July 16, 1969...Neil A. Armstrong, Edwin E. Aldrin Jr., Michael Collins...© On Kawara, courtesy of the artist and...David Zwirner, New York

A lifetime: what does it amount to? The body moves here, the body moves there, it encounters other bodies, perhaps even producing a couple more. Years scroll by and fin, exit, stage left. Sure, maybe those motions are spectacular enough to land you a one-hour stint on the Biography Channel (where it seems to help if you’ve committed some heinous acts, be they murderous or musical). But isn’t most of that just whistling past the graveyard? Doesn’t so much of what passes for memoir end up reducing the impenetrable mystery of our true nature to just so many facts, and dramas diminished by interpretation?

I get a little queasy when I hear those tributes in the media to fallen heroes, whether at the World Trade Center, or recently blown up in Iraq, or crushed by a drunk driver heading home on I-35. Loving father, mother, brother, spouse; funny, sweet, courageous, loving. Aren’t we all really so much more – and so much less?

On Kawara has now spent over 40 years documenting the brutally/poetically mundane base parameters of life on earth, meat-body bound. A selection of his work is on view at the Dallas Museum of Art, in On Kawara: 10 Tableaux and 16,952 Pages.

Kawara’s I Met 1968-1979 is a series of black volumes distinguished from each other only by the year, in silver numbers, on their spines. Their pages simply list the people the artist encountered each day – sometimes it’s just the same individual for an entire week. Lover, spouse, cellmate? Questions arise but remain unanswerable. Occasionally, you come across a recognizable art world luminary, but mostly, these are strangers to us, blank indicators of personal connections that remain unexplained and unknown.

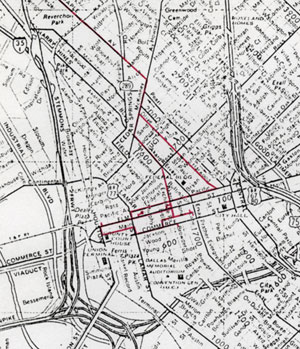

On Kawara...I Went 'Dallas,' 1968–79...binders, ink on printed paper, and plastic sleeves...collection of the artist, courtesy of the artist and...David Zwirner, New York...photo courtesy of David Zwirner

Similar annual tomes, titled I Went, are filled with red-inked maps, one for each day, showing the methodical movements of a being traversing a city’s labyrinth; the planet’s surface. Trips to the post office, the store, a gallery, or often enough, nowhere at all – just a static dot on a page, presumably indicating an artist hard at work, making maps and books.

Kawara has produced one of the most convincing and consistent testaments to the conceptual art revolution of the 1960s, but he made a smart, early decision to maintain a conversation with the historical language of painting. That production is now documented on one small, framed calendar chart, showing every year of his life and then some. A green ink dot indicates if a painting was completed; a red one signifies if it was bigger than the average; yellow simply shows if the artist managed to just survive another 24 hours.

Begun in 1966, the paintings tersely record the date in an unchanging font and format, and have become the artist’s signature works. Early on, Kawara made them every day, but the calendar reveals the eventual ebb and flow of their production. As easy as it would make it to just silkscreen them, Kawara instead crafts each by hand in a laborious day-long process.

Composed simply of a few numbers, some letters, a canvas and some

paint, they nonetheless bear a marked, if oblique, relationship to the

landscape tradition (both Asian and European), but allude to vistas more

esoteric than terrestrial, remaining retinal in only the most

utilitarian way.

July 21, 1969...Apollo 11 at the Distance of 238,857 Miles...from the Earth...© On Kawara, courtesy of the artist and...David Zwirner, New York

Kawara is apparently a newspaper junkie. Selected leftovers are boxed and labeled, silhouetting the individual against a background of dramatic happenstance. Humanity’s tragedies and triumphs aren’t editorialized upon, not in a way we can clearly discern – except in their re-presentation. Kawara’s emphasis on certain dates, specified by the increased scale of some paintings, is sometimes clear – like on the day of the first lunar landing, paired here with dramatic newspaper headlines – but the significance of other days remains unfathomable.

