The screen door just inside the entrance to Barry Whistler Gallery makes you want to peer in with your hands cupped around your eyes. At the far end of the corridor, a diamond-shaped mirror reflects you as you look.

This house may be haunted, but you go in anyway. Moving so quickly from bright sunlight to almost complete darkness is disorienting, so you walk down the corridor slowly, turning left into Michael C. McMillen’s installation entitled Time Below.

Now you’re disoriented again. The scene depicted is obviously from an aerial perspective. A toy rail line stretches diagonally across a landscape. Its abstractness is calming to some extent. Monochromatic earth tones are a psychologically stabilizing force to most people. At distances away from the rail’s station there is an oil derrick surrounded by outsized trees that casts fingered shadows on the matte brown walls. Farther away are geometric abstractions of houses, cars, barns and sheds. The objects grow smaller the farther they are from the central illumination.As your eyes adjust to the dimly lit room, you can barely make out a bench to sit on in the center of the room. Movie time, you think. The soundtrack is so minimal that you hardly notice it at first. Out in the middle of nowhere is the chaotic sound of Locusta migratoria. A blues singer fades in occasionally.

An additional element of the installation becomes evident as you look. The light is changing ever so slowly, making the long shadows of the faux trees shift on the wall ominously. The slow pendulum hanging from the ceiling fits in with the railroad theme. The air begins to leave the room. You begins to wish you could crash the plane you’re in. Maybe it will run out of gas.

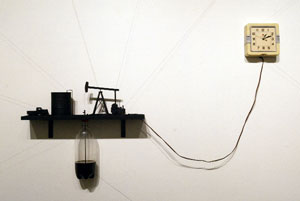

Michael C. McMillen... Illustration (Nature Morte), 2004... Wall installation (used motor oil, Coca-Cola bottle, electric clock, tin can, oil pump, paint, toy truck and thread)

This last is exactly what the artist wants you to think. The illusionism is of cinematic origin and turns theatrical when being explained. On display outside the installation is a sculpture called Illustration. Another oil derrick is meticulously crafted on the wall. An old clock is placed with the cord running to the derrick. Connected to the pump beneath the derrick is a large plastic Coke bottle filled with black sump oil. Wires radiate out with dates affixed…dates obviously associated with the oil industry. This sculpture spells it all out, too clearly; and the closed-down nature of the dialogue saps the energy of the more graceful ennui that can be felt in the brown room behind the screen door. The oil is running out, kids. Run. It’s later than you think.

This piece is a blues song, and it’s true that it’s later than you think — but not any later than it’s ever been. That said, McMillan is a heavyweight when it comes to craft. He has worked on some of the great miniatures, including those from Close Encounters of the Third Kind and Blade Runner. With Time Below, one is forced to admit that he is skillful; but despite the piece’s craftsmanship and the obvious sincerity of its message, one wishes the work to be more poetic in the strong sense of the word: a moving front of anxiety that surpasses the illustration. In installation art, a conflict often manifests between the meditative and contemplative. McMillan’s meditative installation (the dark room) coupled with its subsequent illustration (the wall sculpture) tends to factor out complexity, then stridently claims to be an “open ended narrative.” In a purposefully ambiguous narrative, the voids must be carefully placed so as to cause us to contemplate something more complex than surface reality. The meditative, applied to the problems of our shared actual world, is always in danger of lulling the viewer into a false sense of security about what is really dangerous. The conflict between the real and the actual mixes in our ears as we try to get back to sleep. A depopulated world is what this work pines for beneath its oily slickness, and that is perhaps why the house is truly haunted.

Images courtesy the artist and Barry Whistler Gallery

Mark Babcock is an artist and writer living and working in Dallas.