GUANTÁNAMO: Pictures from Home, Questions of Justice, conceived by

Brooklyn-based photographer and installation artist Margot Herster, was

inspired by her husband’s experience as a lawyer for suspected

terrorists detained at the U.S. Naval Base in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba.

In the aftermath of 9/11, White House counsel Alberto Gonzales and President George W. Bush resolved that non-U.S. citizens imprisoned abroad, say, in Cuba, have no protection under Article 4 of the Third Geneva Convention, which left detainees little recourse in U.S. courts. It was not until 2004, when the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Rasul v. Bush allowed prisoners to challenge their detention through habeas corpus, that lawyers like Herster’s husband began visiting Guantánamo. These visits were halted in 2006 when Bush suspended the federal courts from hearing such petitions by establishing the Military Commissions Act, an act that was upheld a year later by a Circuit Court of Appeals in Boumediene v. Bush, indefinitely forestalling further challenges from detainees and their attorneys. GUANTÁNAMO provides a well-rounded view of the obstacles faced by these men and their attorneys, from journeys through the Middle East to meet their clients’ families; to stays in Cuba, where they patiently traversed the bureaucracy of Guantánamo and attempted to extract information from clients who were rightfully reluctant to chat with potential interrogators; to personal and professional criticism at home for defending “unlawful enemy combatants.”

The exhibition opened with Inside Guantánamo, a sound installation by Herster and Houston-born, Miami-based photographer Carolyn Mara Borlenghi. Sitting in a darkened room surrounded by speakers, viewers listened to lawyers for Guantánamo detainees describing interactions with their clients. Each excerpt was followed by declassified trial testimony from the detainees themselves. The rest of the exhibition continued in that vein, from audio- and text-based accounts by the attorneys to mostly visual representations of their clients and their families.

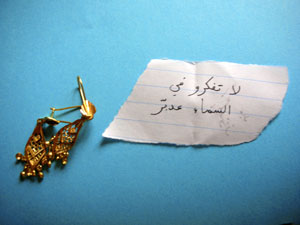

Herster divided the bulk of the show into five sections by country: Yemen, Afghanistan, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Bahrain. Each segment began with comments from a lawyer describing how he or she came upon the case, followed by one photograph after another (each one labeled with the client’s name, native country and legal representation) and further excerpts from interviews with the lawyers. Attorneys Sarah Havens and Doug Cox, for example, explained how their client Abdulaziz Al Swidi asked them to deliver gifts to his family, while Kristine Huskey, the lawyer for Fuad al Rubaish, talked about how Fuad’s family asked her not to tell him that his father had passed away. The former was accompanied by a picture of a gift, while the latter was paired with a photograph of Fuad’s deceased father. (Given the social status of women in the Arab world, the only women represented in any of the photographs were the American lawyers, outfitted in dark clothes and head coverings.)

Although this format might seem to lack variety, each group was actually so concise and the cases so distinct that I, for one, read through every inch of the accompanying didactic material. The consistency made the information that much simpler to internalize, although I was still troubled by encountering so many similar accounts of unlawful imprisonment. The same could be said for repetition throughout the exhibition — within the layout as well as through an echoing of the information itself. Almost immediately, I realized that the text on the wall was also being spoken aloud in the video of recorded interviews with the attorneys. Broken into four parts — “It seemed like the right thing to do,” “It’s a Caribbean island with no tourists,” “The person in the orange jumpsuit” and “The families now see us as the people that are taking care of their children” — this audio-visual component added even more weight to the words on the wall, often revealing emotions like disbelief, frustration or sadness that were absent from the text. This layering of audio, text and visual imagery within the exhibition gave depth to Herster’s presentation, even as it helped clarify her complex subject.

The photographs in the exhibition had a dual function, acting as both conceptual devices and documentation. Initially, attorneys photographed identification cards and family pictures to document their research about a given client, creating photographs of photographs. The lawyers eventually began using photographs to gain a client’s trust, documenting more of the detainee’s native country, for example, or taking self-portraits with the individual’s family. A few DVDs scattered throughout the exhibition even showed some of the families introducing the lawyers, and then asking the detainees to trust them. Together with the testimony, these different types of photographs became surrogates for the prisoners — symbols for how they are seen or, more accurately, not seen by the outside world. Yet, despite the overwhelming number of interviews and their corroborating images, I felt only slightly closer to the inmates. None of the images showed a client in captivity (a few showed freed men returned to their native country), and rarely did the accounts come from the detainees themselves — they were either recounted by lawyers or interpreted by translators. As such, it was evident throughout the exhibition that Herster and the lawyers had filtered the information about the detainees, not unlike a letter censored by security before reaching its intended recipient or information about a hunger strike passing from Guantánamo to a U.S. newspaper. Although this distance could have been an unintentional result of the measures that prevented lawyers from gaining information about their clients, its resonance in the exhibition itself actually served as a potent metaphor for those barriers.

Exhibitions like this one, steeped in political iconography, frequently leave viewers contemplating the subject more than the artwork. Although Herster certainly left viewers thinking a great deal about the Guantánamo Bay detention facility and its inhabitants, I was equally impressed by the artist’s ability to effectively render the debate within the limits of an art installation. I know I left the show thinking as much about her accomplishment as about the issue itself.

Images courtesy Fotofest and the Collection of Through the Walls by Margot Hester

Margo Handwerker is a Curatorial Assistant of Prints & Drawings and Modern & Contemporary Art at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston.