In 1994 a cave was discovered in Southern France containing paintings dating back about 32,000 years. Christened the Chauvet cave after one of its discoverers, the cave and its paintings – the oldest known on Earth by double – are so fragile that only a handful of scientists are, and ever will be, allowed inside.

The Chauvet cave is long and deep, divided by several pitch-black chambers. Paintings were made by hand, finger, and stick along its curving walls, with animal imagery the dominant figuration. It is great art, not just because it is ancient, but because it is technically complex, beautiful, and specific. A herd of horses is layered vertically along one surface with so many nuances of shading and detail that each individual steed must have been personally known to the artist. Another wall perfectly outlines a male cave lion with a single horizontal line six feet long. A bison is painted with eight legs, suggesting movement in a precursor to animation. A rock near the cave’s entrance is covered in red circles, all proven to be the handprint of one man, six feet tall with a crooked little finger.

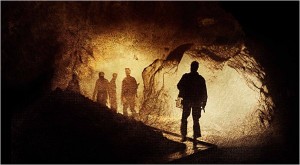

Filmmaker Werner Herzog and his three-man crew were granted limited access to shoot the Chauvet cave. The result is Cave of Forgotten Dreams, a visually opulent knock-out of a documentary that tries to understand the creative vision of cave artists across an abyss of thousands and thousands of years. Serving as our tour guide and narrator, Herzog is giddy at every turn, and I was, too. “Are these paintings the birth of the modern human soul?” he asks. Yes, Werner, yes!

The film was shot in 3D, but Dallas’ arty Angelika shows a standard 2D version. My first viewing was there, and though the film was great, I felt tech envy at deep, lingering shots of glittery stalagmites and wavy cave walls with ancient cracks and scratches from livid cave bears. So I trudged all the way to Plano to watch it again in 3D. Not only were the 45 minutes in transit worth it, but my fear of Kung Fu Panda’s soundtrack bleeding through thin walls were totally unfounded. Herzog uses long moments of near-silence to fine effect, and the Plano Cinemark respects that.

With the 3D situation in hand, we the viewers are virtually placed in the space of the Chauvet and film-watching transcends one of its few limitations. Cave bear skulls become porcelain sculptures. Echoes register. Herzog is the most sensory filmmaker around today (and probably ever). He even attempts to compensate for our inability to smell the cave by letting a “master perfumer” tag along on a shooting day, hoping an expert nose can describe the cave’s odor (“subtle” is the chosen word). The perfumer is an odd bird, as is one archeologist whose last job was circus performer.

When the circus-juggler-turned-archaeologist begins explaining his work in the cave, Herzog shouts out, “BUT WHAT WERE THEIR DREAMS?!” His question gets to the heart of this film and all of Herzog’s work, or at least the films I’ve seen (though I concede I have no theory on Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call – New Orleans, but still, it’s pretty awesome). Back to the point – Herzog loves the misfit. Grizzly Man, Land of Silence and Darkness, and the fictional, weird-as-hell Even Dwarfs Started Small explore (exploit?) the outcast who fails to connect with society but dreams of nothing else. With Cave of Forgotten Dreams, Herzog desperately wants to connect with whoever we were 32,000 years ago, using art as the connector, and the film is all the more beautiful for acknowledging its own failure to do so.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eNlxiJFvwUA