We don’t often think of art as something that’s transplanted, yet its

occasional roaming nature makes it just that. Assessing the work on the

wall for what it is, for what it isn’t and for what it might be, we

forget that when we leave, the work at many venues will be packed and

shipped for others to see elsewhere.

Anyone traveling to the art fairs

this summer will tell you how important the space is to contemplating

or enjoying the work.

With these thoughts in mind, curator Florencia Braga Menéndez has created a colorful, collective portrait of improvised and informed contemporary work in Expansive Link, an exhibition of 17 contemporary Argentine artists at DiverseWorks.

The structure of the exhibition was inspired by a popular Argentine children’s game called “The Invisible Friend,” wherein kids are given a gift by a mystery peer and asked to identify the gift giver through a string of questions. By giving a gift to each of the artists featured in the exhibition, Menéndez essentially laid down invisible guidelines for the development of the new work in the show, the majority of which are installations or site-specific. She first visited Houston in January of this year and was seduced by the city’s vast artistic melting pot. A select group of up-and-coming South American artists was later transplanted to Houston the week before the opening and encouraged to create in response to their surroundings. The gift the artists received was, in fact, the entire city. The result is as colorful and rich as Houston’s own cultural landscape, and exceedingly playful.

The word “colorful” suggests a certain tenor or intensity, even a certain cheerfulness. The power of that word seems to resonate, not only in the palette used in many of the works, but also in the manner in which much of the work was composed. The theme of child’s play pervades much of the general aesthetic of Expansive Link, either literal play or simply flirting with the concept. Ariadna Pastorini’s Pretzel is a video of two gloved hands twisting and turning a large version of the titled snack above various moving landscapes, sometimes even attempting to use it as a steering wheel or to mimic an airplane. When the pretzel is held upright, it reveals what might be a smiling “face,” not only conveying the concept of playing with food literally, but also personifying it so as to communicate the kind of playfulness associated with it.

There is a some form of fun and frivolity in nearly every piece in DiverseWorks’ main gallery, which has been transformed into a site-specific art playground. Alexa Horochowski’s El Zorzal Criollo is a low-rider-like steel “bed” equipped with hydraulic switches, airbrushed pinstripes and Old English stenciled letters. Stripped of its car status, this macho Chicano cultural symbol becomes instead a glossy and androgynous minimal sculpture. Its title is the nickname of legendary Argentine tango singer Carlos Gardel, who in the 1930s garnered international fame and popularity along both shores of the Río de la Plata, an estuary that separates Uruguay and Argentina. El Zorzal Criollo is a not only a monument in this sense, but also a home for the pairing of Chicano and Argentine cultures, low and high art.

The youthful music of Max Cachimba’s cartoon animated video installation, reinforcing the sense of the gallery as a site of oddly collected merriment, is hardened by his adjacent oil paintings, which are truly remarkable in detail and palette. Macabre personifications of an egg, a house and a duck are carefully scattered on small canvases in dark, rich colors, informed by children’s stories as if from a nightmare of Humpty Dumpty’s. Eyeless caverns hang on hollow faces with just enough humor to balance the darker half of the installation, bringing a much needed “mature” perspective that is still in keeping with the exhibition’s amusements.

The most painterly works, however, belong to Victoria Delrieux (Musotto)’s site-specific and embellished abstracts. Not unlike the work of Giles Lyon, seemingly random and muddled forms have been carefully outlined and sometimes shadowed, in this case in ink, as if to diagram and “cartoonize” each brash and unpredictable placement of paint. Spontaneity is thus marked by irony and control, and gesture is almost self-mocking. On the gallery floor and across the room on the gallery wall, Musotto’s self-titled work is versed in abstract expressionism, but the artist has attempted to free it of its non-representational origins by implementing the values of graffiti art, breathing scattered toothy faces into the many layers of brightly colored paint.

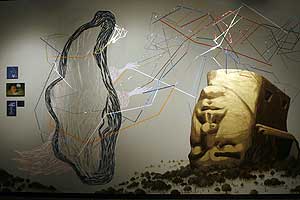

Marina Sabato’s Tintas seems out of step with the exhibition, and it’s no surprise they have been relegated to a small corner. They are the only featured works on paper and two of the three pieces are completely devoid of color. The ink drawings bear the images of indigenous people clothed in headdresses resembling wolves and dogs, and while the patterns of their garments are richly complicated and the gestures of the subjects suggest a subtle playfulness, the appeal to frivolity is almost entirely absent. They are also the most outwardly ethnic of all the work in the exhibition, in contrast to neighbors that include an amalgamation of brightly colored melted plastic toys by Rafael Gonzáles Moreno and a giant surreal mural by María Guerrieri and Max Gómez Canle. For a show that speaks so highly of color and jollity, these works, while beautiful in their own right, seem to disappear into the background.

It’s no secret that much of Latin American work in the twentieth century has been marked by the influence of realism, surrealism and, most recently, pop art, leading to such movements as muralismo and the success of artists who advocate post-Eurocentric and indigenous values. It’s refreshing to see the deconstruction of those values here, the fragments of which have been used to build a vivid atmosphere of inspired work that speaks to its own originality. The collectivist approach to the space makes for a loud and assorted mescla of fresh contemporary perspectives, sweetened only by the rich qualities of their home country that have been transplanted from Buenos Aires to Houston.

Images courtesy DiverseWorks

Evan J. Garza is a writer currently living in Houston.

1 comment

those Argentinian high art Modernists have been rubbing elbows with Brazilians, maybe?

A generation after the South American op art- minimal sculpture- geometric abstraction; these seem to be similarly insulated and internal systems- but with a good amount of traditional rediscovery through collectivism and international reevaluation of locale.

I wonder what those artists did when they were in town?