I went to my cardiologist the other day and, like many times before, she put a small receiver over the raised square area above my heart and waited for a computer to read the stored data from my pacemaker-defibrillator. This time it made a sound it doesn’t usually make. As my doctor looked at the computer screen she nodded her head.

“Yep. I thought so. Your battery’s dead.”

“It’s completely dead?”

“No, it needs to be replaced within a month.”

It’s not the first time and it won’t be the last time that I will have to give up my citizenship in, as Susan Sontag wrote in Illness as Metaphor, “the kingdom of the well,” and dust off my passport for the “kingdom of the sick” to go to the hospital for four or five days. Four years ago in a classroom at the University of Houston, as I was looking at a slide of a Clyfford Still painting my heart began to race. I tapped my friend Veronica on the shoulder and asked her to follow me out of the class. As I headed for the door and put my hand out toward the handle, my vision closed in, shrank to a pinpoint and disappeared.

I woke up a few minutes later outside the classroom on the ground. Veronica had caught me as I fell backward, dragged me through the door, and laid me on the ground. She was yelling for help as I opened my eyes. My heart had begun beating so fast that it began to quiver and stopped. Ventricular fibrillation and subsequent cardiac arrest results in death nine times out of ten. It’s what killed my father. I’ve died twice before. During my senior year in high school I had my aortic valve replaced with a stainless steel version and, still unconscious in intensive care, my heart stopped twice. Both times the doctors had to revive me with defibrillator paddles ER-style.

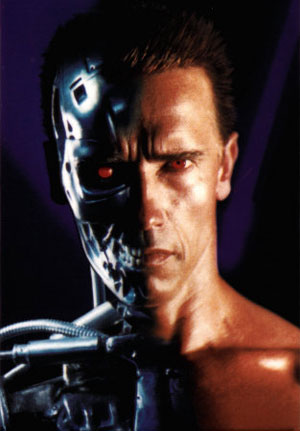

At the hospital, after my heart stopped this most recent time, my doctor told me I would need a pacemaker to keep the arrhythmia from happening again and a defibrillator just in case it did. On October 15, the fifth anniversary of my dad’s death, I became an embodiment of the metaphorical creature from Donna Haraway’s A Cyborg Manifesto. My pacemaker and the half dozen medications I take treat the symptoms of my heart disease, but do nothing to change the fact that it’s likely I may die before my mother. Almost wholly dependent on a battery to keep my heart beating, in the middle of my last year in graduate school I entered a new world as an artist.

Since that time four years ago, I’ve refused more and more to buy stock in the commodity of cultural materialism. Through my experiences of being subjected to one of the greatest power structures known to humanity – medical science – I’ve come to believe that technology, gender, race, sexuality and class have less to do with our humanity than the last 30 years of cultural study would have us believe. Having become inextricably entangled with the financial and political structures of medical science, I have nonetheless refused to let those structures change my perception of myself as a flesh-and-blood human being, unique and irreducible even in my physical dependence on the rhizomatic technology that gave birth to the computer in my chest.

Technology invades and supplements all of our lives in an infinite number of ways. We’re all under social and technological pressure from without, and sometimes, like myself, from within. The child who plays six hours of Wii every day and Cory Archangel, who makes art about the technology that child has become integrated with, are all cyborgs. I suppose if your physical life has ever been affected by interaction with media – if you’ve ever gone to an appointment that was confirmed through e-mail, for example – you’re a cyborg too. The important question is: does this fundamentally change who we fleshy creatures really are?

The world of cultural production, of which the artworld is arguably the most elite tier, has lately been busy creating a pseudo-science around the idea that our identity as human beings is truly changing – that the relentless churn of a constantly amplified capitalism, the birth of the internet and the myriad systems of production they have made possible have done something to irreversibly change our relationship to space and time.

Curators and art writers have very successfully co-opted Deleuze and Guattari’s notion of the “body without organs” to describe contemporary art practice. This idea consists of the assertion that bodies of all kinds are comprised of fluid interactions between genetic material, language systems and technology. In this way, entities that have traditionally been thought of as more or less stable and acted upon by outside forces, are thought of as moments in a continually active, unstable flow of material and information. You, sitting in front of your computer screen reading this, are a moment in a flow of information and material that is ever-reducible or ever-expandable. Think of yourself as a snapshot of a particular interaction between genetic material, culturally produced language and politically constructed technology.

In this system of belief, every bit as metaphysical as the idea that Jesus rose from the dead, the bee is nothing without the flower and I am nothing without my pacemaker. As I sit here nervously awaiting my doctor’s call to tell me when I’ve been scheduled to go under the knife, I refuse to believe that I’m nothing without the pacemaker or the valve, that I am no more than the sum of the forces that have acted together to produce me.

So what do I believe and how do my beliefs inform my artmaking? Do I believe in the Christian or Islamic God, the Hindu pantheon or the trusty bogeyman of the contemporary artworld, the linear “Modernist project”? I hardly know what the terms mean anymore. I don’t believe in the way they’re usually characterized by curators like Shamim Momin in her catalogue essay for last year’s Whitney Biennial or Nicholas Bourriaud, the writer and curator who coined the phrase “relational aesthetics,” and has successfully built a system of thinking about art that deals with the intricacies of the types of social and material interactions that Deleuze and Guattari describe. The question for me has become, how does a politically liberal, atheist artist in love with formalism defend the notion of the author and the idea that there is something intangible and mysterious about being human and making art?

I haven’t figured it out. The truth is that the only thing I really believe in is life. I want to live. I hate death. I want to live forever and I know that I won’t. And that’s what makes me a human being. So for the next week or so while I sit in a hospital bed, chest and balls shaved, enjoying a morphine drip, I’ll leave you with the words of a better artist than myself:

I did my best, it wasn’t much

I couldn’t feel, so I tried to touch

I’ve told the truth, I didn’t come to fool you

And even though

It all went wrong

I’ll stand before the Lord of Song

With nothing on my tongue but Hallelujah

– Leonard Cohen, from “Hallelujah”

Michael Bise is an artist living in Houston.

3 comments

I just thought you might like this piece: http://www.nytimes.com/2009/04/26/magazine/26zen-t.html?pagewanted=1

Inspiring piece Michael,

Wow, I was just lying on my bed, in pain because my leg hurts–a little, thinking that I should have finished my laundry before my leg crapped out on me. Now I can’t. I read Cyborg, and got out of bed and am pushing through the “pain” Thanks for the perspective on pain.

P.S., I say put a little faith in the bogeyman to mix it up a little !!

Keep making your art!! we need it in our lives

Everett, I love the photograph…

My husband, nicknamed ‘Iron Jim’ has been through 2 multiple bypasses, a stroke, is on his 3rd pacemaker, has a shunt running from his brain into his belly to relieve pressure from a slow-growing tumor, has had an aneurism tied off, and has made it to 67 and does appropriate exercise at a local gym.