There is a clever gender technique at work in the art of Margaret Meehan and Lesley Dill: a manner of bearing sexual specifics through form while avoiding one-liners, propaganda and essentialism.

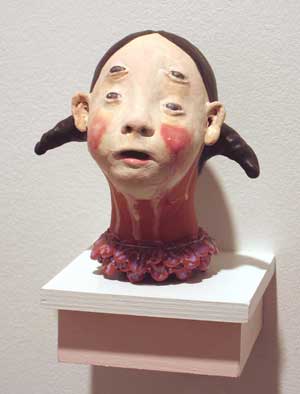

There is a clever gender technique at work in the art of Margaret Meehan and Lesley Dill: a manner of bearing sexual specifics through form while avoiding one-liners, propaganda and essentialism. With work that is in equal parts and different ways 'feminine,' theirs is a politics of subtlety communicated by way of ambiguous form. Meehan makes small pink-and-pretty ceramic girly heads with fanged mouths and a few too many eyes. Dill’s tendrils are hairy in the right way: blanched horsehair dangles from lines of Kafka rendered in gnarled thin wire above.

Not so long ago, the descriptor 'feminine' was an only thinly veiled mode of denigration. To call Eva Hesse’s quirky strain of Minimalism feminine and, worse yet, organic was no simple means of pragmatic description. It meant her work was subjective and emotional in comparison to Judd’s cold, serial, author-killing steel boxes. In Accession I (1967), Hesse made the galvanized steel box of Minimalism fingery and oceanic by weaving rubber tubing through its perforated walls. She transformed the radically regularized objects of Minimalism into irregular things: she made them woman. Hesse feminized an art form that was largely the bailiwick of men. And she did so by deploying the critical act of appropriation, what for the French philosopher Henri Lefebvre is tantamount to the 'turning of the world upon its head.' Hesse was an appropriator before it was à la mode – before Judy Chicago’s Red Flag (1971) made it okay to pull your tampon out in public and before Sherrie Levine’s critical-minded hijacking of the photographs of Walker Evans and watercolors of Matisse in the 1980s.

We find ourselves in the midst of a quiet yet calculated rethinking of one man’s deadliest nightmare – the renewal of Freud’s vagina dentata as happy-go-lucky giggly maw. Let cunt art reign! In 1972, the gals from Fresno State — Judy Chicago, Faith Wilding, Miriam Schapiro, et. al. — established cunt art in the form of Womanhouse, a 17-room Victorian abode transformed into the temporary site of feminist exploration and experimental art installation. They took back the cunt in order to throw it in the face of the world.

In the same 1970s spirit of cunt art, Meehan and Dill appropriate the feminine. They make palpable the sometime surrealism of 'what it feels like for a girl,' to quote Madonna, that maven of womanhood and Mae West femininity.

Installed in the small windowless space of Gallery 219 at Eastfield College, Margaret Meehan: Innocence and Otherness combines drawing, decorative wall painting, and sculpture. The walls are painted in pink stripes and undulating smooth-edged waves. Meehan creates an environment of 'memory and metaphor,' to use her own words. The pretty-in-pink walls suggest fond childhood memories that remain fond only for an instant. Very quickly the room becomes a space of meditation on the bizarre in pastel — the dream world located under the scalloped lace of a light-cherry-colored canopy bed. Metaphor intervenes as the color pink suggests at once girl princess and her opposite. Cutely deformed heads mounted on small shelves adjacent to gouache and pencil drawings line the wall. Meehan renders the head Geraldine with a growth. Eloise has dark rings under her eyes. The ceramic head of Ann(e) has no mouth. The small pate of Imogene has an eye in one socket and sharp-toothed chops in the other. The feminine action of this work brings to mind the video projects of the Swiss-German artist Pipilotti Rist. Like the blithe violence of Rist’s Ever is All Over (1997), a video showing a smiling woman in a blue dress and red Dorothy-of-Oz heels bashing car windows with a flower-topped mallet, Meehan pulls the rug out from under the poetic refrain of girls are sugar and spice and everything nice while boys are snakes and snails and puppy-dog tails. If Rist’s alter ego is Pippi Longstockings, then Meehan’s is Ramona Quimby on LSD fused with Penny from Peewee’s Playhouse.

Lesley Dill takes a tack that is less violent than Rist but informed by an oddbody formalism that resonates with Meehan’s work. Installed in the large gallery space at the McKinney Avenue Contemporary, the work of Dill is craft-like, diaphanous, and best of all, faintly strange. It is the suggestion of weaving brought about by her use of fine filaments coupled with tactile reference and the body that makes Dill’s work 'feminine.' Her sculpture can be precious and ruminative, as with the cascades of horsehair in the wall-scaled Blonde Push, and it can be almost derivative as with the shredded red organza suit, To Be Alive Is Power, that brings to mind Claes Oldenburg’s Giant Blue Pants (1962). Unlike Oldenburg’s pop-infused pants, Dill’s work is ethereal and ghostly. The would-be spiritualism of her work makes its most potent aspect — the oddity of the hair and twisted-wire words combined — seem only accidental, and not in a good way. The surrealist stream-of-consciousness language of Copper Poem Dress ('positive as sound…It beckons and it baffles philosophy') injects the otherwise straight-faced seriousness of the piece with a feeling of uncertainty.

Of the two shows, Meehan’s is ultimately the stronger. In her appropriation of language and cultural affect, and here I refer to the attribute 'feminine,' Meehan succeeds in transforming this age-old quality into something newly unsettling. Meehan stretches the feminine into the realm of the feminist by transforming the proverbial cuddly lass into alienated girl-form. Meehan’s pieces are ceramic non sequiturs. With a certain Tourette’s Syndrome provocation, they tell us that, in point of cultural fact and desiderata, girls are not passive and, in turn, women are not naturally nurturing. By contrast, Dill’s work is largely airy. It’s potential comes with its use of text, in works like Still where the words 'faith' and 'guillotine' clash with thunderous conceptual reverberation. However, this potentiality goes quickly exhausted as it is overcome in other pieces by her literalist use of body parts. Once again the work verges on the derivative, bringing to mind the much better articulated work of Kiki Smith. What’s missing from Dill’s body-work is Smith’s visceral fleshiness, a corporeal presence that verges on the obscene in works such as Smith’s Untitled (Train) (1994). A waxen female nude with a stream of menstrual-hued beads running from between her legs, this piece by Smith is the full-blown embodiment of cunt-art. By comparison, cunt-art savoir-faire remains dormant in Dill’s sculpture.

Meehan and Gill’s work forces the question of the “feminine” and makes us ponder its values in the undergrowth of feminist politics.

Images courtesy the artist and The MAC.

Charissa N. Terranova is an Associate Proffessor at SMU and a Contributing Editor to Glasstire.