Dean Ruck and Dan Havel, two Houston-based artists, recently completed a two-part sculptural intervention called Give and Take. For the first part, the artists tackled a soon-to-be demolished house in the Houston Heights neighborhood, cutting out a single ovoid form from the center of the house. As the second part of the intervention, this form was dismantled, extracted, and precisely reconstructed in the main gallery of Houston’s Contemporary Arts Museum, where it is now on view. The project is a part of the CAMH’s current exhibition No Zoning: Artists Engage Houston. On view through October 4, the exhibition presents projects that mine the city of Houston. The artists sat down with Elliott Zooey Martin to discuss the project, its relationship to the history of architectural interventions and its particular relationship to Houston, a city in the cyclic throes of demolition and new construction.

Elliott Zooey Martin: Let’s start with the genesis of the project. How did it begin?

Havel: Toby Kamps had approached us, wanting us to do a big piece for No Zoning. With the opportunity of the CAM show, we needed a house.

Ruck: He was thinking of an on-site/off-site piece, that was tied to something outside of the Museum.

EZM: How did you find this property?

Havel: There’s a real estate blog, swamplot.com that posts the demolition permits. On Swamplot I posted that we were looking for a tear-down house of shiplap construction. We like to work with the sturdy structure of old houses. Two days later Larry Albert, an architecture professor from Rice University, responded to our posting.

Larry had bought the house in 2005 and had been holding on to it. The house was a wreck when Larry bought it from the owners. Eventually, no matter what happens, the house cannot be saved. That will be the first thing they’ll do: they’ll clear the lot. How they clear that lot, we’re not involved in that. Our piece is done.

Havel: Larry was gracious enough to give us the opportunity to do this, so we tried to be transparent from the beginning. We approached the Norhill neighborhood association to ostensibly get the OK to tear down the house. But also to let them know that we were going to do this. They were compelled and agreed that the house needed to be torn down.

Ruck: And a historic society subsequently agreed to that. So everyone was in agreement.

Havel: One of the parameters that we were handed by the neighborhood association is that they didn’t want a very public piece. They knew about Inversion. But they didn’t want their own Inversion. They didn’t want this huge social piece where they have a lot of people there. With that, our first idea was to completely take apart the house, move the whole house and put it together inside the CAM.

EZM: Would it even fit?

Ruck: It would!

Havel: So I built a rough scale model of the CAM and of the house. The house took about a third of the gallery space. But then we only had two months for the whole project, so we had to rethink it.

Ruck: We kicked around a lot of ideas, as we usually do. We went through different configurations of it and at some point decided we would excise an ovoid mass. From there we made a couple of models out of cardboard and transferred them into the house.

EZM: With this ovoid mass, the cut that comes to a point in the back two rooms, can you explain this?

Havel: The end of the egg.

Ruck: There’s a subtlety of our alignment of that egg within the house. It’s slightly off center of the axis. The center of the egg is somewhat tilted as opposed to directly down the center of the structure. Therefore, the end of that egg hits that wall off-center.

EZM: You cleared the house, conceptualized the form, and then drew it out and cut?

Ruck: Yes. Once the idea was there, it was a matter of executing it as best we could, and in a low-tech manner, in a certain time frame, without a budget.

EZM: What did you use to cut it out?

Ruck: Sawzalls.

EZM: Is the low-tech important to you? Do you try to match your tools to the original construction technology?

Ruck: No. Hand tools are about the extent of our technology. The form wasn’t digitized on a computer and then mapped out precisely.

Havel: We come to the site with what we’ve got. And yes we come with a generator and a tiger saw; but no, we don’t come with laser projectors that automatically give us a line. We found tool bits and parts of tools at the site that we actually used.

Ruck: Maybe that’s an aspect of it for me. I don’t like to be an over-consuming consumer. How much do you need? It’s about over-consumption. If the time we’re living in doesn’t make that very obvious, we’re seeing the correction in economy and society. And so, we’ve been pushed back a little bit. I think it’s a good, healthy thing. So, you know, use what’s available to you.

EZM: Do you map it out? And if so, how?

Ruck: We do. You can see white marks in certain places, from the plaster sheetrock. There was an endless supply; whenever you needed to draw, you just grabbed a piece and started sketching. We did do that on all the walls, trial and error. It was difficult since you cannot see through walls to try to visualize that next space.

EZM: Can we talk about the lack of basement? About the dirt floor beneath?

Havel: It tends to objectify the house a little bit. You get this house that you cut and drill into and it’s kind of presented on a pedestal. After we cut the floor out, we got to the dirt floor and realized that we had at least four more feet to go of really hard dirt.

Ruck: To finish the ovoid shape.

