Recent events (scandal?) at Austin’s Arthouse have provoked plenty of public and private conversations amongst artists and curators in Texas and beyond. The duo Cook & Ruud, recently separated by graduate school (Rachel Cook is at Bard in curatorial studies; Claire Ruud is at Yale in business school), have been engaged in conversation around the topic, too. The following is a series of emails sent back and forth to one another discussing the Arthouse situation with an eye to the broader environment in which artists and curators operate today and the implications of this environment on their curatorial/arts management practice.

More detailed information on what happened at Arthouse can be found on …might be good, Glasstire, and austin360.com but here are the salient points: Arthouse has been accused of censoring the video work of Michelle Handelman in response to concerns voiced by some Arthouse board members and of illegitimately renting out Graham Hudson’s installation to Warner Music Group without the artist’s permission. Both exhibitions were curated by Elizabeth Dunbar, Arthouse’s former curator and associate director, who objected to the way the artists’ work was handled. Last week, the Arthouse board eliminated funding for Dunbar’s position after the Arthouse board requested that the organization find ways to trim the budget, Arthouse director Sue Graze eliminated funding for Dunbar’s position – thereby eliminating Dunbar and the position itself.

April 14, 8:03 PM

Dear Claire,

For a moment, I want to try to look objectively at the series of events that recently transpired—in the last week when so much became public, but in reality the events leading up to Elizabeth Dunbar’s departure have been going on for months if not years prior—in our former burgeoning art community. If I can, I want to stop thinking about this as choosing sides, pointing a finger of blame, or any of the other host of impulsive responses that happens in a confrontational situation like this one.

As a former resident of Austin—I still feel connected to this art community, watching these events from afar has been difficult and struck an emotional cord with me. I found it hard not to get drawn into the fight, even when I started with what I thought were the best intentions. As I take a step back and reflect on the physical distance between the community and me, I realized that this is how most of us watch volatile events that happen around the globe from the comfort of our own home while sipping our morning coffee in front of a computer screen. Ideally, this distance allows for a greater perspective.

What I’ve found fascinating about watching these events transpire is how visible the power dynamics within arts organizations actually are. When researching in an archive, we are taught to look at the documents to see what information is inside of them, but also to look at how they are separated, and mostly what is missing. What is missing from all the discussion about this situation is the question, how has power been wielded to gain financial resources or for self-protection instead of for founding mission statements? Decisions are being made for marketing reasons, such as rumors of hiring a PR firm for damage control, or emergency financial reasons, such as acquiring rental fees. These are not content-driven decisions, and they certainly don’t sync up with creating meaningful opportunities to investigate and experience the art of our time.

I’m wondering what you’re thinking about all this. Write soon.

Rachel

April 15, 7:47 AM

Dear Rachel,

Is there really an objective position on this situation? I’m going for thoughtful, measured, and balanced, with a view to the big picture. But it will be subjective. I have opinions, and I probably don’t have all the facts.

I agree, we talk way too little about the power dynamics that are at play within the art world. Resources are scarce right now (thus the appeal to financial motivations), and that’s often when power dynamics matter the most.

But I’m going to push back against your suggestion that jockeying for power under financial constraint necessarily leads to decisions that don’t support the investigation and creation of contemporary art. Hierarchies and politics are inevitable, no? If you don’t try to obtain power within the system, someone else will. In the nonprofit art world, this creates two problems. First, service of the larger purpose—the creation and presentation of art—is often seen as antithetical to the power game. Second, the people who are most uncomfortable with the acquisition of power are the most liberal supporters of the most experimental art. Thus, the directors, curators, and board members who are most comfortable acquiring power are the most comfortable exerting control over the artistic object.

I’m speculating that this is what happened at Arthouse. I’m dying to know whether Elizabeth Dunbar and the group of board members who are uncomfortable with the instrumentalization of Graham’s work and the censorship of Michelle’s could have (1) felt more entitled to take control of the situation earlier, (2) built coalitions and jockeyed for power, and (3) prevented the poor stewardship of the institution and the art in its hands.

In the U.S. more broadly, a conservative backlash is clearly at hand. These are issues we’re going to face ourselves. As future curators and directors (I hope ☺), we have to be willing and able to acquire and wield power in order to preserve the integrity of our institutions. Otherwise, someone else—probably someone who feels uncomfortable with a little dildo action—will.

Sorry to go all Machiavellian on you. I’ve been reading The Power Broker for class.

