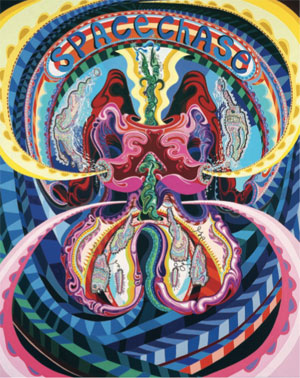

Erik Parker Space Chase, 2006...mixed media on canvas, 84 x 66 in...Private collection, Los Angeles...courtesy of Honor Fraser Gallery, Los Angeles, Calif.

Weird, dreamlike forms that seem to be melting or vibrating, extreme color and kaleidoscopic space are characteristic of psychedelic art, which has usually been seen as the product of popular culture rather than as a persistent strain of contemporary art. Ranging from stroboscopic geometric abstraction to outsiderish magic realism to glitter ball installations, Psychedelic: Optical and Visionary Art since the 1960s at the San Antonio Museum of Art is curator David Rubin‘s in-depth examination of the hippie-era style usually associated with concert posters and album art.

Fascinated by Frank Stella’s Double Scramble (1968), a geometric abstraction that appears to pulsate, Rubin set out to do something that hasn’t been done before, “documenting the origins and development of a psychedelic sensibility in contemporary art.” He uses San Antonio as a microcosm and local artists fill SAMA’s main exhibition space, the Cowden Gallery, while the nationally known artists credited with being pioneers of the psychedelic are relegated to the smaller and somewhat cramped Focus Gallery.

Rubin notes that Stella disdained the “op art” label, though many of the geometric abstractions in “Psychedelic” appear to have similar dazzling, dizzying perceptual effects. For example, Richard Anuszkiewicz, whose Celestial (1966) is the oldest painting in the show, is usually described as a founder of op art. Likewise, Victor Vasarely, represented by the interwoven lines and patterns of Tekkers-MC (1981), is known as a leader of the op art movement, along with Bridget Riley, whose work is in the catalog. Al Held’s giant spatial conundrum Eagle Rock III (2000), in the museum’s Great Hall, seems more in line with Rubin’s idea of “kaleidoscopic space” with endless, hallucinatory depth.

“Psychedelic” is divided between geometric abstractions and other-dimensional paintings, such as Jack Goldstein’s untitled painting based on photographs of outer space, and visionary work that seems more derived from underground comics than the trippy patterns of ‘60s-vintage concert posters.

Alex Grey, Journey of the Wounded Healer, 1985...oil on linen, triptych, 90 x 224 x 2 in. overall...Collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego, Calif., Gift of Linda and Stefan Stux

Alex Grey’s Journey of the Wounded Healer (1985) is the most phantasmagoric painting in the exhibit, a triptych of a male figure with see-though skin sliding down a spiral of DNA on the left, the figure and his ego explodes into thin slices in the middle and then emerges in the right hand panel as a glowing, golden man with transparent skin carrying a caduceus, a symbol of medicine and health. Grey credits a vision he had in 1976 while experimenting with LSD as the source of his inspiration for his mystical, shamanistic paintings.

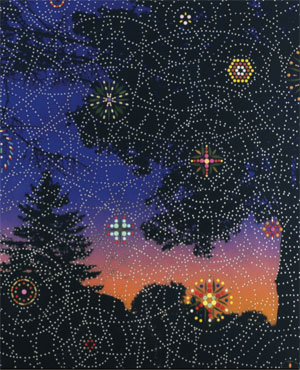

Rubin has been careful to distance the psychedelic style from its drug-induced roots, but Fred Tomaselli makes the connection explicit in Ripple Trees, with psychedelic patterns made with images of assorted pills, hemp leaves and saccharin superimposed over the silhouettes of trees at sunset. Though Tomaselli ended his LSD experiments in 1980, he has said that “tripping gave me a personal relationship to the pre-modernist ideal of painting as a window into an alternative reality.”

Fred Tomaselli, Detail of Ripple Trees, 1994...assorted drugs, hemp leaves, saccharin,...acrylic, resin on wood panel, 48 x 48 in...Collection of Peter Norton

Robert Williams is a link to the underground comic style of the ‘60s, having trained as a fine artist and then worked at the studios of Ed “Big Daddy” Roth, drawing fantastical hot rods and motorcycles for t-shirts and ads. His Lord High Solver of Puzzledom is a portrait of God looking over a jigsaw puzzle for a piece that will complete a nude woman’s behind. The rush of images, from a man being strangled to a shed constructed of puzzle pieces, shuffles perceptions like a deck of cards.