EZM: I’m surprised to learn that it was owned by someone else for the last three to four years.

Ruck: When we came into the house, it was full of the belongings of the previous owners.

EZM: The abandoned household items, where did they go?

Ruck: At first, the owner cleared a fair amount of it. And then there were just bags of odds and ends. Every week we filled the house dumpster. Eventually we cleared it so that we had room to work.

EZM: Did you have to clear it first before you could conceptualize the form?

Havel: Yes. We needed things moved out of the way so that we could cut.

Ruck: So that we could cut, but I think we conceived the piece before the house was cleared.

Havel: We did a larger-scale piece than we had earlier envisioned. It was scaled down from cutting it from edge to edge of the house.

EZM: Had you wanted to cut it from boundary to boundary?

Ruck: We had that idea of having the end hitting the back wall and the front wall so that you could see from outside

EZM: I liked the opportunity to walk around the hole and explore the piece.

Havel: Part of these projects has to do with the labor required. We had ideas of cutting straight through the clothes hanging in the closet. But it involves some trickery with gravity, hanging a rod that we would have had to cut. And I think one of the things that Dean and I have in common is: it is what it is.

Ruck: There’s a certain purity or one-mindedness to the idea. People bring their own context to it. It’s a little overwhelming how focused people are on, not the form, not the cuts, not what we did, but the history of the house.

EZM: Well, part of that has to do with the relics. I realize that you went to great pains to clear the house; but there are still a wide variety of objects left in the house.

Ruck: We didn’t take too much pain to clean the place. We needed to get things out of our path for construction or deconstruction. Other than that, it is what it is. We were certainly fascinated by the history, too. And we sort of mined through that. But it was the back-story and we weren’t focused on it.

EZM: I was interested in Larry Albert’s acquisition of the house.

Ruck: As far as we know, he bought the house directly from the family of the occupants. And a bit of the back-story that we pieced together is that a brother and sister lived there. And they were both aging, she was on a mental decline, he on a physical decline. When the brother died, the family moved the sister out and put the house on the market and Larry bought it.

Havel: So they lived a very sad existence in this broken down house. But then once it was bought, it was kind of sealed and preserved.

EZM: And what about the larger context of the house?

Havel: I like this idea of working in that grey area when it comes to art, presenting art, in the museum, outside the museum, in between the museum and the public, and playing with that whole dialogue of where it’s presented. I like the fact that these pieces are presented in the middle of a neighborhood that really doesn’t know what’s going on.

Ruck: Right. Never had a piece of art in it, other than a painting over the couch.

EZM: Have you spoken with the neighbors?

Havel: The neighbors aren’t against it. People are very aware of what we’re doing, what we did.

Ruck: They’ve all been in to see it, on numerous occasions.

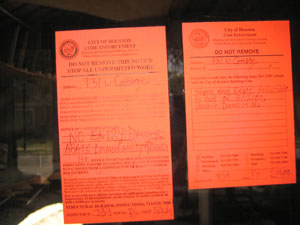

EZM: Can you explain the red stickers on the doors?

Ruck: This is really just token bureaucratic infiltration. The City had to do something. Some permit inspector had to come over.

Havel: There were no fines that we know of. Either a neighbor called the city or Larry triggered the inspection by pulling a demolition permit. The inspector came by the house, peeked in the window, and instantly saw the hole.

EZM: So the stickers were posted after you had started cutting?

Havel: When we got it all installed at the CAM, we got tagged.

EZM: How long will the house stay up? Does it come down at the end of No Zoning?

Ruck: I think it’s whenever the owner gets around to it and/or if he’s pushed by the city. It’s red tagged as a dangerous building and he has a responsibility to deal with it.

EZM: The other part of this project is the sculpture at the CAMH. Did you construct it in the galleries?

Havel: Yes, it came apart. We would cut pieces, filling the house’s back rooms. We finished it two weeks before we needed to move it in the CAM. With their support we had a crew and a flatbed truck so we could move the 22-24 pieces in one run. So you’re deconstructing a ship in a bottle and reconstructing a ship in a bottle.

EZM: Can you talk about that relationship between this performative operation and the static object in the gallery space? Do you see these as two separate but interrelated events?

Ruck: Maybe. We knew it would be these two different locations, related but separate. And they are very distinctly different things. I think the piece at the CAM is more of a marker for the house, for the negative space. The positive is sort of a marker for this negative.

EZM: It’s not a pure indexical trace. It’s reconstructed. At the same time, at the house you see that the site is not just a means to an end.

Ruck: Let’s consider the positive part at the CAM. I hope it’s not viewed too much as a construction, rather the displacement of one form into another place. We tried to reconstruct it so that it wasn’t obvious that it was torn down and rebuilt.

Havel: The idea of having two different pieces going on consecutively is something that intrigues me. There is no way that you physically can be at both places at the same time. So there’s always this game you’re going to have to play with the two pieces.

Ruck: It’s a mental game, but it’s a physical game too.

EZM: You certainly work within the lineage of Gordon Matta-Clark‘s "anarchitecture." Can you elaborate on this relationship?

Havel: I didn’t know anything about Matta-Clark until after graduate school. He is one influence out of many. I think assemblage better characterizes my practice.

EZM: It’s interesting that you worked with the neighborhood association. In my opinion Gordon Matta-Clark had little care for the actual inhabitants of the neighborhoods he worked in.

Ruck: I feel like my work is very much based out of the seventies. But I certainly haven’t spent a lot of time studying Matta-Clark.

Havel: I don’t approach my art with a social agenda. I don’t want to open up a restaurant called "Food." Matta-Clark asked questions that people are still talking about. And he’s among many, many people that Dean and I have been influenced by. But when it comes to the zone, when you’re thinking about an idea, all those people drop far behind. I’m not thinking about any of those guys. I may make those associations later.

EZM: A lot of your work seems to employ circular forms – Inversion was a funnel, Apartment Suite was a circle, Give and Take is ovoid. Can you talk about that?

Ruck: I think we lean towards universal forms. Maybe it’s something of a common denominator because we’re obviously two different people with different ideas. And you have to come to something.

Havel: I’m not wed to the organic. My thoughts go both ways. When it comes to choosing an organic form in a given architectural site, the site has a given geometry. It is a grid.

EZM: And you then respond to it?

Havel: Well, I’m more comfortable responding to it in a more confrontational way, organically. Interject some new form into what’s already there.

Ruck: As a contrast.

Havel: Right. It opens up new visuals of what you perceive and what is happening in that grid system. People aren’t used to walking into an organic architectural space.

In the end, we exposed that house. And I think that transformation of a space through some sort of physical action, tweaks with one’s experience of walking through space. We’re just doing some house renovations before the house gets torn down.

Ruck: I think that’s part of the euthanasia of the project. This is the house’s last stand; its last hurrah.

EZM: There’s impermanence to the built world. But in the context of Houston, there’s a hyper-impermanence. Is this context a catalyst? Does this inform your practice?

Havel: We’re both preservationists. I understand that a built site has an inherent soul or memory. It’s fun to play with that dialogue about houses disappearing. We’re interjecting ourselves in that dialogue, at a point where the house is going to go away and we’re going to give it another chapter.

Ruck: I think there’s a bit of an applied context, one applied by others. Certainly, we have a sensibility. And I consider myself a preservationist. But the context of that being, the cue or key to the work is not in the forefront of our thinking. For me, it’s more a matter of process.

As a formal approach, it’s a three-dimensional formal exercise as a means to a process which is more an element of the work than the context of the Houston environment of tearing things down. We’re fortunate that there’s plenty of medium and material here. I think it’s got to be something behind our thinking. But it’s not on the forefront.

EZM: It’s a part of our daily life. There’s a shock to the rapid changes in the built environment of Houston.

Ruck: It’s pronounced and unfortunate.

Havel: I like any opportunity where I can make art in the path of an unaware public. It’s fun to play with that element of surprise. We’re not really about architecture. It’s more about space, altering space and taking spatial relationships and tweaking it slightly and hopefully getting the audience involved or not. Salvage is closest to what we do. We salvage. One of the things I want to make sure that we don’t get pigeonholed is that we deal with only architecture. It is very project-based. And really what the project brings to it, it doesn’t need to be based on a condemned house.

I think there’s a self discovery that happens that I’m much more interested in than telling everybody the answers. We’re just asking the questions-what if? What if we do this?

EZM: So, what is the question for Give and Take?

Havel: What if we cut a huge chunk out of the interior of this house? Would it fall over? What if?

Ruck: Or, if you cut an exterior piece out of a different house, how does that change your impression, your perspective, your thought about that particular house, the neighborhood, the context of Houston… It’s a pretty simple gesture. It doesn’t take a lot to raise the question. It’s the answer that’s complicated, not the question.

Elliott Zooey Martin is the Curatorial Assistant for Contemporary Art & Special Projects at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

Also by Elliott Zooey Martin:

Interview with Trenton Doyle Hancock: "Cult of Color"

2 comments

Brilliant. Houston is a lucky city to you two guys.

Unsatisfying, dismissive and ultimately evasive answers to the Gordon Matta-Clark questions does not bode well for either of these building hacks.