As one of the final exhibitions at Inman Gallery’s Travis space before the gallery’s move to its new location in the Isabella Court building on Main Street, Bill Davenport has aptly drawn the era to a close with his latest “book” paintings.

Wry yet sensitive, these six new paintings simultaneously evoke a sense of nostalgia along with an impression of the present moment. The images — mainly realistic depictions of books, animals, ephemera, and random objects — function both as self-portraiture and a study into the techniques of painting itself.

Utilizing books from his own collection as the primary subject matter (along with realistically-rendered personal mementos such as a snapshot of a pet and a grandmotherly-looking envelope addressed to his son Phineas), Davenport allows insights into his varied interests, and shares what is most important to him. This glimpse into his psyche is somewhat subsumed by the paintings’ compelling compositions, as Davenport’s images change stylistically from painting to painting, often based on the content or design of one or more of the books illustrated. Despite this exploration of various styles of painting — including abstraction, photo realism, and Dutch still life painting — all the images relate. Davenport handles each canvas with a sure, confident hand, and each painting is exquisitely executed. As a whole, the works are united not only in their craftsmanship, but also in Davenport’s humorous selection of objects and their unique juxtapositions.

Reminiscent of seventeenth century gaming imagery, one of Davenport’s most recent paintings, Dead Ducks (2004), depicts a page from the Irish Independent newspaper, a draftsman’s triangle, a ruler, an envelope addressed to his young son, the molding from an empty picture frame, a business card with a handwritten note, and a grouping of four dead ducks all tacked to a green wooden door. The space is collapsed and compressed, but in the tradition of still lifes viewed straight-on (such as John Haberle’s Can You Break a Five?, 1885, from the Amon Carter Museum collection in Fort Worth), this trompe l’oeil is so well executed as to suggest that these objects actually are tacked to the wall in front of the viewer. Several of the background elements, such as the newspaper with its headlines profiling Ian Malone, UK soldier and reporting that “we all…have sex without regrets,” as well as the envelope, are so realistically rendered that at first glance the work appears to be part collage. The dead ducks themselves are painted in a looser manner, and their feathers, plush and ruffled, are more expressionistic in technique. Pulling together objects with various surfaces — hard wood, feathers, paper — with meticulous detail to each, again demonstrates Davenport’s interest in blending different stylistic elements all in one canvas.

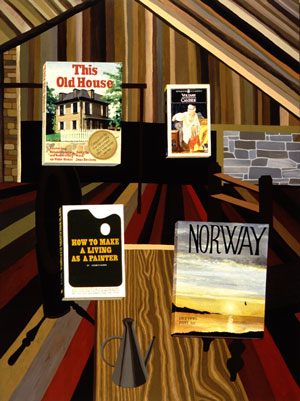

This Old House (2004), the other painting from this year, is more consistent in content and design, not only with the other works in the exhibition but also some of Davenport’s prior works. On this canvas he plays with a deep space in which the objects seem to float. Four books: a companion publication to the PBS series This Old House, Voltaire’s novel Candide, a self-help guide on How to Make a Living as a Painter, and a photo book of Norway seem to rise up off the foreshortened table. The books (painted in a realist manner) along with a container resembling a pitcher or an oil can are front and center of the canvas, in contrast to the orthogonal lines of the floor boards and the sloping, angled paneled ceiling that suggests an attic room. Playing off of the content of the books, the room appears to be part of an older house; the wood is mixed with brick and stone walls. Perhaps this is the artist’s studio as related to How to Make a Living as a Painter? Perhaps just an Old House, as Davenport dexterously plays a game not only with the eye, but also with the mind.

His canvases can function in the manner of trompe l’oeil, yet the amount of information he provides is deceiving. Davenport teases his viewers with hints into his thoughts and concerns (is his son, like the UK soldier, a “dead duck” in a world smothered by the feminine, or sexual, principle?) — but he cleverly never gives the game away, a wry reminder that the viewer not read too much into these quirky amalgamations of real-life and imaginary tableaus.

Images courtesy the artist and Inman Gallery.

Jennifer Jankauskas is an independent curator and writer living in San Antonio.