The Cowden Gallery contains a mini-retrospective of artists from San Antonio or with San Antonio connections who reflect a ‘60s sensibility. Alex Rubio’s Chicano noir merges the rippling patterns of psychedelia with realistic imagery, which seems to be melting and oozing. Two drunk donkeys, who might have stepped out of a Big Daddy Roth cartoon, are denizens of his outrageous Burro Land. Albert Alvarez’s paintings are crammed with scenes from a life lived on the edge, a folk art-like cascade of nightmarish visions that seem to teeter between criminality and conformism. Karma and Death Pervade My Consciousness includes the head of a fiery demon, a plane crash, a hold-up and a man having sex with a pregnant woman. Alvarez seems more in touch with the dark side of flower power, or as he says in the catalog, “the spiritual world is not just Bodhisattvas, fairies and angels.”

Erik Parker, who lived in San Antonio but earned an MFA from SUNY Purchase and stayed in New York, pays tribute to the ‘70s-vintage psychedelic space-rock band Hawkwind in paintings that seem like a trip through a wormhole. Michael Velliquette makes Technicolor dreams using shapes cut out of bright construction paper, often with dazzling patterns as an overlay, such as in Breakthrough where a hand that appears covered with a skin of different colored eyes.

Alex Rubio, Burro Land, 1997...mixed media on paper 30 x 40 in...Collection of Henry R. Muñoz III, San Antonio, TX

Mark Hogensen adds to the three-dimensionality of kaleidoscopic space by cutting his geometric forms out of wood. Though the painted surface is flat, his angles and orbs seem to be shooting through different dimensions or floating in space. James Cobb, whose early work had a surrealistic edge, now uses a computer to create complex, multilayered prints that seem to merge organic forms with technological structure. Constance Lowe, inspired by the markings on butterfly wings, makes inkblots that resemble a Rorschach test, except that small discrepancies keep them from being perfectly symmetrical. Susie Rosmarin creates brightly colored, shimmering grids often inspired by gingham fabrics that appear to be descendents of the geometric abstractions of Anuszkiewicz and Julian Stanczak.

Two San Antonio artists have light-filled installations in separate galleries within the Cowden. George Cisneros, who recalls the psychedelic light shows he saw around the time of HemisFair in 1968, built a large-scale kaleidoscope, which he calls a “light show in a box,” that projects shifting, interlacing patterns on the wall. Richie Budd incorporates a bubble maker, snow machine, margarita maker, aromatherapy and a mixing board into a mobile DJ music machine, though the chief psychedelic effect is the mirror ball that pops up from time to time.

Michael Velliquette, Breakthrough, 2007...cut card stock and glue on paper 48 x 48 in...Collection of Guillermo Nicolas, San Antonio, TX

Videos are set up in the Great Hall. Ray Rapp updates Eadweard Muybridge, famous for his early photos of racehorses and runners in mid-stride, by using a series of small digital displays to show golfers, tennis players and other sports figures in action. Jeremy Blake pays homage to ‘60s Swinging London fashion designer Ossie Clark, featuring psychedelic abstractions and spoken words from Clark’s diaries. Psychedelic art has come a long way from the early rock concert light shows done with an overhead projector.

While “Psychedelic” presents a fairly solid survey of work by San Antonio artists, Austin is woefully absent considering how high it ranks with the state’s counterculture. There’s no scabrous sociopolitical painting by the late Peter Saul, although he is included in the catalog. And there’s no mention of Jim Franklin, whose posters for the Armadillo World Headquarters are hippie icons. And since SAMA strives to be an encyclopedic museum, it might have been nice to see examples of early precursors of psychedelic art, ranging from the peyote-inspired paintings of the Huichol Indians to Islamic art. Also, paisley is overlooked as a major influence on the psychedelic style. The drop-shaped pattern from India by way of Scotland became popular when the Beatles visited India, though its history as a symbol of youthful rebellion is much older.

Rubin makes a good case for psychedelia being an important current within contemporary art in the collectible catalog, Psychedelic: Optical and Visionary Art since the 1960s, published by SAMA in association with MIT Press. However, he uses a fairly broad definition that goes beyond drippy letters and floral patterns to include geometric abstractions, the sardonic realism of underground comics and the cosmic out-of-the-body visions of spiritual art.

Psychedelic: Optical and Visionary Art since the 1960s

San Antonio Museum of Art

March 13 – August 1, 2010

![]()

Dan R. Goddard is awriter living in San Antonio.

Also by Dan R. Goddard:

{ Review }

The Halff Collection at the McNay

{ Review }

Vincent Valdez at the Southwest School of Art & Craft

{ Review }

Contemporary Ceramics at Blue Star

{ Review }

"Reclaimed: Paintings from the Collection of Jacques Goudstikker" at theMcNay

{ Review }

Tom Slick: International Art Collector

{ Review }

"Lonely Are the Brave" at Blue Star

{ Feature }

San Antonio’s Museum Reach

{ Review }

Jonathan Monk at Artpace