One’s first impression of Mary Heilmann: To Be Someone, organized by the Orange County Museum of Art and curated by Elizabeth Armstrong, is that there are too many paintings. The exhibit seems drastically overhung, and with each painting distracting you from its neighbors, it’s difficult to focus on any one work. The paintings march along the walls and around the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston with their brilliant, garish and sometimes clashing colors screaming for you to look at them. There’s no direction, no indication as to where you should—or could—begin. There’s just too damn much to pay attention to.

But you’ll get used to it. Even start to enjoy it. Like a busy city street, say, in Manhattan, if you remain open to it this exhibit will eventually draw you past the sensory overload and begin to beguile you, charm you, seduce you. There’s a vitality in this work; a playful yet earnest energy, even a theatricality that, especially when encountered en masse, is hard to resist.

Mary Heilmann was born in San Francisco in 1940, just in time to be a Catholic schoolgirl shopping in ecclesiastical clothing stores for black stockings to fit in with the Bay Area Beat scene of the 1950s. She studied literature at the University of California, Santa Barbara, but perhaps spent as much time hanging out with surfers and artists as she did at the library. Receiving her BA in 1962, she took classes in poetry and ceramics at San Francisco State University before moving on in 1967 to take an MA in sculpture at Berkeley. Heilmann moved to New York that same year, excited by what was happening in minimalist and conceptual art circles at the time. But, being a Californian and a woman, she was an outsider twice over in the artists’ boys’ club that hung out at Max’s Kansas City. So Heilmann, the perennial rebel, took up the then much maligned practice of painting. Her challenge, as curator Armstrong puts it in her catalog essay, was “to find a way to paint while rejecting the history of painting.”

Based on the evidence of the present exhibition: mission accomplished. Heilmann is less a painter than an artist using paint to make objects. She’s not much concerned with illusionistic space, or brushwork, or figure/ground relationships (though the last of these will occasionally occur all the same). Following the Minimalists, Heilmann very much wants the viewer to pay attention to the surface of the painting; the way the paint has been applied, inviting one to try to tease out the order of the painting. The object is what it is and that’s all that it is. But, unlike the Minimalists, she doesn’t hide the artist’s hand behind a fantasy of immaculate fabrication; quite the contrary, the evidence of the artist’s touch is the point. Take one of the earliest works in the show, Little 9 x 9 (1973), a small red painting with nine horizontal and nine vertical lines forming an irregular, partially woven grid. But the pattern of lines hasn’t been painted, the lines have been gouged out of the red paint by the artist’s finger, revealing the dark underpainting and creating a sculptural effect. All this points to the process, as revealed by the trace of the artist’s hand, as the real “story” of the painting.

There are other stories in these works, most of them likely to bring a smile. Chinatown (1976), part of a series of paintings that plays within the limitations of the three primary colors, is a big red diptych, one painting a deeper red than the other and each with a slightly contrasting, broad red “frame” painted around its perimeter. When you approach for a closer look (and those contrasting reds will draw you in), you discover that the edges of one are a pale yellow, the edges of the other a pale blue—cool colors peeking out from under their red-hot blankets.

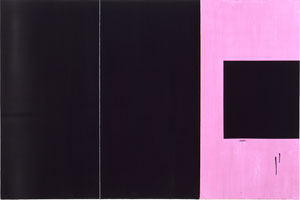

Heilmannn presses the object-ness of her work. She creates flat ceramic sculptures that she hangs on the wall like paintings. Kachina (1985), is the thickness of a painting and consists of a smaller square set atop a larger square, both in the same black and white checkerboard pattern. Heilmannn also often works with shaped canvases, creating mutated paintings like Chemical Billy (2001), in which a painting seems to be sprouting multiple canvases. Most of the piece is covered with a sickly limey green, in brushstrokes so loose and haphazard that to call them loose and haphazard is to credit them too much. Bands and dots of bright color join the fray. Despite the vivid brushwork on the canvases’ surfaces, the work’s multiple parts resist being read as a “painting,” seeming to insist on being an object.

But perhaps that states the case a bit strongly. Heilmann doesn’t really insist on much of anything, which is not to be confused with a lack of backbone. She is the most laid-back of artists (how many other artists would provide club chairs, fashioned of brightly painted plywood and polyurethane webbing, for the comfort of the exhibition visitor?). You can make of her work what you will; she won’t mind—that’s part of her strength as an artist and, one suspects, as a person. She’s lived her life and made her art as she’s wanted to. It’s no accident that the show’s eponymous painting, To Be Someone (2004), is perhaps the most unprepossessing work in the show; it almost gets lost amidst all the hustle and bustle. I won’t describe it, but go find it. It’s a charming, provocative little object— not so much an unnecessary self-assertion by Heilman as an invitation to her viewer.

John Devine is a writer living in Houston