The implosion of the Austin art world has got me thinking about art world power dynamics, as I mentioned last week in my published correspondence with Rachel Cook. The resignation of Blanton director Ned Rifkin and deputy director for external affairs and operations Simone Wicha’s instantaneous appointment to the position, the elimination of Arthouse curator Elizabeth Dunbar in favor of Sue Graze’s continued reign, and before that the resignation of long-time AMoA director Dana Friis-Hansen, all of these stories are partly about shifting power dynamics. Whether we’re artists, curators, directors, or supporters, these events underscore how necessary it is to be aware of sources of power and influence as we navigate the art world.

Recently, I read Jeffrey Pfeffer’s Power: Why Some People Have It—and Others Don’t (Harper Collins: 2010) for a class with (Texas native) Cade Massey. The book, and the course in general, has given me an opportunity to think about sources of power and influence within the art world more broadly. I’ll share some of my thoughts here and hope they provide a jumping off point for conversations over pizza and pitchers at Salvation or stiff drinks at the Driskill bar.

One caveat before I begin. I intentionally do not make value judgments about the contemporary art world’s structures of power here. I simply attempt to untangle them. I’m hoping that my thoughts provide you with a useful framework for assessing the lay of the land around you and, in particular, your position within it.

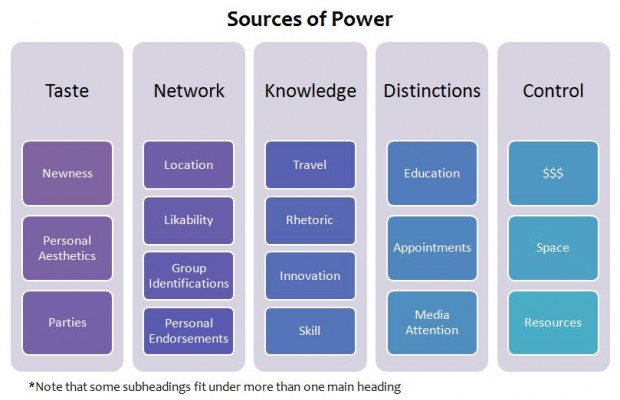

Hypothesis: power in the art world is acquired primarily through taste, networks, knowledge, distinctions, and control of resources. I’ve broken this down in the figure below.

Taste

Taste, a superior aesthetic sense, is a key to power within the art world. (Think Bourdieu’s cultural capital.) It is, in a sense, the most significant type of “expert power” within the field. Taste is not limited to the formal aesthetics of a painting, but also includes political taste, intellectual taste, and cultural taste (for example, in cuisine, dress, or hobbies). Taste sometimes has to do with fashionableness, but they are not perfectly correlated. Tastes vary within the art world, but there is an acceptable range within which they remain, (at least until you are a “taste-maker,” which requires the acquisition of power by other means.) In part, taste has to do with signifying upper-class status or a close relationship to the upper-class (as when a relatively poor artist receives wealthy collectors’ approval for “being in good taste.”)

In “The Coppola Smart Mob,” The New York Times gets at the heart of these questions when it quotes Wes Anderson on Sofia Coppola, “’Sofia has uniquely great taste,’ Anderson says, which, given the way Coppola works, is at once a compliment to her and himself.”[1] The perception that Sofia has taste is partly dependent upon her network and her referent power as a Coppola. The extent to which tastefulness can be cultivated independently of network is unclear.

Taste is acknowledged as the legitimate source of power in the art world. The logic goes: art is aesthetics,[2] therefore, aesthetes must control it. In some sense, “taste” is the art world’s logical explanation; if a curator rises to the top of her field, the justification is that she possesses superior taste.

Network

The center of the contemporary art network in the U.S. is New York as represented in Artforum’s Scene & Herd. After New York, Los Angeles forms the second-largest node in this network, with cities such as San Francisco, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Houston forming smaller hubs.

A curator who relocated from Austin to Manhattan two years ago recently told me, “New York is the most provincial city in the United States.” I took this to mean New Yorkers only pay attention to New Yorkers. If you are not living there, you’re not much worth their time. This is an exaggeration, but reflects a truth about how close-knit the New York art world is.

In my experience, the contemporary art network functions much like Coppola’s in “The Coppola Smart Mob.” There is little distinction between friends and colleagues. People work together because they like one another, and they like one another’s taste. Philanthropists often give partly because they like you or because you are a link in their network—for example, they are on your board largely because of who else is on it. Institutional employment is often obtained through recommendations among friends. This is partly because the quality of an artist’s or curator’s products is difficult to assess. Thus, individuals in the art world have a tendency to turn to those who have already been vetted by those closest to them. The existing network is self-reinforcing

There are many players in the art world, among them artists, collectors, gallerists, curators and directors. Because each party has very different stakes in the project of art production and dissemination, making things happen is often largely about mediating among parties that possess divergent interests. The ability to understand all viewpoints is important within this process. A successful “rainmaker” must understand and align the interests of the philanthropists and foundations paying for the exhibition, the artists in the exhibition, the curator putting together the exhibition and the institution at large.

Knowledge

The contemporary art world has many similarities to academia with respect to the relationship between power and knowledge. Theory has assumed a central place in art production. Individuals can gain respect through facility with the language of theory, with the history of art, and the popular texts of the moment. The culture privileges new ideas and innovative uses of old ideas. (A year ago, I would have attributed this to the legacy of the Avant-Garde. After spending a year in business school, I attribute it to the incessant drive of capitalism.) Rhetorical flourish (in catalogues, art journals, artist talks) magnifies the impact of most good artworks and exhibitions.