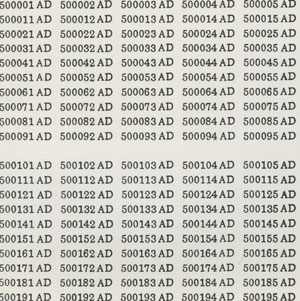

These human-scaled histories are drops in the proverbial ocean of Kawara’s catalogued eons. A million years BC fill five volumes, a million years AD fill another five. Years are listed individually, column after column, page after page, book after book, coolly laid out in glass cases, reinforcing an eerie objectivity. What was going on in year 368,937 BC? You’re left absurdly considering the specificities of a year in the life of a wooly mammoth, or of some hairy hominid predecessor walking a savannah far away in time and space. And where will humanity be in 237,635 AD? It all helps keep your home foreclosure in some kind of proper context.

Kawara’s operation is essentially a series of these perspective-altering mechanisms, generating questions from the cosmic to the intimately personal. Kawara mostly documents his own life but, because he reveals nothing of his internal experience, it all points directly at you. What would the map of my day look like? What was I doing that particular year? Am I any more than the objective markers of my passage through time and space? Meanwhile, the percentage of us born after the earliest of his date paintings increases, and death will find us all long before his art stops addressing the earth’s rotation around the sun. Time is against us. In Kawara’s boundary-less art, we all become bit players in a universal theater; sand in his hourglass.

The One Million Years Project (detail)...© On Kawara, courtesy of the artist and...David Zwirner, New York

It’s staggering to imagine Kawara setting up the basic parameters of his artistic inquiry more than 40 years ago and working within them since, maintaining this kind of fetishistic intensity. This is the genius of his achievement. It’s reminiscent of the Mayan Day Keepers, who believe their calendrical rituals keep the world itself spinning; or the Hopi, who believe their precisely scheduled dances keep the desert rains coming and the sun on its track. I doubt Kawara has such a grandiose faith. But if finding meaning is the bedrock of existential satisfaction, the artist’s dedication to this austerely minimal program paradoxically indicates complex webs of connection, and underscores the intrinsic richness of the very act of being. Even the most useless of days is worth attending to and documenting – and even the most dramatic will slide quickly past in the endless stream. Life’s a killer, and time the great equalizer.

What am I? What constitutes the self? What does it all amount to? Much of what we witness in the news and in the tumult of our daily lives are simply symptoms of the fitful ways in which humans go about trying to seek answers to these kinds of questions. Kawara confronts us with fundamental issues, devoid of didactic threads of interpretation. Stripped clean from any conventional idea of expression, narrative, or aesthetic manipulation, he just gently keeps redirecting our attention to the biggest, most distressing, and in the end most liberating of themes. You are not (just) your name, your resume, or even those conflicted ideas battling for supremacy of an egoic identity. Instead, we’re each of us a loaded, double-barreled question. And at the same time, the targeted answer. I am, not because I think it so; but simply because I Am.

Our individual life spans are so relatively insignificant, and yet so rich with desire, poignancy, affection and hope. As I meandered through this exhibition, its installation as spare as the mind after a week on a mountain, a poem by the late Korean Zen master Seung Sahn echoed through my head. Kawara’s dedicated, lifelong effort embodies and generates the same kinds of questions, forcefully demonstrating ways for art to continue to transcend the market, fashion, academic specialization and tenacious yet outmoded notions of taste.

Coming empty-handed, going empty-handed – that is human.

When you are born, where do you come from?

When you die, where do you go?

Life is like a floating cloud which appears.

Death is like a floating cloud which disappears.

The floating cloud itself originally does not exist.

Life and death, coming and going, are also like that.

But there is one thing which always remains clear.

It is pure and clear, not depending on life and death.

Then what is this one pure and clear thing?

On Kawara: 10 Tableaux and 16,952 Pages

Dallas Museum of Art

May 18 – August 24

Titus O’Brien is an artist and writer who lives in Dallas.