The UBS PaineWebber collection numbers well over 800 works, and features some of the best-known artists active from the 1950s to the present.

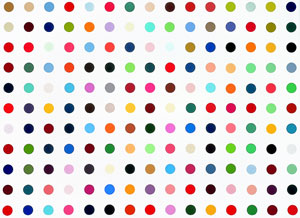

The focus is surprisingly broad, spanning nationality, media, and approach. Among those included are Chuck Close, Damien Hirst, Anselm Kiefer, Roy Lichtenstein, Lorna Simpson, Thomas Struth, and Andy Warhol, to name but a few. Many artists are represented by more than one work and the collection boasts strong holdings in works on paper. A selection of paintings, photographs, and sculptures from the collection, organized by the Portland Museum of Art, is now on view in Embracing the Present: The UBS PaineWebber Collection at the Austin Museum of Art.

The basic principles guiding the collection’s founding and development are as significant as its specific contents. Donald B. Marron, former chairman and CEO of the global investment banking and asset management firm, initiated the collection in 1971 and is largely responsible for its growth over the last thirty years. Marron began collecting as a private individual in the early 1960s and is a long-time board member of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, currently serving as vice chairman. The UBS PaineWebber collection differs from that of a typical museum. It bears somewhat the stamp of Marron’s individual likes and dislikes, but is also very much a corporate collection. The focus is not merely art historical; according to Marron, the collection “began from the combination of my appreciation for art and the need to fill a sizeable amount of wall space.”(1) Contemporary art in particular became the focus, because of its reflection of current trends and potential to suggest the future. Marron selected work that he felt would challenge and inspire the employees to be open to new ideas and take risks. The collection has also turned out to be a savvy financial investment and a public relations asset.

The selection at AMOA well reflects the collection’s broad spectrum. There are a number of gems. Agnes Martin’s The Field (1966) produces its allure with an economy of means. Pale ink lines describe a simple grid, softly rippling the delicate, semi-translucent paper in their wake. Small points of graphite, setting the grid’s coordinates, reveal the process of its making. Alighiero Boetti’s large-scale Areo (1978) has a commanding presence. Scores of small airplanes float on a sea of undulating blue, obsessively inscribed in tight knit waves of ballpoint ink. Cy Twombly’s Untitled (1972) displays the artist’s characteristic, childlike scrawl. Enigmatic fragments emerge and dissolve across a creamy white surface, the words, “mythus” and “memory” providing a clue to the work’s meaning. Several pieces offer valuable counterpoints to better-known work. For example, Richard Long’s projects from the early 1960s exist mainly in the form of photo-textual documentation of walks or alterations of the landscape. Untitled (1987), a jumble of footprints captured in sandy-brown riverbed mud, records a performance, of sorts, enacted in the artist’s studio.

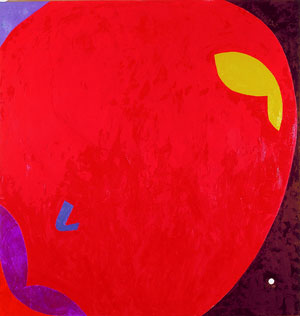

Elizabeth Murray, American, born 1940 ... Southern California, 1976 ... Oil on canvas 79 1/8 x 75 1/2 inches

Despite these attractions, the show is disappointing in several respects. For one, the work is overcrowded in the galleries, and the few sculptures seem out of place amongst the paintings and photographs. As is often the case with corporate or private collections, the work on view by big name artists is not necessarily their most interesting (neither Jasper Johns’s ULAE prints from the early 1960s, nor Edward Ruscha’s drawing Museum on Fire (1968), a study for his monumental painting The Los Angeles County Museum on Fire, are on view, though they are in the UBS collection). But this show’s overarching problem is the lack of a critical, art historical analysis. There is no real attempt at creating a framework for understanding the collection, its history, and its significance within the broader field of art and commerce. It is presented with seemingly little or no contextualization on the part of the Portland Museum of Art or AMOA. There is an introductory panel, but not much else. The rather strange exhibition brochure lists no author and was produced by Museums Magazines, an entity independent of the presenting institutions.

Without much input from the Portland Museum of Art, the exhibition bears an exceedingly strong imprint of the corporation that both supplied the work and made the show possible. AMOA’s presentation begs the question: have we come to a point where museums must outsource exhibition development to the highest bidder and if so, should we be concerned? We have already witnessed the emergence of edutainment, whereby education becomes adjunct to spectacle. If education is a component of a museum’s primary mission, as is the case with AMOA, any further sidelining of the curatorial function is definitely worrisome. Museums have a responsibility to present engaging programming, but also to provide a reflective voice. In this instance, the museums have gone mute and their galleries transformed into a billboard for hire. Embracing the Present thus reads as an advertising slogan: UBS PaineWebber is committed to “being on the pulse.”

1. Donald B. Marron, “Foreword,” in The PaineWebber Art Collection, (New York: Rizzoli International, 1994), 8.

Amy Dove is a writer living in Austin, Texas.