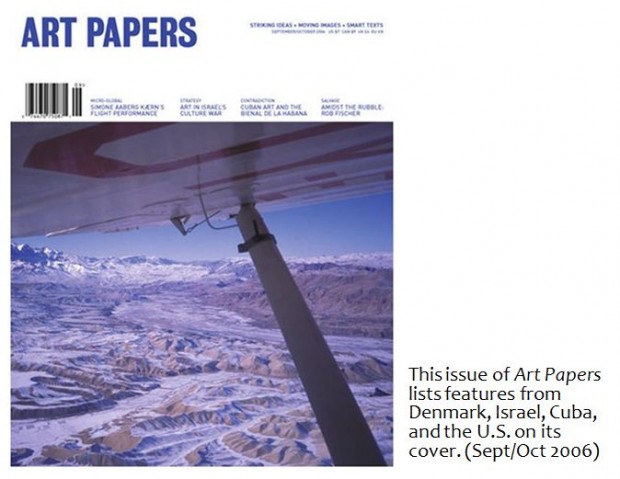

People in contemporary art also seem to gain respect through international exposure, a type of knowledge of the world. A collector who has attended the latest biennial, an editor who juxtaposes a review from Singapore with two more from Accra and Birmingham (see the cover of Art Papers below), a director who spent two weeks of vacation touring Thailand’s DIY scene, these types grow in the estimation of others. Knowledge of the international art world is important.

Skill, or applied knowledge, has a role to play in the acquisition of power in the contemporary art world, as elsewhere. A deftly executed drawing or good-looking financial statements can draw positive attention to an artist or director, respectively. But, as always, skill only gets you so far without other mechanisms of power and influence.

Distinctions

Titles and distinctions are an important part of getting your foot in the door and creating a positive first impression, though they may not take you much further. I have noticed that those who receive one honorific tend to attract more. When grants, fellowships and awards come with resources attached, these can be a source of power.

Media attention can also garner more attention and respect from colleagues.

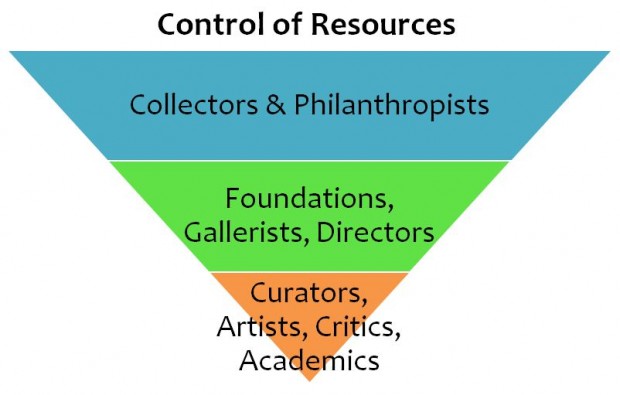

Control of Resources

Resources are limited in the art world, even more so than in the for-profit world, and particularly now after the financial crisis. The most critical resources in this world are money to make work and space to show work. Other important resources include in-kind donations of materials, services, and expertise, and opportunities for exposure such as speaking engagements and press. Figure 4 sorts the actors in the art world according to my view of how much influence different actors in the art world have over resources.

So What?

What kind of power matters most? It depends. In fat times, resources are abundant and taste may reign supreme. But in today’s skinny times, control of resources may be trump. No matter what, a robust network and the ability to build coalitions are prerequisite. In both the case of “Rifkin v. Wicha” and of “Dunbar v. Graze,” cultural capital lost to control of resources. Rifkin and Dunbar have pedigreed publishing and curatorial experience. Wicha and Graze have serious fundraising chops and reputations for getting things done. (Wicha was development director for the Blanton prior to being appointed deputy director for external affairs and operations last year.) Also in both cases, the victor possessed a longer-term network in Austin. Wicha preceded Rifkin by four years at the Blanton, and Graze preceded Dunbar by eight at Arthouse. Twice in a matter of weeks, deeper regional networks and control of resources took the day.

I’m not saying this is bad, just that it’s true. Understanding these kinds of power dynamics is crucial to navigating the art world with grace. I’m hoping you can build on the framework I lay out here and shift your sails to navigate just a little more gracefully.

[1] Lynn Hirschberg, “The Coppola Smart Mob,” The New York Times, August 31, 2003, accessed via http://www.nytimes.com/2003/08/31/magazine/31COPPOLA.html on April 23, 2011.

[2] Again, not just formal aesthetics, but political etc.

Claire Ruud received her M.A. in art history from The University of Texas at Austin and is pursuing her M.B.A. at Yale School of Management. Claire is currently researching the predictive power of financial ratios in the performance of nonprofit arts organizations

4 comments

I wonder if recent discussions about talent verses capital plays into this discussion.

http://blogs.forbes.com/evapereira/2011/02/16/malcolm-gladwell-on-why-income-inequality-is-the-next-big-issue-facing-america/

If it does, then the triangle would be inverted. That is the salaries and costs associated with artist’s works, curator’s exhibitions etc.. would drive the control of resources.

Claire, thank you for your time and effort this. It is fascinating to see the art system analyzed and quantified to a certain extent.

I enjoyed the article. Thank you for publishing it. Please address the loss of Dana Friis-Hansen to AMOA. Dana at one time possessed all of the collateral you speak of, but seemed to lose control of resources with the opening of The Blanton and the redo of Arthouse.

What could/should have been done differently? What should AMOA be looking for in its next hire?

Si Elle

WOW! For now. More later.