at Rice Gallery playing the role of a reticent conductor as he composed his installation on site. He gave basic direction to achieve his overarching vision, but was also pleased with the unexpected notes his orchestra of assistants might give him. For Anatsui, materials acquire value through their use, and this belief has often led him to select found or discarded things to work with. It stands to reason that he might think of his own art in somewhat the same way; he hopes each curator displays them or “uses” them in a new way.

The first sculpture of the exhibition, Wonder Masquerade (1990), is a perfect embodiment of this philosophy. This figurative sculpture is made from individual strips of curved wood that are scorched and singed with thin, burnt indentations that form lines and symbols, characteristic of much of Anatsui’s work in wood. In this showing, the strips of wood have been stacked vertically to form a subtle curve along the sculpture’s edge, creating an elegant riff on a cloaked figure. Flanking this sculpture on the surrounding walls are one of the signature metal pieces, a couple of relief-like wood pieces and a painting.

The selection of work is an immediate introduction to Anatsui’s impulse to endlessly abstract ancient African symbols and ideograms of the Adinkra, Nsibidi and Uli languages. Akin in spirit to how Cy Twombly plays with the calligraphic mark, Anatsui rides the tension between a written symbol’s legibility and its abstraction in dense fields of repetitive mark making and geometric patterns of color. But it doesn’t matter whether you can decode these symbols or not. The pleasure of the retrospective is seeing a masterful artist at work. Anatsui is comfortably grounded in so many different identities, yet never content with one, as he virtuously wrestles with different materials. Anatsui simultaneously looks backward toward his own ancient culture, yet also forward toward immediate experience, creating new forms of sculptural assemblage.

This especially hit home for me after visiting the second floor of the Blanton, where a metal bottle top sculpture of Anatsui’s (which is not in the retrospective but in the Blanton’s permanent collection) is shown next to a Yayoi Kusama, a Richard Long and an Anselm Kiefer, among other contemporary artists. I found the relationship to Anselm Kiefer especially powerful. As I wandered back downstairs to see the retrospective again, I saw more closely how Anatsui was similarly plunging into cultural and personal history to create contemporary artifacts out of the transformation of materials.

In Akua’s Surviving Children(1996), Anatsui made a grouping of abstracted figures out of weathered, round logs of driftwood while he was at conference about slavery in Copenhagen, a place that had been a large part of the slave trade industry. Anatsui found the driftwood on the beach, and it brought to mind the journeys of slaves torn from their roots. He then made the nails used to fix the heads onto the bodies in a forge that had once been used to make weapons during the slave trade. He charred each figure’s face black to “cleanse them,” as he describes, and then grouped them in a procession-like arrangement. The piece evokes a painful, traumatic history, yet manages to avoid fatalism and instead focuses on survival and renewal.

In contrast to the somber and contemplative works, there’s also plenty of joy. One great pairing is the sculpture Open(ing) Market (2004), which is placed on the floor and adjacent to a playful metal work on the wall called Zebra Crossing III (2007). For Open(ing) Market, Anatsui commissioned tinkers (people who make things out of tin) to make nearly 1,700 small tin boxes lined with advertising labels and magazine ads. The small tin boxes and three larger suitcases all sit on the ground and face the same direction, with their lids cocked halfway open. The experience is like peering down on a mini-market, bustling with color and text. When you move to the other side of the sculpture, the backs of the boxes and lids are painted black and dotted with hand-painted, red crescent moons, possibly alluding to the idea that when the boxes close, the market does too.

Deceptively simple and fun, the boxes still embody deep meaning, speaking to the traditional (an open air market of exchange), the cyclical (night to day) and to something profoundly modern (the collision of cultures, as some are even lined with Coca-Cola stickers and StarKist tuna labels). Zebra Crossing III is equally visually engaging, with strips of flat black bottle tops mixed with gold and purple, to make stripes of black that mimic the stripes of a zebra and imply movement as the color and pattern vibrates and shimmers.

After taking in the full exhibition, I saw the work that seemed the most familiar—the metal pieces using discarded bottle tops— in a new way. The brand names that could still be seen on some of the tops, such as Black Gold, Dark Sailor and King Edward, pointed toward a dark past of the liquor and slave trade, but also to basic ideas of exchange echoed throughout Anatsui’s other pieces about movement, migration and change. When stitched together, the color and patterns of the metal bottle tops have visual allusions to kente cloth, but also a distinctly topographical quality where they sometimes look like maps.

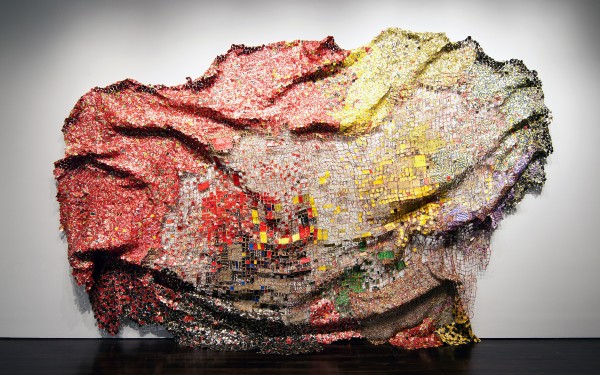

The most recent and largest metal piece, Stressed World (2011), which was commissioned for the exhibition, looks like a sagging land mass or continent just hanging on, but not quite collapsed, as the metal folds droop from the wall and drape onto the floor. Many different parts of the metal bottle top are manipulated to create patches of checkered squares of red, black and yellow, and also open rings that form a net-like weave of thin lines. Stressed World is near some of Anatsui’s earliest works where he used ceramic and manganese to make what look like broken pots. He says about these pots, “I regard my process as an exhortation; that things have to break in order to start reshaping.” It’s a beautiful idea, not only when you look at Stressed World and think about El Anatsui’s personal experience in Africa, a continent ripped apart by colonialism and ethnic conflict, but also as you look at his retrospective as a whole. You see how it goes so much deeper than coaxing beauty out of a bottle top; it shows how an artist found transformation and even joy out of pain and destruction.

Joshua Fischer works as the assistant curator at Rice University Art Gallery. He graduated from Trinity University, where he double majored in Studio Art and Sociology. He then received an M.A. in American Studies from the University of Texas at Austin.

10 comments

Plese post the schedule for the traveling exhibit if possible!

Great article Josh! I enjoyed El Anatsui’s work for the first time in Washington DC. I will have to make a trip to the Blanton to see this powerful art again.

great article on profound work. thanx

Wonderful and vivid review! Makes me really want to see the show. Well done, Josh!

Great article Josh. What a wonderful insight into El Anatsui’s world and how his environment has affected his artwork. I need to get to Austin to see the show!!

Thank you all for your generous feedback. I appreciate you taking the time to read the review.

Judy, here is the schedule you asked about:

North Carolina Museum of Art

March 18 – July 29, 2012

Denver Art Museum

September 9 – December 30, 2012

University of Michigan Museum of Art

February 2 – April 28, 2013

I found this on the Museum for African Art website: http://www.africanart.org/traveling/11/el_anatsui_when_i_last_wrote_to_you_about_africa

Lovely exhibit. Please feel free to share our post about El Anatsui and his work which features a rare interview with him. The video was made when the exhibit launched the World Premiere in Toronto.

http://myetvmedia.com/feature/el-anatsui-an-introduction/

I love the deep and wonderful expressiveness.

[…] Even the draping of the “tapestries” speaks volumes in each work . “Stressed World” was stretched and pulled taught, yet sagging under its own weight. Lulling waves swelled in “Oasis.” “Tahari in Blue” was somehow formal with its thick, crisp creases. “Susuvo” fluttered like a regal flag. I was surprised to discover that such installation choices were likely made by the curator rather than the artist, as explained in Glasstire’s article about the exhibit. […]

Dear Josh:

I also attended U.T., Austin the received my Master of Libral Arts from Johns Hopkins University. You might be interested in visiting my collection which goes into storage over the next two years, a perfect time for an exhibition should you become interested.

Sincerely,

R. Edson