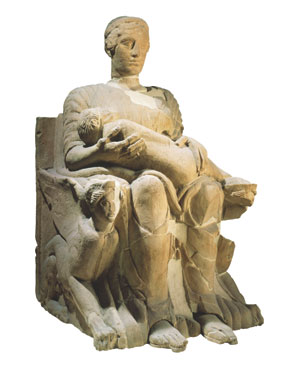

Mater Matuta...Third quarter of the 5th century B.C.E.,Stone...Florence, National Archaeological Museum

From the Temple and the Tomb: Etruscan Treasures from Tuscany at the Meadows Museum at Southern Methodist University honors the 15th anniversary of SMU professor P. Gregory Warden’s landmark archaeological excavation in Poggio Colla, Italy. Exhibiting more than 300 objects from the 9th to 2nd centuries B.C.E. from the National Museums of Archaeology in Florence and Siena, it is the most thorough survey of Etruscan art presented in America to date. As a part of the current series of Dallas exhibitions focusing on ancient civilizations of the Mediterranean, this is a much better bet than the over-hyped King Tut show at the Dallas Museum of Art.

To many of you (myself included), Etruscan art is a foggy memory from a Roman art history class taken years ago. This exhibition recalls the inventiveness of this influential yet enigmatic civilization while serving up a slice of Etruscan life as best as possible. Predating the Romans, the Etruscans lived in the Italian peninsula from approximately the 9th to 2nd centuries B.C.E. and were influenced by the near East and Greece. The origins of this civilization are still unknown, but we do know that the Etruscans were militaristic and agrarian, possessed polytheistic religious beliefs and had a unique language that is still being decoded. Those few primary written records that remain are chiefly Etruscan temple and funerary inscriptions. In fact, most of what is known about the civilization—and most of what is included in the exhibition—comes from surviving temples and well-preserved monumental tombs.

While tombs were created for people of all social classes, the large-scale tombs of the social elite provide the most information, as they included a larger number of artifacts. With complex and evocative domestic interiors, the tombs of the elite were often elaborately decorated with murals. They contained funerary urns, or sarcophagi, which housed the ashes of the dead, paired with the deceased’s prized material possessions, including militaristic and utilitarian items such as safety pins and decanters. This suggests that, like the Egyptians, the Etruscans believed that the soul and body were forever intertwined, and that such possessions accompanied the dead (and asserted their status) well into the afterlife.

Organized in a clear chronological order, the exhibition explores the history of the Etruscans through the evolving contents of their tombs. Displayed in a series of deep shadow boxes along corridors bordering the main gallery space, the objects offer glimpses into the everyday life and developments of this civilization as well as their influences. The first section, Origins of the Etruscan Civilization (9th to late-8th century B.C.E.), presents funerary objects from the Villanovans (named after a town near Bologna). Many of the clay funerary urns from the late-9th century B.C.E. were fashioned after the one-room domestic huts of this period, further suggesting the belief that such domestic trappings transcended into the afterlife. Relatively unadorned, black clay vessels, such as amphorae, are representative of this period and are a marked contrast to the elaborately painted pottery seen in later periods.

The following section, Princely Culture (late-8th century to mid-6th century B.C.E.), evidences a shift in funerary objects from the simple to the luxurious, as well as an Oriental influence on artistic production. As the wall text explains, during this period the Etruscans asserted their power and status in the merchant and trade worlds. With increasing trade and the subsequent assimilation of outside cultural influences, many of the luxury goods presented here are either from or influenced by the near East. The elite segment of society seems to have especially prospered during this period, with intricate gold funerary jewelry taking precedence over the uncomplicated clay objects found in the Villanovan tombs. Militaristic objects also appear, including an elegantly elongated bronze trident, but these unscathed and embellished objects appear purely symbolic and decorative.

The Urban Society period of the Etruscan civilization (end of 7th century to 4th century B.C.E.) demonstrates the development of well-organized city centers, a rising middle class and a further increase in trade. During this time, new-and-improved methods of mining metals were developed, resulting in intricately crafted bronzes—such as an assortment of finely made, albeit smashed, helmets presumably used in combat.

Helmet...Middle of the 7th century B.C.E., Bronze...From De Populonia, Necrópolis della Porcareccia...Tomb of the Bronze Fans Florence...National Archaeological Museum.

Increased trade with Greek merchants introduced different types of ceramics as well as liquid goods, such as oils and wine, to the region. As a reflection of this, Greek-inspired red-figure pottery pieces, along with chalices and vessels, dominate the Urban Society section. Here, figurative urns also replace the earlier hut-shaped urns. Male Canopic Urn, impasto, late-7th century B.C.E., found in the town of Cetona, depicts a stylized male head with a rounded body for its base. These figurative urns were stylized forerunners to the veristic Etruscan sculptures and sarcophagi seen in later periods and also in Roman civilization.

The final section of funerary objects, the Hellenistic Period (4th to 2nd centuries B.C.E.), represents the last fruitful centuries before the Etruscans were completely sacked by the Romans. Here, even the most quotidian objects are beautifully crafted and imbued with a sense of significance. For example, Fire Poker, bronze, mid-5th century B.C.E. Populonia, is an elegantly curved hand on the end of a Doric-looking column. These household objects are decorated in a rather fantastical manner, such as golden safety pins marked with flourishes and slender candelabras adorned with small ducks. Several of the delicately painted ceramics exhibit a sense of playfulness, such as Duck Askos, late-4th century B.C.E., an endearing bird-shaped decanter. Most of the metal objects, such as the handheld mirrors, are engraved with images that have an elegantly stylized simplicity somewhat akin to the drawings of Aubrey Beardsley. Although the exhibition asserts an industrialized approach to the objects of this period, the embellishments and sculptural progressions seem to contradict this assessment.

Monumental sculptures found in both Etruscan tombs and temples fill the main gallery. A large temple pediment from mid-2nd century B.C.E. Talamore frames the large room and illustrates the Greek mythological tale of Oedipus and his sons. The animated figure of the blind Oedipus is flanked by the bodies of his two sons, Eteocles and Polynices, who have just killed each other in a power struggle. Installed below the pediment is the large and elaborate urn of Larth Cumersa, from late-3rd century Sarteano, which also depicts this battle. The scene is executed in high-relief on the urn’s front panel. The juxtaposition of these two pieces demonstrates the Etruscan assimilation of Greek culture in both religious and funerary contexts. Also displayed in the main gallery are incredibly detailed sarcophagi featuring reclining figures that, when seen as a group, exhibit an idealized similarity in pose and overall build. This is, perhaps, illustrative of the industrialized approach of the Hellenistic period mentioned in the wall text. However, the unique facial features seen in many of these sarcophagi demonstrate a growing interest in veristic portraiture, which was further developed by the Romans.

Etruscan art has frequently been viewed as unimportant within the canon of art history. Often characterized as primitive, it has served primarily as a convenient placeholder between Greek and Roman art. However, From the Temple and the Tomb: Etruscan Treasures from Tuscany effectively turns this centuries-old preconception on its ear by clearly demonstrating the inventiveness and distinctiveness of Etruscan artistic production.

From the Temple and the Tomb: Etruscan Treasures from Tuscany

January 25 – May 17, 2009

The Meadows Museum, Dallas

Alison Hearst is an art historian and writer living in Fort Worth.

Also by Alison Hearst –

{ Review }

"Uncommon Sense" at Fort Worth Contemporary Arts

{ Review }

Lawrence and Havel at Dunn and Brown Contemporary