Works of extreme creativity, the stuff of cultural and political revolutions, are what keep history from being a dull, slow hum.

Until mid-twentieth century, Paris was arguably the densest center of Western culture. It was a site for émigrés from the East, the Lost Generation of young Americans, and Latin American artists and writers. The compression of people with fresh ideas into a set of city limits erupted into controversial monuments and events.

What earned France, and Paris as its masthead, its modern stripes as a cultural icon was the French Revolution, begun in 1789. During our mutual eras of revolutions, France and young America were like kids gone off to college — just enlightened enough to be dangerous. First we, and then they, shirked off repressive dictatorial monarchies who cared little for the lower classes.

In his exhibition Flaternité at Finesilver Gallery, Hills Snyder, local prestidigitator of witticisms, brings France to the fore. The exhibition’s name puns on liberté, fraternité, egalité, the French Revolution’s democratic buzzwords. Snyder’s twist refers to his use of flat Plexiglas cut to shape and laid flush with the wall. With clean shapes and elegant material, Snyder’s works crescendo from bon mots to current world events.

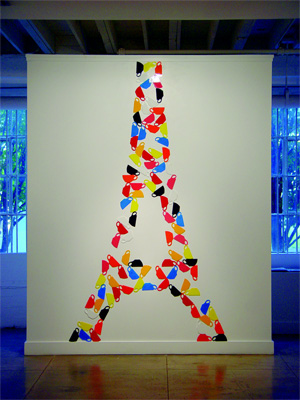

Upon entering the gallery, an Eiffel Tower made up of topsy-turvy tea cups looms up on the facing wall. Titled Out of Breath and Wild, the work flickers with various candy colors of pink, blue, orange, red, white, and black. Its title recalls an idealistic Audrey Hepburn singing on top of the tower in Funny Face, arms thrown wide in an ecstatic embrace of Paris.

The buoyant uplift of the smaller shapes into that familiar icon is charmant, but the Eiffel Tower was originally despised by the citizen ants milling below and climbing up its naked steel beams to get to their café au laits. (Original ants of note include the Shaw of Persia, King of Siam, and Buffalo Bill.) Built as a scientific tower in 1889, its past controversy mirrors that of our offshore wind generators and faux-tree cell towers today that also allegedly mar their environments.

On the facing wall is a white clawfoot bathtub, Site, again cut from solid-colored plastic sheets and fixed to the wall. Rather than resting on the floor, it sits on the base board like a sculpture on an absurdly narrow pedestal. Perfectly round, red circles pockmark the tub’s whiteness. They transform the tub from simple object to the possible site of Charlotte Corday’s assassination of Jean-Paul Marat, fiery Jacobin orator and editor-in-chief of L’Ami du Peuple, in 1793. Marat, who had a skin condition that required him to spend many hours a day in his bathtub, was a captive victim to her stabbing. The painter Jacques Louis David, a personal friend of Marat, captured the most famous image of the assassination that same year.

David, a painter of historical scenes, was active in the reign of terror and voted for Louis XVI’s execution. The blood on his hands extended to at least 300 other executions for which historians have shown he signed orders. While David strove to topple the political hierarchy, he proudly painted at the upper rung of painting’s genres. Historical paintings were considered the most important works of art, while still-lifes dwelled in the lowest echelon. David’s propagandist works included the Oath of the Horatii and the Death of Socrates. In a modern twist, Snyder has continued the tradition of historical subjects, but he does it through single objects — the Eiffel Tower, a bucket, guillotines — that are, in a sense, still-lifes.

Bouquet, a piece poised on top of a doorway, looks like a blown-up version of the “water on the knee” pail from the game Operation. Snyder achieves elegant minimalism by layering white plastic against white wall. The piece refers to a comical play on words — “bouquet” being mispronounced as “bucket” (not to mention the whole “merci buckets” quip). Its location at the top edge of a doorway extends the humorous reference, as if it was part of that age-old gag where someone opens the door and gets a bucket of water on the head.

Hills Synder... Double Lunette... 2001... 120 x 43 x 1 inch acrylic sheet, birch support and wall cutouts

Snyder in real life is a constant punner, an amusement he shares with French artist Marcel Duchamp whose titles are often complicated auditory puns. Whatever the case, Bouquet is like a refreshing candy pastil, a break from the larger historical references in the exhibition.

The two most dramatic works on view are 10-foot tall guillotines. Snyder fitted together red, blue, and yellow plastic shapes against white wall for Back to Basics. The colors recall Piet Mondrian’s squares of color, but the very un-Mondrian diagonal of the guillotine’s yellow “blade” cuts through the similarity. Snyder bore a hole through the wall where a prostrate neck would be held in place. The tall, slender height of the piece adds a visual momentum as one imagines the blade dropping. Again, Snyder’s subjects have alternative histories. What we as modern viewers see as killing machines were invented as a more humane form of execution.

On the opposite wall is one of the most understated and elegant of Snyders’ works. Double Lunette is a guillotine with twice the killing parts. White supports, a pink translucent blade, and reflecting silver give off a ghostly pallor. This time the holes are filled with fluffy pink insulation, reminiscent of bloody stumps but without the gore. The work is spare and gaunt, and frankly should be collected by a museum.

Gesture: Edition Endless is a quiet piece that breaks with the continuity of plastic material. Here Snyder incised a ribbon shape into the drywall, with white, powdery dust left fallen on the floor below. The colorless ribbon is familiar as the yellow ribbons that ask us to remember our soldiers. In this version, though, rather than following the sticker on the back of the car in front of you, both of you burning through the petroleum that keeps the wars going, Snyder has a more productive gesture. When you purchase the piece, Snyder gives the $250 purchase prize to Halo Trust, an organization that “specializes in the removal of the debris of war.” This is a final, positive gesture on the part of the artist and collectors, and extends his work from history into another kind of revolutionary ideal.