Claire

April 15, 10:35 AM

Claire,

A conservative backlash is a perfect description for what is happening. Maybe an objective perspective is not the right term, so if sticking to the big picture is more apropos than I am interested in breaking down some of these power dynamics that I see. The division between cultural workers (staff of Arthouse and Austin spaces in general) and cultural supporters (board members of the organization, collectors, donors in Austin) is the most intertwined relationship in this situation. At first glance the two categories might appear to be similar; they attend the same events, go to the same parties, volunteer their time, lend an ear—but the difference is money, plain and simple. The cultural worker can’t go to Venice Biennial unless they get a grant, work more hours, or get a cultural supporter to pay for the trip.

It is this division that created a misunderstanding of the Facebook page that was created in response to recent events as well as comments about Arthouse’s upcoming fundraiser 5 x 7, which frankly wouldn’t be financially viable without artists donating 100% their time, labor, and creative piece of art. I was so shocked that members of the board of Arthouse took the criticism of Arthouse as artists trying to dismantle the organization. I took the gesture of the Facebook page as artists finally standing up to the organization and saying we might still contribute, but we are going to tell you what we think at the same time. We do live in the land of freedom of speech, right?

So not only is the organization saying we would like to limit or alter the creative voices of Michelle Handelman, who recently won a Guggenheim for her work, and Graham Hudson, whose rights to the control of his own work have been violated by Arthouse; but they’re also saying, we need artists to donate a 5 x 7 artwork. This is a perfect example of a broken model for an arts organization fundraiser event. For years artists have given in to the promise of exposure, connections, visibility with their 5 x 7 board or 8 x 10 entry, all for what, a free ticket to the event itself? And sometimes not even that, now it is the discounted later night entry, or the $25 artist evening. How is that helping the artist’s exposure, if you are limiting their access to cultural supporters? Right there is an economic and proximity division that is clearly set. The cultural supporter needs to understand the levels of disrespect that go into helping an organization create an event like this. And yes, since the cultural supporter is in a position of authority, they DO have a voice to change this policy.

The drive of production and consumption in today’s capitalist societies creates an enormous amount of tension about how art objects and artists are produced, displayed, and consumed. Arts organizations should see themselves as promoters of knowledge and gift economies, rather than trying to follow the capitalist model for production and consumption of artworks. While artworks might be bought and sold within gallery walls, they do not function the same way as capitalist goods.

It is the idea of a gift economy that Arthouse and other arts organizations should be reading more about, to better understand the nature of caring for and thinking about artworks. Coincidentally the term “curator” goes hand-in-hand with the idea of caring for and thinking about art. I still don’t understand the decision making process that goes into limiting something from view, altering a sculptural installation, and not communicating with the author of the artwork. All of this points to a strong misunderstanding of both the term “curator” and the perceived role of the curatorial on Arthouse’s behalf.

Look forward to hearing more of what you think, and great to see what you are reading too!

Rachel

April 15, 6:18 PM

Rachel,

Tell me what to read about the gift economy. Yes, it’s frustrating that finances have become such a constraint over the past few years that leaders have more than once compromised the curatorial and artistic integrity of their institutions. What’s so interesting to me about this conversation is the tension between idealism and realism you and I are playing out. Because of where each of us is right now, you’re holding more of the visionary and I’m holding more of the practical. So I’m going to push back again because the tension is super productive for me. Hope it’s not irritating. Ready?

Who cares about the curator and the curatorial if there is no $$$ to support the project? You can only function in a gift economy for so long—it’s rewarding in an emotional, intellectual, relational sense, but it is also exhausting to live on $30,000 a year amongst the upper and upper-middle classes. At the same time, I’m not suggesting the “tight budget” excuse can or should be played as a trump card every time.

My impression is that there are people at Arthouse, on the staff and board, who understand how to respect artists and be good stewards of art. My guess is that the problem is an inability or unwillingness to talk about mission and money in the same breath. We can’t pretend they’re not deeply intertwined. Perhaps before the financial crisis, organizations had the flexibility to neglect financial planning in favor of mission, and post-crisis, we’re seeing organizations and their funders swing too hard in the other direction (woe to you should your program expense ratio fall below 75%).

It’s almost schizophrenic. Mission. Money. Mission. Money. The schizophrenia allows leaders to subconsciously or consciously avoid the money until the last minute. Then suddenly the money is urgent. And then suddenly the budget is slashed, without any public discussion of possibilities, or even much of an internal discussion within the organization.

