Where Clouds Disperse: Ink Paintings by Suh Se-ok creates a contemplative space in the rear galleries of the Museum of Fine Arts , Houston’s Caroline Weiss Law building. Curated by Christine Starkman, curator for Asian art, and Barry Walker, curator of prints and drawings as well as modern and contemporary art, Where Clouds Disperse appears as part of the museum’s Asian art initiative. The MFAH has made a commitment to bring new emphasis and focus on the art of a region that, having already exerted a profound influence on this country’s history, will assume an increasingly important role on the world’s stage as this century unfolds.

The initiative began with the opening of the Arts of Korea Gallery in December, adjacent to the galleries holding the Suh exhibit, and will continue with the renovation and reinstallation of the Asian galleries upstairs. The new gallery augurs well for those renovations; it is spare and beautifully lit with an eye toward subtle detail. Note the unobtrusive display cases; their glass fronts are held in place by discrete channels set into the floor.

The majority of the objects currently on display are on extended loan from the National Museum of Korea, the oldest being a comb-patterned earthenware vessel dated from 4000 B.C.E. Other pieces of interest are some contemplative Buddhas, lovely examples of Korean celadon and other porcelains and an impressive, if actually quite small, bronze Buddhist bell (often they’re taller and wider than a man). At the opposite end of the gallery are works by contemporary Korean and Korean-American artists, such as a large monochromatic painting by Byron Kim, Flight of the Kingfishers, reminiscent of early Brice Marden and so recent it still has that new-painting smell.

The plan is to exhibit the ancient, the merely venerable and the contemporary all together, keeping a dialogue going between the past and the present. If that’s the model for the rest of the Asian galleries, it bodes well.

Which takes us back to Where Clouds Disperse. Suh Se-ok was born into an aristocratic family in 1929, where he was trained from childhood in calligraphy and classical poetry. His abstract ink paintings first drew attention in the 1950s; as an artist and teacher, he founded the progressive Mungnimhoe, or Ink Forest Group, in the 1960s. Suh taught for decades at the Seoul National University, his alma mater (described by one of the curators as the Harvard of Korea), where he is now professor emeritus. He continues his artistic activities – painting, writing poetry, carving the seals with which he’s stamped some of his paintings – and he can be observed doing so in the two videos that accompany the exhibit.

The Mungnimhoe group was interested in exploring the abstract possibilities of traditional ink painting, experimenting with different effects of brush and ink on various kinds of paper, and thereby conflating the modernist abstract impulse with the concerns of traditional ink painting and calligraphy. They were also interested in the contrast between form and void, and nowhere is that more evident than in the exhibit’s eponymous painting, Where Clouds Disperse (1977). The ink markings, all vaguely circular, cling to the edges of the paper, even sliding off, leaving the center a blank empty space. Or is it? In Daoist thought (to greatly oversimplify), emptiness is full of potentiality; being is always preceded by non-being. It doesn’t take long for that empty space to begin to have presence (even nothing is still something). And, where clouds disperse, there is clarity.

Suh Se-ok’s art is an art of process, of getting back to the basics of making marks that carry meaning out into the world, as two of the earliest paintings in the exhibit, both from 1959, Line Variation and Point Variation, make clear. These are straightforward, self-descriptive works. Both on mulberry paper, they explore the relationship between brush, ink and paper, as well as the basics of mark making. The point is the fundamental mark, and we know from basic geometry that a line is a series of contiguous points. In these two paintings, a point shows up among the lines, and several points get together to form a few short lines amidst the points. These two gestures are the building blocks of Suh’s art, and he makes virtuosic use of them.

Mulberry and rice papers are unforgiving media; once a mark is made, it can’t be unmade. There is no going back or doing over. A video shows Suh creating one of the paintings in the exhibition. One is reminded of the action painters of the New York School in the 1940s and 1950s, painters like Kline and de Kooning, who (unlike Pollock) made studies before committing brush to canvas. Suh works the same way, thinking through compositions before taking the biggest ink brush I’ve ever seen and laying down his composition in sure, vigorous strokes. Watching him paint (and hearing him occasionally grunt like a tennis pro as he does), you gain a greater appreciation for the sheer physicality of these works and the effort they require, especially the larger ones. There is planning and premeditation, but Suh’s art still happens wholly in the moment.

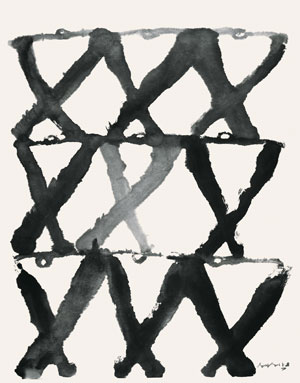

Though abstract compositions, most of the works in Where Clouds Disperse are titled either Person or, more commonly, People. Some of them possess a certain anthropomorphic aspect, perhaps people seen from above; perhaps people dancing. Some works are as monumental as ink on paper can be, but still retain a kind of lightness. Some are so wispy as to be insubstantial. But most of these paintings are so resolutely abstract that the titles strike me more as affirmation than description.

Humans – people – are the only creatures that make marks that convey meaning (other creatures leave marks, and those marks are unambiguous to their kind), and Suh’s art is a meditation on the act of making marks that convey meaning. Paintings like the 1992 Person, the 1996 Person and the 1998 Person evoke the wielder of the brush as much as, or even more than, they suggest human figures. There is something of post-war existentialism to this – the painter as man of action. But there is something of the process art of the early 1970s as well, with the emphasis on the basics of mark making in the context of time. But this may simply suggest that the three figures who have most profoundly shaped Korean, and, for that matter, east Asian sensibilities – the Buddha, Confucius, and Lao-tzu – all got there first.

There are quibbles with Where Clouds Disperse. One could, perhaps, wish the lighting of the exhibit be a bit more subdued, more Rothko Chapel than Target, but that’s probably a limitation of the physical plant (the gallery lacks any directional lighting). But the ink paintings of Suh Se-ok create their own ambience. The great strength of these paintings is that they quietly, and with integrity and dignity, draw you into contemplation, regardless of their setting.

John Devine is a writer living in Houston.

All images collection of the artist.