So much has been written about the US-Mexican border, and so many stereotypes and assumptions, artistic and otherwise, have been made by people who have never been here, that the El Paso Museum of Art (EPMA) thought it was time to explore the art that is being created by artists who live along this 3,000-mile boundary.

Christian Gerstheimer, curator of Sister Cities: Testing Boundaries, spent nine months selecting the work of artists who live on either side of the border that runs from San Diego to Brownsville.

He established two criteria for the show: One was that all of the artists had to be currently living on the border, and the other was that the work had to test boundaries ― physical, aesthetic or conceptual. Gerstheimer emphasized that the show was not intended to be about the physical border so much as about boundaries in general.

Choosing artists from this wide a geographical area is something of an impossible task ― there are so many artists working in so many different media that it must have been hugely difficult to narrow things down. But he has chosen a fair cross-section of different media and different conceptualizations.

Of course, as Albert Fierro, chief of cultural affairs for the Mexican Ministry of Foreign Affairs and former general director of CONUCULTA, pointed out in a panel discussion, there is really not just one border, but many different borders ― that is, how people live and interact along this boundary varies widely. This is certainly true of how artists relate to this particular environment. At that same discussion, Carmen Cuenta from INSITES in San Diego-Tijuana showed slides and talked about all of the various joint art projects in San Diego-Tijuana. To a great extent, these have developed in direct response to the wall that has been erected and extended out into the ocean, dividing the two countries. She showed sides of the human cannonball that was shot from a cannon on one side of the border over to the other side. She showed a project to cut a hole in the wall featuring tubes, which enabled people on both sides to drink water from the same pipe.

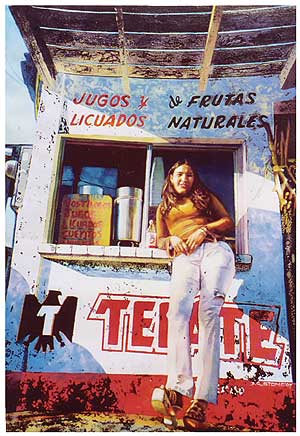

All of these projects were created with the help of everyone who was in any way connected to the scene ― border patrol and citizens, as well as various city and neighborhood groups. These groups were able to erect sculptures that they ensured would not be vandalized by consulting people living in the community to explain what they were going to build, which made everyone “co-participants.” As a result, pieces that at one time would have been soon destroyed are now protected. Furthermore, people in the community have set up food stands and T-shirt stalls to sell their wares to tourists who came to see the art projects, making the artwork a real part of their community.

Margarita Cabrera...Vocho...2004...Vinyl, thread, car parts & mixed media...6 x 13 x 5 feet...Courtesy of The William J. Hokin Collection

INSITE members seem to be focused on the border as the principal subject, attempting to create projects that play with the border and trying to emphasize unity where there is a very prominent barrier to it. In El Paso-Juarez, by contrast, a more formal cooperation was established, with joint shows at museums on both sides of the border: While there are very informal discussions between a few artists who have friends on each side, for the most part everyone operates independently.

On the other hand, there is such a free flow of people back and forth between El Paso and Juarez that for many the border is more a hindrance than anything else. As a result, work from artists in Juarez tends to focus on other concerns altogether. One of the interesting aspects of the current EPMA show is that the majority of art that concentrates specifically on border issues seems to be the work of people living on the US side. Cecilia Briones, La Catrina, of Juarez told me, “We really aren’t limited to these stereotypes of what border art is supposed to be like.” She said that “everyone has a belief that the border means violence, use of certain colors and images, but there is so much more going on here.” Her abstracts and use of found images reflect her her artistic and social concerns, but those concerns have little to do with the border as such. Andrea Gussi, also from Juarez, is represented by her sculpture Skin series #3 portraying a female form made from wire, goatskin and light. It is part of a much larger series simultaneously on display at INBA Museum in Juarez featuring similar forms. She is a Mexican artist whose artistic concerns are unrelated to the border. Her painting and sculptures often have an otherworldly, spiritual quality to them.

Nevertheless, the show contains many pieces that play exclusively with stereotypes and the border, often in funny as well as highly charged political ways. The brothers Einar and Jamex de la Torre, who live on both sides of the border in California, make Toltec figures using pop culture items ― a television set featuring norteno singers for the face, rifles for arms, the whole piece (comprised of these kitschy items) forming an ancient deity figure. Alfred Quiroz from Tucson has painted a huge canvas called Border is Shoes, a painting filled with images of Canadian Mounties carrying a book of NAFTA rules, border patrol guards wildly shooting guns and logos of pop products.