Last week, I attended a workshop with the Nonprofit Finance Fund, and something we saw there immediately came to mind when I heard about the budget cuts. We looked at the (anonymized) financials of a couple of nonprofits the Fund has worked with after capital campaigns. It’s not unusual for nonprofits to be brining in huge surpluses during a campaign like the one Arthouse just went through, only to realize later that they’ve actually been running a serious operating deficit. That is, cash is coming in at a rapid rate to support a building project, for example, but some of it is actually being spent on salaries, keeping the power on, programming, etc. without anyone inside the organization really keeping track. For this reason (and because they often fail to fully account for all the additional operating costs that come with expansion), it’s not uncommon for nonprofits to experience serious financial difficulties (particularly in terms of cash flow) after expanding. I wouldn’t be surprised if this is part of the issue at Arthouse.

To me, Arthouse’s financial situation is symptomatic of a larger reactive (rather than proactive) culture and schizophrenic (rather than integrated) approach to mission and money in the nonprofit world. I want this to change. I want to start talking about mission and money in the same breath. I’m hopeful that if we do that, we might come up with more creative solutions to the relationship between the two.

Claire

April 16, 10:21 AM

Claire,

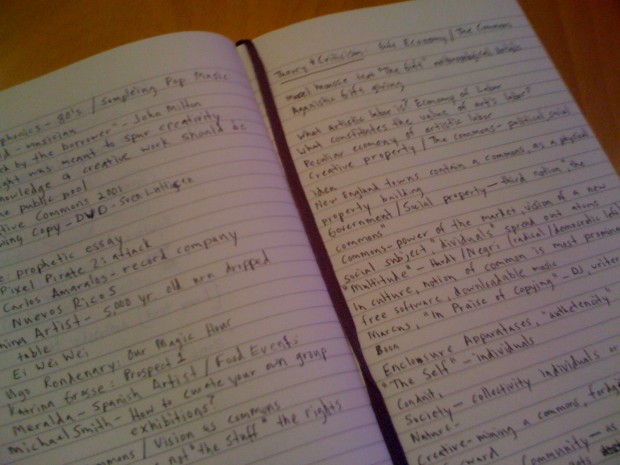

The Gift: Creativity and the Artist in the Modern World is the book by Lewis Hyde. He also recently published one around the idea of the commons, which is just as, if not even more, interesting a concept to think about in terms of something that is not owned by the market or the government, but by the people. It is called Common as Air: Revolution, Art, and Ownership. Would be great to hear what you think about it, but back to the task at hand.

I agree the cycle of money and mission is a catch-22 with any arts organization. However, I do believe that eliminating the entire position of curator and associate director does not follow their mission. The curatorial role is not part-time nor does the parachuting in approach of guest-curators create a more nimble organization. This creates chaos for your local community audience, there is no sense of continuity, and conversations cannot be built over time. Maybe in the late 90s early 00s this technique was more appropriate with the rise of independent curators and the sense of bringing the outside global conversation to the local level. I am attending a graduate program for curatorial studies, and am I to believe that to be valuable to an arts organization, I have to be independent, without health insurance, wandering from project to project on flights or always in transition, rather than embedded within a community being able to have conversations with artists, writers, and peers?

Now in this age of globalized art communities, why would any foundation support an organization that has decided to evacuate the role of a permanent curatorial voice not only in the programmatic structure, but also as associate director of the organization? Are we saying that we can cherry pick our content off of the jpegs or lines on a resume of the outside voice, and the role of the curatorial has nothing to do with creative problem solving on the day-to-day level? Creative thinking can allow for a variety of different things to change, not just picking from a who’s who list to help fill your gallery walls, floors, time, and space.

Today, when every arts organization in the country’s budget is getting slashed, it appears investment in local community and a healthy sense of self-reflection is needed. Whether or not you believe an embedded provincial value system exists within smaller art communities, such as Texas, there is a growing conservatism that is running rampant within this country. So how does the small, emerging arts organization see its role in presenting political, sexual, social issues? The question of politics becomes more urgent in a climate such as this. As Karl Haendel once said when asked if he considered himself a political artist, “It’s just a sense of ethics, like, how could you not address politics and still sleep at night?”

Whether Arthouse decides to bury its head in the sand and not publicly communicate with their audience, or pretend all of this will blow over in a couple of weeks, they are wrong. This is symptomatic of a greater problem of power, money, and divisions of labor, the commoditization of artistic labor, and the amazing galvanizing force that a community of artists can bring to the table. There has been a rupture, and one that I fear might be slowly happening across the country in other pockets and smaller arts communities. Our changing society has made all theses issue bubble up to the surface, and it is my hope, and I think yours too Claire, that as part of this emerging generation of cultural workers we understand that we do have a voice, and can make drastic changes in our community whether it is big or small.

