It was the time of Joe Ely’s Tornado Jam. My friends and I frequented a bar in Lubbock called Fat Dawg’s and jammed to Joe King, The Nelson’s, and whoever else was passing through. As I was poised at the bar one night, the great Lubbock native Bobby Keyes eased up, ordered a beer and sat down.

It was busy that night, but Bobby never had to wait in line for anything in Lubbock. Whenever he was within six feet of the bar, the bartender would stop and look at him and say “Bobby. . .?” I saw him there regularly for a while but only spoke to him once. Side by side in the head one night, I said “Bobby Keyes?”

“Yeah.”

“Big Fan.”

And I was. About forty seconds from the end of Can”t You Hear Me Knocking (which is a cool six and half minutes into it) he winds that sax around Keith Richards and it just blows me away. A great tune, a great band, the best ending to a rock song ever. Bobby Keyes was, of course, bigger than life. It seemed impossible that this person could be there at Fat Dawg’s, then, and also be a part of so many bigger things — I mean, THE STONES. He was a world of fantastic anecdotes, narratives, romance, music, and whatever. don’t get me wrong; I listened to Musta Notta Gotta Lotta everyday. I was a huge Ely fan, but it wasn’t just the music. Bobby carried a bigness with him. He was himself; He was simply Bobby Keyes. The great Bobby Keyes.

Which brings me to Terry Allen.

Another Lubbock native (born in Wichita, Kansas and raised in Lubbock), Terry Allen’s music was issued regularly over the waves when I was in high school. We all knew the words to Amarillo Highway, New Delhi Freight Train, and The Great Joe Bob, but it wasn’t until he was on the cover of Artnews in 1988 that I became aware of his art. Over the years I’ve seen exhibitions, pieces in collections, concerts, listings and even a few reviews, but Dugout, his current exhibition at Pillsbury Peters Fine Art in Dallas, is truly an exceptional event. The term “event” is appropriate because Dugout is much more than an installation or collection of pieces. It is a production. Moreover, it initiates a group of multi-media visual works, theatre/concert productions, and a publication or two that will evolve and propagate over the next two years to culminate at L.A. Louvre gallery, Los Angeles in 2004. Therefore, the production at Pillsbury Peters is a kick-off event, and in form with Allen’s standards, Dugout is loaded.

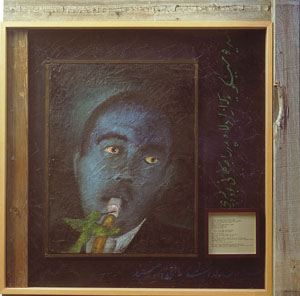

With a gallery sheet that lists six ‘stages,” five ‘sets” and total of forty-eight pieces, Dugout spills over and consumes most of the gallery spaces. Each area is presented as an installation with a common aural component. The framed pieces, which use text and images to illustrate a story, are installed butted up to one another. Images as simple and isolated as a car, a bruised and bloody hand, or a sex scene relate in some way to the ongoing story. The text blurbs are also somewhat isolated from one another; but again, related. The text and images maintain their autonomy but clearly flow as a narrative unit. Allen uses a variety of technical applications: wet media, pastel, graphite and others. The text component is varied as well, sometimes scrolled out by hand, sometimes stamped into soft metal. The more elaborate installations (or stages) involve fabricated interior spaces with chairs, neon, doors, windows, stuffed animals, dirt, trees, and so on. The story vignettes spoken by alternating voices over the speaker system bind the entire project.

Allen states: “Dugout is a made-up world, constructed and based on true stories and lies I heard as a boy growing up on the flat sprawl of West Texas. It is about baseball and music and a man and woman who play them both across the endless idea of America during the late 19th and first half of the 20th Century. It is a love story, an investigation into how memory is invented and a kind-of Supernatural Jazz Sport Historical Ghost Blood Fiction… with a little Jesus thrown into boot.”

The result is a densely layered set of contexts, narratives, and meanings that via the richness of their presentation attach themselves to the spectator as he or she engages with each element of this fabricated world. Although there is a common reference to “dugout” as it applies to baseball and plains domiciles, the word resounds as a shelter to protect the evolution of personal awareness and identity from itself, and from disheartening changes in the world around. Allen’s work often deals with issues of identity by using contextual shifts, such as lowbrow props in gallery settings or honky-tonk music in museums. Dugout, however, will offer more than the standard engagement fodder. This project in its current stage bombards the spectator/participant with information–visual, intellectual, and aural. Part of its power resides in the ability to evolve and reveal its destiny through time. Still, though Terry Allen and his wife Jo Harvey (“the world’s first woman Country & Western deejay”) will most likely be the only ones who experience every venue and production, anyone who spends a few moments in the gallery at Pillsbury Peters will understand the girth of this project and feel the weight of content as it oozes onto their shoulders from every direction.

I’m intrigued with the artist’s concern with the “America lost.” It is a compelling notion: we are all players in a world that necessarily alters ideals and ideas. A sense of moving through time and eventuality are strongholds of Allen’s artistic vision, and it is artistic vision that is on display. This vision is big, but it isn’t just the art. Allen carries a bigness with him. He is himself; He is simply Terry Allen. The great Terry Allen.

Images courtesy the artist and Pillsbury Peters Fine Art.

Johnny Robertson is a writer and artist living in Dallas, Texas.