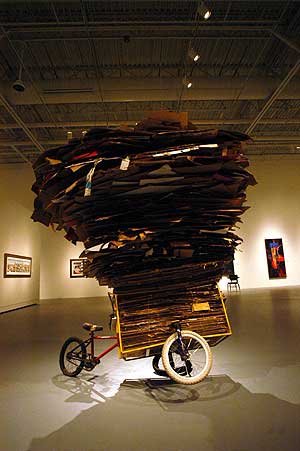

Gilbert Rocha from Laredo has piled on a bicycle cardboard reaching to a nearly impossible height, reflecting a reality often seen there. Gaspar Enriquez from El Paso also paints a familiar reality: He grew up in El Paso’s poor and politically charged second ward, and he paints those people with whom he grew up. These are deeply respectful portraits of individuals who are often marginalized by the rest of society. Indeed, he explained that one portrait in the show is not, as some critic complained, glorifying a drug dealer, but is actually a portrait of an incredibly talented tattoo artist who was a former student of his. The man sports various slogans and gang-like marks on his body, and Gaspar wanted to pay homage to his talent.

Mauricio Saenz...Abyss has no end; pero no le digas a...nadie que yo te dije...2006...Mixed media on masonite...39 x 59 inches

Likewise, Margarita Cabrera, who was born in Monterrey and who spent a great deal of her childhood in Mexico City, but who now lives in El Paso, pays homage to maquiladora workers by replacing the plastic parts of common household items made in the maquiladoras with vinyl replicas. She wants to make us aware of who makes those items we use daily. She also pays homage to the Volkswagen Beetle, which for the urban Mexico City dweller might well be compared to the camel for the Bedouin: It is used for everything. She made a full-size soft sculpture of the Beetle by taking a Volkswagen apart and replacing all the metal parts with vinyl counterparts. Just as the Beetle is used for everything in Mexico, nothing here went to waste: Margarita revealed that she actually put the original Volkswagen she had taken apart back together with various used parts, and it is now for sale.

The Aiko collectivo from Juarez, whose name comes from the Japanese word for “dream child,” normally works with ideas of childhood fantasies and fairy tales. Here they have made a piece specifically for the show with elongated figures pulling on a line that almost looks like a clothesline, but is, of course, the border.

The popularity of the collectivo, here represented by several different groups, points to a fairly interesting difference between the two countries. While the US does not have a Ministry of Culture, Mexico, like almost every other country, does. Museums cannot arrange shows on their own the way they can here, but have to involve the government in Mexico City. With governmental control over the arts, there is not really, at least in Juarez, a well-developed system of galleries: People either show their work in restaurants or go through the government for exhibitions. As Jose Badia and Oriana Richaud of Aiko pointed out, they are more likely to get governmental support if they can show there are many people involved, therefore the rise of the collectivo. “Plus,” Jose said, “I am really social, so I like to have people around me when I work.” They also like the anonymity, which comes from belonging to a collectivo rather than promoting themselves as individual artists. Many artists, however, do both. Andrea Gussi, for instance, exhibits individually, but in the fall she will be part of a collectivo doing an art project in Oaxaca.

The EPMA show is fascinating in its scope and range of interests. There are eerie nighttime landscapes of illegal border crossings, as seen through a border guard’s field binoculars, by Louis Hook of San Diego; a Luche Libre construction designed to make a political point; and representations of taco stands and pop culture by Gregg Stone from California. The border is a unique culture, producing its own world. As Fierro pointed out, “It is a crossroads between two different ways of doing things … where the Anglo-Saxon world meets the Mexican world; it is a place where people are often preparing to move and where waiting ― waiting for visas, waiting to cross ― is a fundamental part of the life and where there is an endless case of exchanges and opportunities.”

Reams of information could be written about the subject. To look at all of the artwork ― political, funny, angry, lyrical ― is to get a sense of the wide variety of artistic life on the border. The exhibition perhaps most importantly has helped to begin a dialogue among those of us who live here, and to keep far away the often strident rhetoric and misperceptions about our region that blare at us from the airwaves daily.

Images courtesy El Paso Museum of Art

David Sokolec is a writer living in El Paso.