Performance/Art at The Dallas Museum of Art is something of a welcome to the city’s new Performing Arts Center and Winspear Opera House. Organized by the DMA’s Charlie Wylie, the exhibition features work by six international contemporary artists riffing on aspects of the performing arts.

Un ballo in maschera (2004)

Yinka Shonibare

British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare’s Un ballo in maschera (A Masked Ball), a film based on Giuseppe Verdi‘s opera of the same title, is surprisingly intimate. Considering the combined spectacle of opera, a masked ball and Shonibare’s vibrant costumes, there is the potential here to swamp the viewer with intensity. But instead of orchestras and arias, one hears only the breath and footsteps of Shonibare’s performers—filmed from only inches away, we view it all as if standing in their midst.

Breath and footsteps are all we hear, that is, until a blast from a flintlock pistol in the hand of one hot assassin drops the King of Sweden, Gustav III. Both the opera and the film are based on his 1792 murder, but in A Masked Ball’s most compelling stylistic touch, Gustav rises like nothing happened, the action rewinds to loop again and history, or at least Shonibare’s version, repeats itself.

Shonibare often weaves his trademark Dutch wax print fabrics into a metaphor for the repeated failures of imperialism and so could seem to be playing a tired old tune. Here though, both tyrants and revolutionaries came to the dance, so everyone’s got blood on his hands.

The Eye (2008)

David Altmejd

Canadian sculptor David Altmejd’s dazzling installation The Eye was created in response to Doctor Atomic, John Adams’ 2005 opera about the psychological turmoil inside the creators of the first atomic bomb. Altmejd’s Eye is full of awe. Every surface a mirror, it fills the gallery with light, bathes the walls in refracted color and disorients the viewer. Commenting on his intentions, the artist said, “I see everything in terms of energy and nothing intellectually.” Altmejd claims even this explosion of reflective glass is more physics than psyche. “I tried hard not to make an illustration of the opera, but let myself be influenced by the graveness of the subject.” But, despite himself, Altmejd seems to be responding to Peter Sellars’ libretto for the opera (adapted from the Bhagavad Gita):

When I see you, Vishnu, omnipresent,

Shouldering the sky, in hues of rainbow,

With your mouths agape and flame-eyes staring—

All my peace is gone; my heart is troubled.1

Si bella e perduta (So Beautiful and Lost) (2009)

Frances Bagley and Tom Orr

The most ambitious installation of the show’s five acts, perhaps a little too ambitious by half, is by Dallas artists Frances Bagley and Tom Orr. They’ve recreated the quartet of concepts they designed for the Dallas Opera production of Verdi’s Nabucco, a work set in 6th century Jerusalem and Babylon.

A gobo lighting design and the reinterpretation in three dimensions of a painted backdrop for a scene in the Hanging Garden of Babylon both seem extraneous. Shoe-horned into their Quadrant gallery, they give it the feeling of a stagecraft sampler.

Much more successful are their reconstructions of the Euphrates riverbank and the idol of Baal, which might have made for a stronger presentation if they’d been the only ones there. Tall steel rods become reeds, and closely spaced stripes painted on the wall behind echo them to create a moiré effect: if the viewer moves his head, the reeds appear to rustle. Bagley’s Baal is one big squirrel—actually a digitally enlarged taxidermist’s form, hairless, earless and tailless. With its four legs spread, still having the wires intended for mounting to a display, it looms as a chilling specter; a stomping monster made more disconcerting by Orr’s mirrored, prismatically pretty light effects.

The House (Talo) (2002)

Eija-Liisa Ahtila

Finnish artist Eija-Liisa Ahtila based her three-channel video on interviews with women who experienced psychosis, but says that in all of her “human dramas,” the story is the thing.

I think the lady protests too much. For one thing, Ahtila envisions The House with a director’s attention to detail, with exact specifications for every gallery fixture from projection equipment to the color of drapes behind the screens.

In her video, Ahtila’s “Elisa” begins a soliloquy with precise descriptions: the exact layout of rooms in her summer house north of Helsinki, its orientation to the lush landscape outside and her quiet routine within.

Elisa’s detached delivery persists, even as things begin to slip out of control. “I think the living room of my house is breaking down,” she confides midway through. “It can’t keep things out anymore. My garden is coming into my living room.” Voices from a village miles away, her Volvo and a cow also make their way into the living room. Vividly conjuring a psychotic state the artist reveals, “I meet people. One at a time they step inside me and live inside me.”

Watching the creeping, engulfing cinematic style of The House, projected over three walls of the room, it’s easy to believe.

Paintings and works on paper

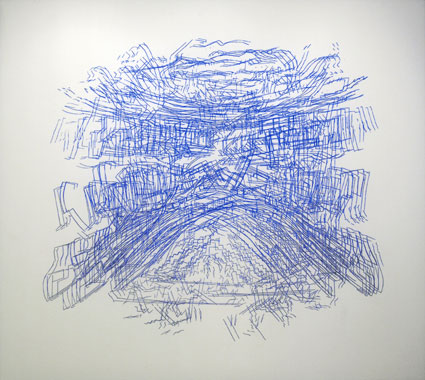

Guillermo Kuitca

“I still think that empty chairs are very powerful,” remarked Argentine artist Guillermo Kuitca while speaking at Southern Methodist University a few days before the Winspear premiere of both Verdi’s Otello and the stage curtain the artist designed for the opera house. Kuitca was attempting to sum up his affinity for alternative views of theatre: the dissolved seating charts, skewed floor plans and other myopic panoramas that activate his graphically informed works.

Kuitca is fascinated by places where action is either over or hasn’t yet begun; places where he senses a “fragmentation and dissolution” of energy, like the decaying notes that hang above the orchestra pit after tuning up. Kuitca has also detected and mapped it on another favorite resting place, the mattress; scene, he says, of the most important moments in life: our birth, our dreams, our sex and our death.

Kuitca’s work is not about upholstery, cartography or diagrams. There is a common thread that runs through it, made up of lots of little lines – blurred, vibrating and disintegrating – each resonating with human presence.

That human presence is what ties together the best work in this exhibition; work which, like the performing arts it references, shows evidence of life on what might sometimes seem to be an uninhabitable planet.

1. John Adams, Doctor Atomic, libretto by Peter Sellars drawn from original sources. (New York: Hendon Music, Inc., A Boosey & Hawkes Company, 2005)

Performance/Art

Dallas Museum of Art

October 8 – March 21, 2010

James Michael Starr is an assemblage and collage artist who lives in Dallas. He is represented there by Conduit Gallery and in Houston by Hooks-Epstein Galleries.

Also by James Michael Starr:

{ Review }

Susan Rothenberg at The Modern

Foster + Partners at the Nasher

Diego Rivera: The Cubist Portraits, 1913-1917 at the Meadows Museum