There is a ripple going through the San Antonio art community. It’s the appreciative buzz that comes with a young artist who awes not just his elders, but his peers as well.

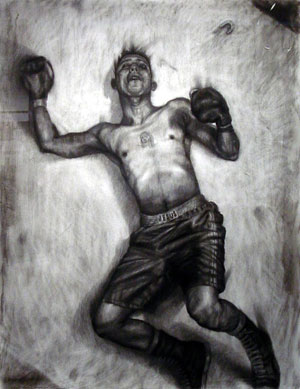

Vincent Valdez... III: Main Event... 2004... Charcoal on paper, 92 x 42 in.... Collection of the artist

Vincent Valdez’s solo exhibition Stations at San Antonio’s McNay Art Museum is one of those impressive, near perfect exhibitions of finely-tailored work.

The intimate gallery is chockablock with large-scale charcoal drawings in hearty black frames. Depicting the last day, and fight, of a boxer’s life, Valdez based his series loosely on the Stations of the Cross, or the last moments in Jesus’ life, which include his taking up the cross, falling, and dying. Physically, the corners of the gallery have been rounded by panels, suggesting the circular face of a clock and the cyclical nature of birth, death and rebirth. Roman numerals applied to the walls tick off the stations, again reminding one of the hours and moments of a single day. Viewers, rather than arms, sweep around the room from work to work. As a side note to visitors, due to the gallery’s physical limitations, the drawings are hung slightly out of sequence, starting with the final image. Since it couldn’t be avoided, call it non-linear time and just enjoy.

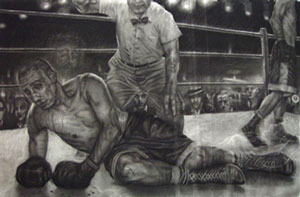

Artists have represented the Stations in various forms for centuries. Carol Kino, essayist for the exhibition’s catalogue, names Giotto, Pablo Picasso, and Stanley Spencer as artists who interpreted Jesus as an everyman in his last moments. Just last year another San Antonio artist, Katie Pell, used the theme in a series of photographs at Three Walls that used gas stations as backdrops to emphasize a feeling of commonality. Valdez associated his boxer with the Stations only after recognizing that there were similarities in the stories of tragic heroes who die ignominiously. Two of his initial studies, They Say Every Man Must Fall and He Then Fell Once More, are now part of the series. Despite the show’s obvious religious subtext in its title and layout, Valdez avoids a direct correlation by limiting the number of stations to 10 (versus the traditional 14 in Catholicism), and avoiding overly literal associations.

Vincent Valdez... VI: They Say Every Man Must Fall... 2002... Charcoal on paper, 42 x 60 inches... Collection of Jorge Elizondo, San Antonio, Texas

The first station, Weigh In: Coming in at 140 lbs 8 oz, is a masterful scene with life-sized figures. Light from a half-window cuts through cigar smoke. Eroding posters proclaim “Kind of the Ring”. Four men encircle the boxer with rapt attention to his every detail as they measure his weight and heart rate. Even inanimate objects seem enthralled by him — a microphone leans in to catch any of the athlete’s potential utterances. The quality of the drawing is such that you have to move in close and, as a result, the viewer completes the circle of attentive onlookers, studying the realism of the boxer’s face with equally rapt amazement. While abstraction and minimalism sent figurative art into (at best) a corner for years, Valdez is one of those young artists ensuring the comeback of the narrative image. Ironically, minimalism’s finish fetish and attention to the innate beauty of material is present in the artist’s powdery, lush charcoal workings.

The second station, The Strongest Man in the World is He Who Walks Alone, tips the tight, vertical format over into a panoramic view of the boxer, face nearly hidden by his hooded jacket, walking through the stadium crowd. This boxer is always entirely alone, even when surrounded. Valdez uses scale, lighting, and other compositional devices to cloak his boxer in solitude in each of the drawings. As a foil, Valdez used his brother, Daniel, as the model for his central character; and the artist cheekily includes his own friends and family in the crowd, including a self-portrait and a portrait of his art dealer, Finesilver Gallery’s Chris Erck, chatting on a cell phone.

In Main Event, things turn serious as the boxer, suddenly hoodless, confronts the viewer as he confronts his opponent in the ring. His gloved hands, feet, even his baggy shorts, are enormous. He is a formidable opponent, his head ringed with a halo of lights. The canvas of his body is built up by crosshatched lines, with blank areas of the textured paper alternating with heavily worked areas and frenetic markings. Highlights overlap and liquefy dark outlines.

Vincent Valdez... V: He Then Fell Once More... 2002... Charcoal on paper, 60 x 42 inches... Collection of Bill Colburn, Houston, TX

Rounds of the fight ensue, showing the boxer increasingly bloodied and bruised, yet contemplative. In seventh station, the boxer gets knocked out for the last time. Valdez breaks this important moment up into four drawings, an effect similar to the slowing of time just before a car accident. The last of the four is an empathetically dizzying view of the boxer crumpling to the floor of an upended ring. In Laid Out, the ninth station, the body lays lifeless on a table, a preview to his funeral. The viewer again participates, this time in the position of an onlooker or mourner.

The final scene, Collect ‘Em All, seems strangely out of scale. The boxer is smaller and set against a background covered with abstract swathes of charcoal shading. Light seems to burn from his shoulders and chest as he puts up his fists. The title’s suggestion of trading cards plays on the collection of images on view, and this additional resurrected soul which Christ, who appears numerous times through the series, as a tattoo, wall graffiti and ghostly presence, collects through salvation.

Lyle Williams, Curator of Prints and Drawings at the McNay and curator of the exhibition, has an office that abuts the gallery with clear glass doors. He makes a quiet statement about the importance and timelessness of Valdez’s drawings by hanging another framed boxing scene where viewers can see it — it’s a classic George Bellows. The quality of Valdez’s works, whose manly subjects look as if they could have been made from cigar ashes, is a poignant comparison to this classic Ashcan School painter. Valdez’s Stations may just stand the test of time.

Images courtesy the artist and Finesilver Gallery.

Catherine Walworth is a writer living in San Antonio.