Yesterday at the Glasstire panel discussion on regionalism at the Modern in Fort Worth, Art Guy Michael Galbreth repeated over and over that “artists care about the world” — that they are looking to the world and their experience of it, and not to other art explicitely, for information for art-making. This is true. I recall with some nostalgia those blissful, uncomplicated years in college when I had eons of studio time to fiddle with the mess on my table and the mess in my brain — all gathered from the world — and patiently carve out a future in which, I was sure, I would be an Artist with a capital A, with space to think and make.

Fast forward nearly a decade and I find myself sans studio (unless my dining room table counts,with an old sideboard serving as a flat file), with little space for the sort of leveled, slow-paced thinking that being an artist requires. All this has something to do with the children I now have underfoot — offspring, friut of my loins, thorns in my side, balls on my chain, pains in my ass– wonderful, harebrained and dazzling little creations that have made life ponderously cumbersome, mathematically complicated and, subsequently, infinitely more rich. But the artist part is wanting, though the world chugs on around me.

If we do look to the world as artists, as Galbreth says, we are looking there for encouragement as much as we are for information — for other artists to serve as models for our particular way of being in the world, which is an odd, wonky feeling most of the time, at least for me. Since becoming a mother and struggling, by and large unsuccessfully, to balance the plates — nurture the urge of making and putting things into the world (besides children) while managing the other stuff of life — I’ve always looked to Barbara Hepworth. Without a wince and with smooth grace, Dame Hepworth spun those plates despite divorces, the death of a child, the long-illness of another, war, prejudice and all those personal human foibles that could leave a gal strung out and crazy. She just made it work, and I’m grateful to her for her total commitment to each of the hats she wore. She kicks me in the pants, through her beautiful work and words, on a regular basis.

So Happy (Art) Mother’s Day, Babs. Thanks for jabbing me in the ribs your example.

– I loved the family and everything to do with them. I loved the environment and the cooking. I used to cook and go in my studio. I had to have methods of working. If I was in the middle of a work and the oven burned or the children called for me, I used to make an arrangement with music, records, or poetry, so that when I went back to the studio, I picked up where I left off. I enjoyed it, you see; it was part of me.

(From “Art Talk, conversations with 15 woman artists”, Cindy Nemser 1975, Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data, 1995, p. 14)

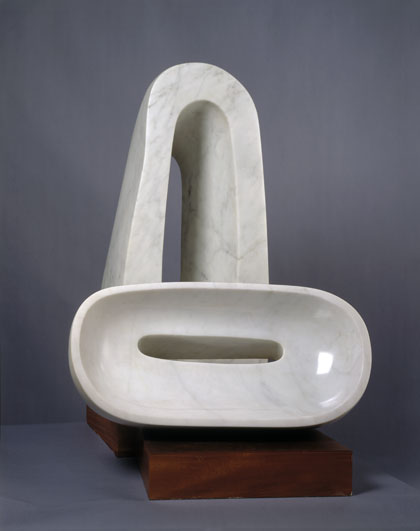

– Our sense of touch is a fundamental sensibility which comes into action at birth – our stereognostic sense – the ability to feel weight and form and assess its significance. The form which have had special meaning for me since childhood have been the standing form (which is the translation of my feelings towards the human being standing in the landscape) the two forms (which is the tender relation of one living thing besides another); and the closed form, such as the oval, spherical or pierced form (sometimes incorporating colour) which translates for me the association and meaning of gesture in landscape; in the repose of say a mother and child… …In all these shapes the translation of what one feels about man and nature must be conveyed by the sculptor in terms of mass, inner tension, and rhythm, scale in relation to our human size and the quality of surface which speaks through our hands and eyes.

(From “Barbara Hepworth, A Pictorial autobiography”, New York, Praeger Publishers, 1970, p. 284)

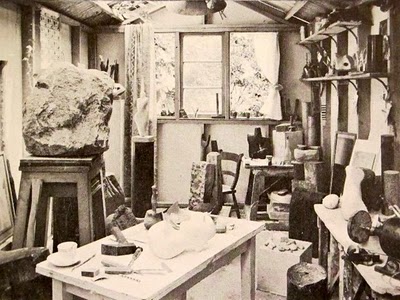

My studio was a jumble of children, rocks, sculptures, trees, importunate flowers and washing.

(From “Barbara Hepworth, A Pictorial autobiography”, New York, Praeger Publishers, 1970, p. 283)

Wave, Plane wood with colour and strings, 1943–44 (BH 122), Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh

– There is an oval sculpture of 1943. I was in despair because my youngest daughter, one of the triplets, had osteomyelitis. In those days the war was on and you couldn’t get anything. She was ill for four years. I thought the only thing I can do to help this awful situation, because we never knew if it would worsen, is to make some beautiful object. Something as clean as I can make it as a kind of present for her. It’s happened again and again. When my son died, he was killed (in the war, fh), it’s the only way I can go on.

(From “Art Talk, conversations with 15 woman artists”, Cindy Nemser 1975, Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data, 1995, p. 19)

– At no point do I wish to be in conflict with any man or masculine thought. It doesn’t enter my consciousness. I think art is anonymous. It’s not competitive with men. It’s a complementary contribution. I’ve said that and I do believe it, that one does contribute to art and that’s nothing to do with being male or female… …I don’t think a good work of art can just be said to be feminine or masculine… art’s either good or isn’t.

(From “Art Talk, conversations with 15 woman artists”, Cindy Nemser 1975, Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data, 1995, pp. 15-16)

all images via Hepworth Estate, except Hepworth’s studio shot which is via Mondoblogo

1 comment

THANK YOU for the beautiful reminder!