Walking into the spacious gallery of the Blaffer when it’s filled with people can be intimidating.

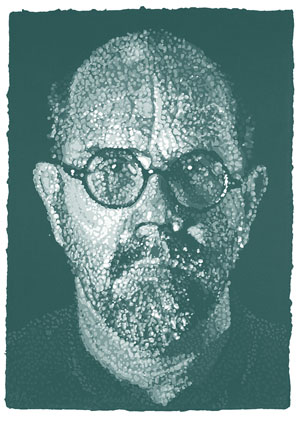

Chuck Close, Self-Portrait/Pulp, 2001... Stenciled handmade paper pulp in 11 grays. ... 57 1/2 x 40 inches. Edition of 35.

In the case of Chuck Close Prints, however, it feels like you’re joining a party (albeit a somber one), with Keith (Hollingworth), Alex (Katz), Phil (Glass), Chuck (Close), and some less well-known friends and family of the artist. The faces look right at you, locking gazes; yet they are engaging and familiar rather than confrontational. The various “heads,” as Close has termed them, bleed and blur into new expressions as a result of the artist’s explorations of different print processes. He creates a multitude out of a few while still retaining an accurate likeness of each, making them recognizable. Our familiarity with Close’s sitters is partly a result of his archive of stock faces that he uses habitually throughout his work. He pulls from this inventory of images, irrespective of the time the photographs were taken, to reinterpret the same likeness over and over with different processes. Does familiarity breed contempt? Not at all; instead it provides an atmosphere where the people portrayed become accessible (without necessarily providing any insights into their personalities), allowing for an exploration into Close’s thoughts and artistic practices.

Chuck Close Prints: Process and Collaboration, curated by the Blaffer’s Director, Terrie Sultan, is aptly named. With a hefty 118 prints, this exhibition is a visual investigation into Close’s long history with printmaking. Working for over thirty years in various print media — mezzotint, lithography, screen printing, etching, aquatint, linocut, and woodcut, as well as adapting some techniques of his own — Close has consistently tackled, mastered, and ingenuously pushed the boundaries of each process, in some cases returning long-neglected forms of printmaking to prominence. In doing so, he has had to rely on the expertise of many master printers to teach and assist him in completing each work. Forming relationships based on trust, the relinquishment of control, and a real brainstorming of creative ideas has resulted in unusually rich investigations into editioned work. As the first full-scale retrospective to focus exclusively on his prints, this exhibit presents not only is a diverse body of work, but draws corollaries between Close’s printmaking to his better known paintings and photographs, all of which illustrate the cyclical nature of his methods and practices.

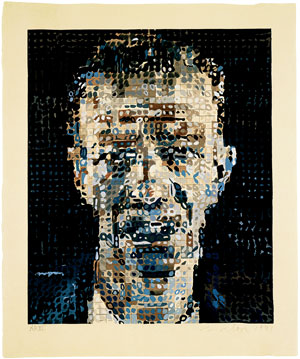

Chuck Close, Alex, 1991... 95-color Japanese-style ukiyo-e woodcut... 28 x 23 1/4 inches. Edition of 75...Keiji Shinohara and Bruce Crownover, Malden, Massachusetts, printers

While working methodically, Close reacts well to experimentation, accident, and serendipity — one of the most imposing and detailed works is Alex/Reduction Block (1993), a silkscreen that was originally intended to be a reduction linocut. Problems with both the paper and the linoleum block called for rethinking how to complete the project. Close and his printers (Bill Weege and Joe Wilfer at Tandem Press and Robert Blanton and Thomas Little at Brand X Editions) inventively crossed the boundaries of two distinct processes, yielding an unusual and gorgeous final image with a richly detailed, luminous, imposing presence. Hung next to this spectacular image are seven progressive and state proofs.

Close’s first foray into printmaking, another experiment called Keith/Mezzotint (1972), opens the exhibition. Mezzotint, a half-forgotten process of etching invented in the 17th century and widely utilized during the 18th and 19th centuries, was resurrected by Close and master printer Kathan Brown, both of whom had to learn the process. This experimentation called for repeated proofs to be made as they tried different techniques. The area where most of the proofs were pulled — around the lips and nose — wore down, exposing in the final print Close’s mechanism of the grid structure. The artist’s embrace of this anomaly became a key element in his future work, and after this point Close no longer disguised the incremental building units that are essential to his prints and paintings. As the largest mezzotint ever created, Keith/Mezzotint perfectly symbolizes the thrust of both the exhibition and Close’s career in printmaking.

Emma, 2002 is Close’s most recent print in the show. Taking nearly three years to complete and featuring 113 colors, this Japanese-style ukiyo-e woodblock relates Close’s rationale in producing an edition. Though extremely time consuming, Close insists that all his prints are handmade, not just purely reproductions, which allows for individuation. Each bold, swirling mark of color in Emma exactly mimics those seen in Close’s painting of the same title (included in the exhibition for comparison), as master printer Yasu Shibata painstakingly matched each of the notations in shape and hue to the painting. Yet the print, so like the painting in design, has a graceful lightness and transparency not seen in the original.

Chuck Close, Emma, 2002... 113-color Japanese-style ukiyo-e woodcut ... 43 x 35 inches. Edition of 55... Pace Editions Ink, New York, printer (Yasu Shibata)

Also exciting to see are the other unusual processes that Close has explored. The early pulp paper multiple Self-Portrait, Manipulated, 1982 relies heavily on Close’s signature grid. Soon, however, Close broke free of that structure to collage paper pulp chips into the head of his daughter, Georgia, 1982. That piece spawned a much more abstract and sculptural variation, Georgia, 1984, and opened Close to a new arsenal of tactics with paper, which he exploited with the 2001 Self-Portrait/Pulp where his likeness is stippled in eleven different grays. Here, the subtle gradient shift of light to dark allows for surprising depth in this two-dimensional format. Another recent project, a portfolio that includes proofs as well as a final image as a way to demystify his process, is another example of pushing the boundaries of a printmaking process. He has utilized more plates, layering up to nine colors in his scribble etchings. With Self-Portrait/Scribble/Etching Portfolio, 2000, Close doodles in various colors—one at a time—as a way to build up his image. It is with this process that he has come full circle, finally removing the grid underlying all of his previous imagery and finding an alternate substructure with the shortened lines.

The breadth of the installation not only shows Close’s inexhaustible capacity for invention but also details his development as a printmaker with an array of proofs and final prints in multiple processes along with several vitrines filled with notes, color charts, and sketches for works. The prints parallel Close’s maturation as a painter and demonstrate his equal love of this medium. Although the exhibition focuses on only one aspect of his artistic output, the viewer can fully grasp Close’s entire body of work as his explorations into printmaking collapse into various meditations that become manifest in all his processes.

Images courtesy the artist and Blaffer Gallery.

Jennifer Jankauskas is an independent curator and writer living in San Antonio.