San Antonio’s art community has a witty sense of space. Recycling commercial spaces for uses far off the original mark is almost a hallmark.

San Antonio’s art community has a witty sense of space. Recycling commercial spaces for uses far off the original mark is almost a hallmark. Artpace resides in an old Hudson automobile dealership, the Southwest School of Art & Craft was the Ursuline Academy and Convent, Blue Star Contemporary Art Center was a 1920s warehouse, and the San Antonio Museum of Art was a brewery.

A number of San Antonio artists, either alone or in pairs, have acquired commercial buildings for mixed use as well. They live with, make, and exhibit art in these spaces. This is the first of a two-part series of articles featuring some of these interesting chop shops, repair shops, tortilla factories, grocery stores, and warehouses-turned-homes. Each building with its distinctive inhabitants provides a colorful example of creativity running amuck over thousands of square feet.

One of the most fundamental characteristics of a healthy art community is affordable housing, the lack of which pinches cities like New York, Seattle, Los Angeles and San Francisco. Art scenes will flourish there anyway, but a feeling of community is often absent. San Antonio’s artists, on the other hand, have enjoyed a better housing market and have thrived for it.

The Bettie Ward Studio inhabits the corner of Avenue E and Brooklyn, just off Broadway’s North-South thoroughfare. A bubbly sign hangs out front, just around the corner from the homey, fenced-in patio area, ringed with cactuses and dotted with potted plants. Take a good look at the building behind these decorative accoutrements, however, and it is recognizable as a 1930s automotive shop. Originally called Nix Alignment Service, the building is graced with large doorways and an Art Deco feel. The masculine aspects have been mollified by its female inhabitant, artist Bettie Ward, who bought the building eight years ago.

Ward was a mother of three, unexpectedly single and living in affluent Alamo Heights, when she turned to art as a career. She had loved art history in high school, especially the descriptions of bohemian lifestyles and artists’ garrets, and had worked with Native American artists in New Mexico in the 1970s. As part of her training, she enrolled in the San Antonio Art Institute, then on the grounds of the McNay Art Museum. Specializing in sculpture, her teachers included Bill FitzGibbons, who is currently the director of Blue Star.

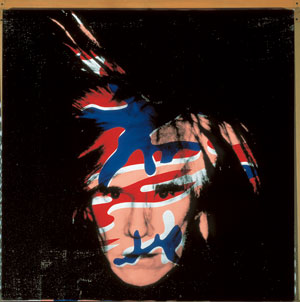

After she left the Institute in 1991, she switched her focus to painting. Ward, who mixes many of her own paints, developed a dry pigment process that produces a signature powdery texture, like thick pastel. She has rented studios all over San Antonio and remembers, less than fondly, rescuing paintings from studio floods during rainstorms. Then a friend told her about a vintage automotive shop, then basically just a shell, on the north side of downtown. She bought the building, eventually selling her Alamo Heights home.

The building stands just off Broadway in an area called Irish Flats, named for Irish settlers’ flat-roofed homes. Ward got the building into shape, fixing something on the building each time she sold a piece of art. She officially moved into the remodeled space in 2002. Today, the 4,000-square-foot building contains Ward’s living area, frame shop, office, and studio space — both a room for flat paper work and a large area for painting. Two Standard Poodles, Paris and Romeo, roam the place like 1950s figurines woken from porcelain slumber. The décor is an eclectic mix of Asian and Mexican objects, antique furniture, Ward’s artwork, and old family photographs. Her decorating is similar to her paintings in the striking use of bold color and texture.

There have been continual changes to the building and she uses salvaged material whenever possible. Ward’s white ceiling is really quilted insulation — Robert Ryman meets Barnum & Bailey. The garage doors proved challenging to insulation, security, and the prevention of dust, so only one garage door remains. Today, a set of Isaac Maxwell doors are installed in one of the doorways. Maxwell, famous for his lamps of tin, copper, and brass, made these pounded doors of mixed metals that add to the luster and texture of the studio.

San Antonio artists, no matter where they live, are known for throwing their homes and yards open to friends. Ward opens her space for the occasional exhibition as well as events, most recently a “Friendraiser” for mayoral candidate Phil Hardberger, who has declared his support of the arts. The event featured local favorite dish Frito pie and drew a crowd of 300 people.

On the other side of downtown from Ward’s place, Southtown continues to be a central spot for artists to live, drink, and even marry. Katie Pell and Peter Zubiate live and work in a 1930s former grocery store on Labor Street. Pell and Zubiate, who met during simultaneous art residencies in Aspen, Colorado in 1993, moved to San Antonio nine years ago. Working odd jobs and forging art careers in a new town, Pell and Zubiate painted rodeo signs, arranged flowers, and did carpentry for a while. They had a studio across from what is now Cafe Revolucion. Eventually, Oscar Alvarado, whom Pell calls “Mr. San Antonio History,” told them about the Labor Street building and motivated them to buy it. They purchased it on a shoestring budget.

The modernist building’s varied history includes a 1930s grocery store (the original butcher case was still intact when the artists bought it), a Chinese grocery, and the Labor Street Barber Shop in the 1970s. Just before Pell and Zubiate moved in it was a deliciously illicit automotive chop shop. Strangers coming by looking for their cars were not uncommon occurrences for the couple. Neither were drug dealers, whom the two simply informed that operations out front were now closed.

Though the couple bought the building in 1998, they lived elsewhere and worked on the raw space for a year and a half. They finally moved in and, as a confluence of events, Pell delivered their daughter Bygoe there, despite the building’s still being a virtual shell and the cold of February pouring in. Bygoe is five now, and her presence is felt everywhere, from the pink of the chicken coop out back, to the plastic rocking horse in the yard. The three live in an artistic laboratory where fancies are given free reign.

