The work in Sehnsucht (Aspiration), currently showing at Light & Sie Gallery in Dallas, is at once challenging and accessible; vaguely inscrutable in its occasional abstraction and seemingly easy in its hung-on-the-wall two dimensionality. Gagosian Curator Georges Armaos took the title of the show, Sehnsucht, from the lore and practice of German Romanticism, a turn of the eighteenth century movement in poetry and literature. There is no exact translation of the German word “sehnsucht” into English, but its meaning and translation hover somewhere around the ideas of “aspiration” and “longing.” The word is like “drang” in Sturm und Drang, a related German movement in letters that roughly translates into “storm and stress,” “storm and impulse” and even as far off as “passion and energy” and “energy and rebellion.” The ambiguity of the title Sehnsucht (Aspiration) coalesces in convincing if not subtle fashion in the ambiguous nature of the work in the show.

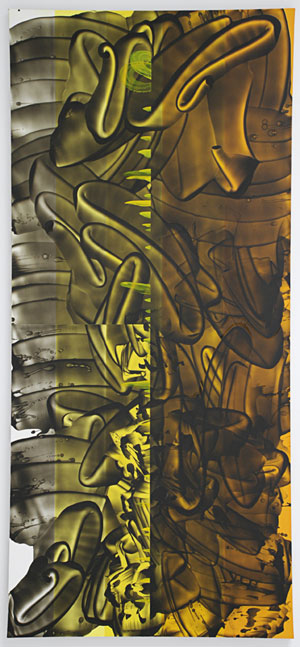

Two paintings by American David Reed, #570 and #571, hang at the head of the large, luminescent white room that is Light & Sie Gallery. At a little over 9’ x 4’, they are long, tall and magnificent. At first, seen from afar, they seem like simple gestural paintings with a striking sense of monumentality. Gestures come in swirls of grey-black watery paint atop bright, fluorescent surfaces. Stand back and the heroic Ab-Ex gestures give way to the anonymity of an electronic screen. In the bright color beneath the brushstrokes, Reed references the lunar glow of the object in front of us all, the screen before which so many of us genuflect on a minute-by-minute basis. Up close, the surfaces are almost wax-like. They are confusing as they seem to be covered in encaustic and printed from a copy machine at the same time. They are made from oil and alkyd, resin-based paint used to cover high traffic areas in homes, such as doors, cabinets and trim. Reed makes the paintings in layers over several years, smoothing each stratum with a sander. Dated 2005-2007, these paintings took two years to make. The results are tight surfaces that are simultaneously opaque and translucent.

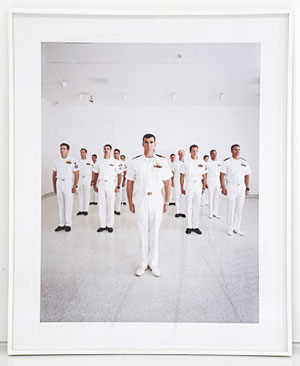

Gender-suggestive works by Italian Vanessa Beecroft and American Jeremy Kost hang on an adjacent wall. The four photographic pieces are collectively driven more by content rather than formalism, but they are nonetheless ambiguous like Reed’s work. Beecroft gives white-on-white new meaning, transgressing through figures the way Robert Ryman does stretchers and Kirsten Macy does perspective and explosions. In VB 39, US Navy Seals, Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego and VB 39, US Navy Seals, Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego, Beecroft has photographed a small phalanx of service men, who are dressed in crisp white uniforms standing in the hollow white box of the Farris Gallery at the Museum of Contemporary Art in San Diego . The photographs document a one-time performance in which Navy Seals stood rigid and still for an hour and a half. Adding white to white-on-white, the men are all Caucasian. What’s less clear is their sexual orientation. As we all know, but don’t ask and don’t tell, is that if you are a man or a woman and looking for hot, beefy men in good shape, then you join the service. The man up front with the carefully disciplined bushy mustache is especially suggestive of the leather daddy or cowboy in the Village People.

Jeremy Kost’s Simon and Marshall are less successful than Beecroft’s photographs. By comparison, Kost’s framed grids of pornographic, nudie polaroids are slap-dash and cliché. Simon shows 72 shots of a pretty blonde boy in white briefs smoking a cigarette, with Barbies of all persuasions in his crotch. Sometimes he’s in the picture with a hard-on under his tighty-whities and sometimes just Barbies are all camped out in campy fashion. The photos of Simon are washed out, while those of Marshall in the eponymously titled Marshall are dappled in sunlight and shadow. 56 polaroids show Marshal going from shirted to shirtless to naked with a raging erection. Youthful prowess here does little more than recall Andy in bastardized fashion.

