I’m a lucky guy. I’ve already outlived Doc Holliday by twenty-four years and just the other day I came upon a new Randy Wallace piece, Postdimensionalman, at Trinity University in San Antonio.

More and more, Mr. Wallace seems like some sort of metaphysical signpost, standing at an invisible point of observation from which he conducts his singular vigil. Only occasionally there may be a glimpse of crossed arms, with hands and fingers aimed one way and the other, but each time this apparition appears anew, it seems to be pointing in different directions yet again.

The last thing I notice upon exiting Postdimensionalman is a spray painted “SAYONARA” on the back of a temporary sheetrock wall seen through a floor-to-ceiling window of the gallery. It’s a final goodbye to three friends recently departed. It waves a see-you-next-time as I walk away, all the while sending that same last goodbye, the one that waits for all of us.

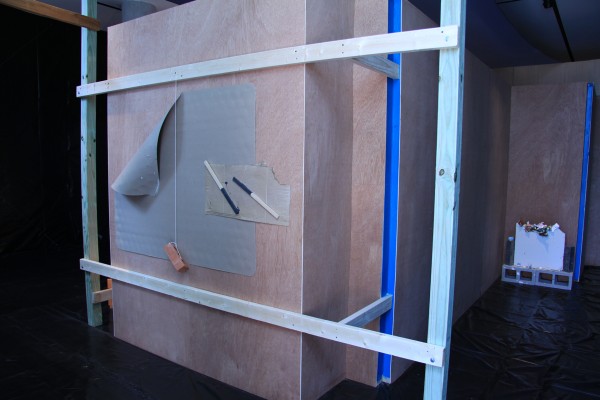

Just as I am about to exit, I stop and notice the corners where the walls of the installation come together. The maze-like layout of the piece leads you into various interiors and hallways, so the outside of one serves as the inside of the other. Various surfaces cover these stick-framed walls, but in this case the skins stop short of the outside corners. These exposures are painted turquoise, the color of adoration. And how finely do these rough-framed two-by-fours dovetail with the words of architect Louis Kahn, who said, “Ornament is the adoration of the joint.” I’ve often pondered the truth in this phrase and at this juncture I also notice that these painted corners call to mind the unprotected knee-backs, ankles and elbows of a suit of armor. From this I conclude what we all know: Reality leaks. But we need that vulnerability so that we may keep dancing.

At the end of a narrow, luan-lined hall, a plywood scrap is balanced on two concrete blocks. Numerous broken tchotchkes congregate on the plywood’s top edge, their precariousness evidenced by the surrounding scattered shards. These broken knick-knacks, mostly cast in the forms of cats and birds, are a mono no aware tableau of interdependence and impermanence. A delicate parlance.

Mounted on an adjacent perpendicular wall: a piece of found cardboard, about three by four feet, appearing to be some sort of packing material. A quarter of it is folded down and stapled. A brick hangs from a string out front, revealing gravity, adding depth. Another scrap of cardboard, with discarded paint stir sticks stuck to it, completes the collage. This last is salvaged from the floor and by virtue of its upright installation, adds a bit of vertigo, counteracting gravity, flattening depth. The arrangement looks almost trompe l’oeil, that is, without dimension, like some kind of M.C. Escher illusion, but done by a proxy hand, perhaps that of a creature assembled from spare parts.

The snapshot is of a photograph that hung on the wall in a Pacific Northwest hospital room. Part of the image is burned to white from the reflected glare of a window, but this luminous void fits comfortably into the composition behind a row of pines. The snapshot is attached near the center of a wall covered in black plastic. Two strings cross the wall diagonally from opposite corners creating “cross-hairs” that are not centered on the wall, but on the white void, thereby suggesting that this space is to be read as some sort of passage or portal. This de-centered intersection forms the locus of observation, a looking through nature to something perhaps lying spellbound within it. The glance must bounce off the surface of reality not in the way that light bounces off it, but at the acute angle that allows a look through.

A cicada lies in repose, entombed in a squat mason jar. It rests upon a white cotton glove, delicately veined wings intact. The glove is of the type favored by those who handle art with care. Colloquially called a locust, this cicada does indeed serve as yet another locus, this time focusing our attention not on the white beyond, but on the It of it, the insect, defying all names. The jar hangs from a string, countering the dead weight of the brick hanging on the other side of the wall. It is suspended in black space suggesting sepulchral solemnity. The artist found the creature dead just outside (not the artificial outside, just down those steps, but in the outside outside, beyond the glass). He had heard it alive the day before. I asked him how he knew it was the same one. Said he did.

A large format Plexi-laminated photo is propped on a base, leaning against the wall, thus simultaneously occupying the illusory space of a painting and the actual space we stand in. The image of a moss colony overtaking other plant life is inter-cut with the image of an outdoor handrail wrapped with yellow plastic caution tape, creating a diagonal merger between images that both call to protection and distress. The byproduct of the alliance is yet another vanishing point, one that lies in limbo, between illusion and actuality.

The Metropolitan Building, a neo-gothic and long empty hi-rise built in Detroit in the mid-twenties sits on a triangular lot. It used to be where timepieces were assembled, but its interior was rendered toxic from the manufacture of luminous watch dials. Here, in a photograph framed alongside wadded sheets of discarded newsprint, it is split by a pie-shaped slice of a museum text referencing Doris Salcedo’s “Untitled (Armoire),” a sculpture made to honor those Columbians who have “disappeared.” The lines of visible text get shorter and shorter as they descend into the point of the triangle, so only a few words of this sentence appear: “The empty chair is there, screaming the absence of that person.” All that can be read is, “the empty chair is there.”

The clean room is a place where systems of counting and classification seem absurdly complex compared to the two simple door jam lines that quietly mark the heights of two lost friends. They also mark where the real intercedes into art, beyond all design by the artist. In this room, endless pieces of Zorock, a decorative garden rock made of recyclable material, are trayed, counted, bagged, photographed, sorted, matched, numbered and mounted in an array of intention overwhelmed by futility—the posted numbers that cover every vertical surface peter out in the 3000s, filling the room to capacity. Yet there are so many more Zores to go, and by implication there are more coming in the endless stream of matter that transfixes us. Count we may, but never will we bake everything into a pie.

First thing, you put on shoe covers. Something needs protection. There is a ramp to a deck, a hybrid of interior and exterior space, vaguely loft-industrial. You might be drawn to the clean room, or to the split Metropolitan or any of the other vignettes that guide you through these facets. These are zones where meaning yields and accrues according to your efforts. It is an ongoing meditation on the twin desires to live and to be gone. The burden of materiality is still seen as an opportunity, an exercise in fertility, even though it must eventually be abandoned for something post dimensional.

Randy Wallace: Postdimensionalman

Trinity University Gallery

September 15 through November 19, 2011

_________

Lubbock native Hills Snyder lives in San Antonio. He is an artist, curator, song writer and director of Sala Diaz. You are invited to follow his writing on the Facebook page U.S. 87.