Peter Zubiate is an art furniture maker from a longstanding Marfa, TX family. His grandfather was a bricklayer, his father is a furniture maker and antiques restorer, and his uncles have run watering holes in Marfa for years. Peter makes streamlined furniture with interesting appendages. His original designs were featured last year in a solo show at the Southwest School of Art & Craft. Sometimes people get confused — is it furniture or is it art?

Katie Pell has lived all across America. Originally from Delaware, she studied painting at Rhode Island School of Design. As an artist, she needs two studio spaces — she earns a living through ceramics but her processes of choice are drawing and painting. While living in Seattle, she assisted glass artists and expected to do something similar in San Antonio. Realizing her new town did not have a studio assistant system to speak of, if she wanted a stable art career she had to devise a new plan. Pell remembered experimenting with pottery while in Aspen and selling those pieces. She made a choice to pick it up again threw herself into it as a home-based business.

The couple’s building, with “Shrimp” still painted on a front window, rambles between open living spaces and rambling studios with few dividing walls. Their kitchen is large, with a long table by Zubiate as central focus. On the other side of the swinging doors is Zubiate’s large wood shop, which in turn opens onto Pell’s work spaces.

Currently the couple is carving out a second-story bedroom. A newly acquired spiral staircase winds its way up, somewhat treacherously, to their future master boudoir. The couple acquired the metal staircase from fellow artist Riley Robinson, who years ago salvaged it, took it apart, and stored it under his mother’s porch in Maryland. Pell and Zubiate dragged it out, piece by heavy piece, and drove it to San Antonio.

The back of their building has been cleared of former sidewalks, bathrooms, and showers and replaced with an ecosystem. A compost pile quietly decomposes in the backyard, while their chicken coop brightens the yard’s corner, providing them with fresh eggs. Pell’s ceramics are strewn throughout, as are Bygoe’s toys, giving it extra texture and color.

Pell is aware of the fascinating story behind artist’s studios, many of which are within walking or biking distance of their own home. For the fourth year now, she is coordinating the Automatic Studio Tour during Contemporary Art Month. It’s an event that gets the extended neighborhood walking, talking, and greeting each other.

Each artist space is different, run a different way, with a different set of goals. The Triangle Project Space, for example, currently on hiatus during its relocation, has received a lot of critical attention as an independent art space. TPS is run by artist Luz María Sánchez and artist/furniture designer Peter Glassford. The couple met in Guadalajara, Mexico where Sánchez worked at a radio station and Glassford was creating a multi-national furniture business.

So early in 2002, a World War I-era gas station and mechanic shop was spotted. It sits on one of those corners that carve city blocks to a point. It was, essentially, a triangle. In the late nineties, Brent Widen invited Peter Glassford and some other friends to buy the Triangle Building all together. By the end of 2002 The Triangle Building got transformed by Sánchez and Glassford in their innovative renovations and in the summer of 2003 the Triangle Project Space (TPS) was born.

People who have moved into aged commercial buildings have similar stories to tell — no storage, ancient, smelly stains on the floor, and lack of temperature control, to name just a few special highlights. Sánchez and Glassford slept on a mattress on the floor for a year and ate off a hotplate donated by friend and fellow artist Guy Hundere. They, like Pell and Zubiate, also lived, worked, and developed their visions in close quarters with their partner.

TPS began in an open space that, as it piggybacked on the furniture business, was at risk of giving way to a furniture showroom at any moment. The two found creative solutions to shape a flexible, mixed-use area. Nearly everything was on wheels, including the kitchen. Temporary exhibition walls were built with storage space inside.

The space continued to take shape as the couple hired friends to build them walls, a stage-like kitchen floor, and a massive sitting area. To put it crassly, the contemporary, floating atmosphere resembled an Austin Powers shag palace. Often, people would come to see art and be more interested in the building’s interior.

While locals helped the construction of the gallery, the space shows art by emerging artists from a range of international locations, from Latin America and to the Middle East. Their first show in the summer of 2003 featured Spanish photographer Anna Ferrer’s The Emotional City. Sanchez promotes TPS with European institutions and artists, but says it’s from a series of “collisions” that the space culls its artists. Sanchez sees it as a way to encourage the growth of San Antonio as a non-insulated art scene with an exchange of ideas. The coupled designed TPS as a laboratory. They give emerging artists the chance to create art without worrying about its commercial value, and tend to focus on what their website calls “media driven aesthetics,” such as video and sound work.

Sanchez, a trained pianist finishing her Masters degree in art history at the Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, is interested in sound as form. At the radio station in Guadalajara she was a disc jockey, newscaster, producer, and assistant director. Her thesis topic, Samuel Beckett’s radio plays, expands this interest in audio art. So it was no surprise that she brought Sound Site to TPS last year. Manuel Rocha Iturbide, curator of the International Sound Art Festival in Mexico City, coordinated the show. Another such show will be coming to their new space when exhibitions resume.

Triangle Project Space is now in the process of moving locations, so the couple have begun renovating an even larger, even rawer space — another mechanic shop. Again, it will be a “fluid convergence of business and culture.” Glassford can close his warehouse in Dallas and store stock in the new 15,000 square foot building. His office is already in shape, and he recently rediscovered his original chair design, which holds pride of place amongst more current designs. The business recently bought the former warehouse studio spaces next door, adding to their art and design empire.

Bettie Ward, Katie Pell and Peter Zubiate, and Maria Luz Sanchez and Peter Glassford just scratch the surface of what lies behind “shrimp” windows and garage doors in San Antonio. In the next installment, I will continue to unravel the tale of San Antonio’s vintage commercial buildings and the artists who love them.