Rachel

April 17, 4:10 PM

Rachel,

I agree—these questions about the relationships among people, their labor, money, and art won’t go ever away. And I certainly am on the same page with you RE: eliminating the curator should not have been an option. It is difficult to believe that there were no other creative solutions available to the organization. Questions of money and mission are hard, but Arthouse never gave the public an opportunity to work through them. Even the censorship panel discussion was organized after-the-fact and spearheaded by individuals outside the organization. There are a lot of parties who feel some ownership of Arthouse. But decisions came authoritatively and out of the blue. This is no way to garner public support for tough decisions.

You know, though, I don’t want to harp on the past. I have been trying to think about what I would do in this situation with all this water under the bridge. At this point, what would Arthouse have to do to start rebuilding the trust of contemporary artists and their supporters? (I think that’s the group that has been most alienated by all this.) I’d like to know. I’m going to ask around.

To rebuild my trust, Arthouse would need to immediately:

(1) Publish a policy prohibiting the censorship of artwork under any circumstances.

(2) Publicly apologize and pay Graham Hudson the fees it received from the renting of his artwork, after recouping any costs of the event. (Arthouse’s budget is in crisis, I know. I don’t think this matters. If the institution needs to pay him in small installments for the next ten years, so be it. It’s not Arthouse’s money, period.)

Part of me is tempted to call for a leadership change because of the way the public’s trust has been broken. However, unfortunately, given the lack of a succession plan now that Elizabeth is gone, I think asking for Sue’s immediate resignation would be ill-advised. There have been too many drastic, reactive moves already in this story. I’d like to see things moving slowly, transparently, and steadily for a while.

People’s anger, I think, is primarily caused by the lack of public process around the decisions being made. If Arthouse had announced that it was considering all possible ways to reduce the budget by X dollars, if it had put a variety of options on the table and explained why the decision to eliminate its curatorial position was better than all the rest, people would be disappointed, they would be frustrated, but if the logic was clear and the process was deliberate, people might not be so angry.

Claire

To join in the conversation, feel free to comment below or email Rachel Cook and Claire Ruud directly at [email protected].

(“The Dilemma of Authenticity and Visibility” in the article’s title was inspired by Natascha Sadr Haghighian‘s work.)

Cook & Ruud is a think tank and production team interested in drawing on both non-profit and for-profit strategies to develop new models for supporting contemporary art. Rachel Cook is pursuing her M.A. in curatorial studies at Bard CCS. Rachel is interested in ideas around ambiguity (formally, discursively, politically, socially, or culturally based) and how this framework is a site where fear and loss of control resides. Claire Ruud received her M.A. in art history from The University of Texas at Austin and is pursuing her M.B.A. at Yale School of Management. Claire is currently researching the predictive power of financial ratios in the performance of nonprofit arts organizations

5 comments

A bad economy is no justification for an organization not to manage its cash flow, be it a relatively small arts non-profit in Austin, or a Wall Street bank.

On reflection, it’s not fair to single out Arthouse in this regard. This applies to any art org.

Also: putting the mission before the money is probably more often a cause of problems at art institutions than the reverse. I’m talking about the *real* mission, not the fluffy stated one.

Com’on Rainey, the reason Dunbar

was fired is because she went above Sue’s

head on matters to the ArtHouse Board!

Dunbar is an experienced curator and

should know better!

Why give up a Posh Austin Townhouse

and all the amenities

because you suddenly feel the “urge” that

something is ‘not right’ with

the Austin Art world?

Really? That’s silly.

No one wants to discuss the pink elephant. ArtHouse is known in the art circles to be less than fair with artists. The continued spiral is revealing the venomous underpinnings to an organization and leadership who is out to maintain it’s status- rather than promotion and exhibiting contemporary art. More will come out now that the light is being projected on it…. Maybe even some of the misdealings with AMOA and other underhanded activities of said organization. I hope Glasstire and other art media organizations actually does some more investigative reporting. They will find some great material.

Thanks to Claire and Rachel for this v. helpful discussion.

The organization can survive with less money or with less art; it can’t thrive without a reasonable amount of both.

The executives &/or administrators of an org. are often caught in the middle and don’t always have the leisure to reach the best decisions.

One insight that I think emerges from both Claire’s and Rachel’s comments: that while there are many factors in what may have gone wrong, ameliorating the disfunctionality will require those who believe that the art has not been given sufficient priority to take responsibility to insist on greater transparency, to pay attention, and to exercise their power (often done most effectively by organizing).

It’s not about starting a war; it’s about not being chumps, and restoring a balance of power.

One beneficial result might be to make it easier for org execs/administrators to stand up to the money people.