Seen from the Archimedean point of Curator Armaos’s overarching theme, "Sehnsucht," the gender-suggestive work of Beecroft and Kost is right in keeping with the ambivalent form present elsewhere in the show. Kost’s nudie gay-fest goes seamlessly with Beecroft’s distillation of would-be closeted gayness, both of which connect gracefully to the formal ambiguity at work in Reed’s paintings, all of which brings us back to the ambivalence at work in the very idea of the Romantic. Though the gender-bending tendencies of German Romanticism are not of central concern to scholars, it nonetheless remains present in the texts. One example that makes the long ago seem not so long ago is an early novelette by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, The Sorrows of Young Werther. Werther self-destructs from hard swooning over unrequited love. He commits suicide over Lotte, who spurns him for an older man whom she married. The daintiness of this tale is in Werther’s effete emotionalism, a force meant to counter the rationalism of the Enlightenment that is often stereotyped as female in nature, and his dandy sense of fashion. Not only did the novel trigger copycat suicides across the city-states that would one day be Germany, but Werther’s English fashion sense, especially his yellow leather knee-britches, became all the rage. How recherché. How longed after, as in “longing,” or Sehnsucht.

The themes of unresolved form and mystifying sexuality continue into the smaller gallery, which feature two moving-image works: Korean Kimsooja’s single-channel video, An Album: Havana and French-Israeli Joseph Dadoune’s 16 mm Sion. Accompanied by four giclée stills, Kimsooja’s An Album: Havana is a seven-minute view that unfurls from a moving vehicle. The artist interrogates the limits of vision — the milky-gray view of barely discernible figures suggests severely impaired eyesight. Filmed at the Louvre, Dadoune’s Sion shows Israeli actress Ronit Elkabetz clad in wraith-like and baroque regalia roaming around the halls of the old French palace turned public museum in central Paris. As the allegorical figure of Jerusalem, Elkabetz is both queen and goddess, tortured in her power and trapped in the dead-zone of a museum where she finds no representation. One assumes the implication here to be something about the imperialism of the museum, East meets West and the artist’s childhood in Nice as opposed to adolescence and adulthood in the Middle East. Elkabetz’s billowing garb is arresting, as is her statuesque beauty, but the black and white 16 mm film is nostalgic. It creates a false sense of gravitas that is all too cloying.

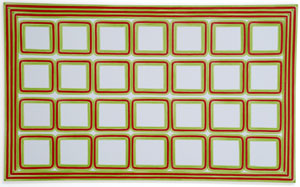

If you’re interested in the hung well, then you’ll really like the way American Dan Walsh’s Premier, a delectably washed out neo-neo-geo painting, is hung on the wall. Hung low, only so many inches from the ground, it is a green and red grid of 28 squares. Ingrid Calme’s #112 Working Drawing elides topographical representation into graffiti. This large color pencil on trace mylar piece is, not unlike the paintings by Reed, at once about tops and bottoms, surfaces and depth. One looks through the mylar layers, reading colored lines and striations at each level.

It’s one thing to bring out the common qualities of a disparate body of work, as Curator Armaos has done in Sehnsucht (Aspiration). It takes a keen eye and it has been done. What makes this show so powerful is that it is an idea — the German Romanticist notion of “longing” — that makes the connection here so convincing. Here’s to a brilliant show in the stellar space of Light & Sie Gallery — a broad open gallery that makes a girl want to nudge knuckles and bare ass in a perverse performance of roller derby.

Sehnsucht (Aspiration)

July 31 – September 6, 2008

Light & Sie Gallery

Dallas, Texas

Charissa N. Terranova is the Assistant Professor of Aesthetic Studies

at UTD and the director of Centraltrak, the UTD Artists Residency Program.

Also by Charissa N. Terranova

{ Feature }

Punkish and Puckish: An Interview with Tim Noble and Sue Webster

{ Feature }

Arthouse Renovation

{ Feature }

Becoming-Animal: Rebecca Carter, A Hybrid Approach to Art as Life

{ Interview }

Tracey Emin is a woman’s woman