Rebecca Holland’s new work at Barry Whistler Gallery is precious and ironic at once. The pastel

colors — pink, yellow and chartreuse — of the translucent planks,

square sheets, brick-o-blocks and beat-lines on the wall signify in

pretty, feminine fashion. They tickle the eye.

At the same time, Holland casts her material of choice, sugar, into minimalist shapes that read like prefabricated industrial forms. The pastels thus are a dainty thumb in the eye to the grisaille machismo of Donald Judd, Tony Smith and Carl Andre, three forebears to whom Holland no doubt pays homage.

Holland may give a wink-wink, nudge-nudge to the men that came before, but her goals are entirely her own. In talking about her work, she says, “Yes, the colors are mocking. I am looking for something ridiculous.” There is, though, a very serious formalist compulsion at the root of her practice that comes to fruition in the striking end product. In using melted sugar mixed with food coloring, “I am trying to make colors that are simultaneously electric and transparent,” Holland explains.

Holland has developed a unique process. She uses “super sugar,” a very strong grain of beet sugar used to make cake decorations. She heats it up slowly and carefully in order to avoid caramelization, mixes it with water, adds food coloring and pours it into flat, orthogonal casts that are open at the bottom and sit on broad sheets of paper. Until she seals the objects in polyurethane, they are sticky and vulnerable to rapid decay; when added, the plastic coating of polyurethane creates an extra dimension to the sugar objects. In Green Planks, 12 78-inch boards lean up against the wall. When one looks at the calcified sugar head-on, the objects are luminous and prismatic. From a sideways perusal, one can distinguish between the sugar and the polyurethane, seeing the green plank of sugar set inside the resin varnish. Viewing the few centimeters between the plastic edge and green body makes for great pleasure and subtly.

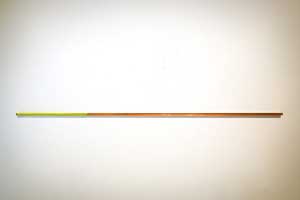

We might see this difference between the frontal and the oblique as a second dialectic at work in Holland’s sculpture (the first being the play between the aforementioned preciosity and irony), instructing us in how to look at her work. In Hot Candy Lines, Holland shows her penchant and talent for installation. Two lines of sugar have been coated in polyurethane and cast in a thin aluminum bar that lines the wall at about eye-level in two galleries. These two lines of sugar in two different rooms, when seen from afar, create a continuous line. The walls between the rooms break the space, but the line continues, at least when the viewer stands back and looks directly at the face of the walls, unbroken.

From the side, one sees the incredible craft at work in Hot Candy Lines with the tongue-and-groove fitting between the sugar and the aluminum bar. In creating such a snug fit between sugar and aluminum, Holland makes it seem as though she has slid a dowel rod of sugar into an open groove. The relationship between the materials is tectonic in nature: the tightness plays up the jointure, and thus the architectural quality, of her work. Holland admits as much: she claims forthrightly that her work is architectural in nature. As painting-cum-installation, the work she creates is site-specific and often interacts with the surrounding architecture or, like the work of Jim Lambie, sets in relief the architectural detailing. In Glaze (2003) at the Mattress Factory in Pittsburgh, Holland installed sheets of translucent green, unvarnished sugar on the ground floor of the museum. The green floor heightened the creepiness of the water-stained walls and overall dank space. As time passed, the sugar melted and seeped down into a drain in the corner of the cavernous room. Recently on view at the Lehman Gallery at the City University of New York, Holland’s Long Crush is another installation piece. Reminiscent of the candy pieces by Félix Gonzalez-Torres, a shallow heap of yellow-green cast candy has been installed on the floor in the gallery.

Rbecca Holland...Hot Candy Lines...2007...Cast sugar, polyurethane, aluminum...1/2 x 3/4 at varying lengths

Other contemporary artists that spring to mind when looking at Holland’s work are Tom Friedman and Janine Antoni. Similar to their work, there is an ephemeral quality to Holland’s art. The difference is that Holland’s work looks transient but isn’t. The polyurethane makes the pieces more durable and, hence, more collectible: they are works of sculpture to be owned. I would argue, however, that the plastic sheathing adds to the work aesthetically, heightening the tension between heroic minimalism and cutesy plastic object. Like steel, plastic is a manmade, manufactured material. Unlike steel, it is often soft and malleable. The plastic, like the sugar itself, is an ambiguous material.

Then again, Holland’s pieces are resolutely ambiguous to the core. She uses ephemeral material to make permanent objects. In Sugar Blocks, for example, Holland has used yellow-dyed sugar to cast pellucid and light-refracting blocks in the shape of cement brick-o-blocks.

It is work that is quiet in its simple shape and yet raucous with intellectual suggestion.

Images courtesy Barry Whistler Gallery

Charissa N. Terranova is an Associate Professor at SMU and a Contributing Editor to Glasstire.

1 comment

edible minimalism