For the first time since 1994, FotoFest returned to a thematic organization of its biennial citywide “festival” of photography. Previous themes have included Fashion, Contemporary Latin American Work, and The Global Environment. This year’s motif was “The Classical Eye and Beyond,” which may be looking at the festival through the wrong end of the microscope.

The majority of the exhibits organized by FotoFest concentrated on “new media” technologies, primarily digital work and video. To provide a historical antithesis, a handful of shows focused on work made in a classical style, i.e. fine-grain black and white photographs commonly using poor people as subjects, and making no advances or contributions to the photographic medium. The piously anachronistic was thus pitted against the precociously academic, and left most FotoFans caught in the middle without anything to sink their collective teeth into.

There is an older couple in town who pride themselves on having seen every single FotoFest-oriented exhibit since the mid-1990’s. I don’t know if this constitutes inspiring dedication to the local photography scene or a serious lack of critical judgment; but I imagine they have seen more than their fair share of stinkers, as well as some truly sublime exhibits that barely register a blip on the expansive FotoFest map. This artistic shroom-hunting can be exhausting, smelly, and ultimately, magically rewarding. During some high & low snooping this month, I stumbled upon a handful of terrific, small exhibitions that redeemed an otherwise bleak photographic landscape.

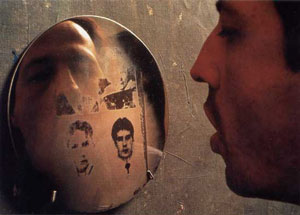

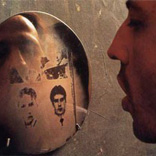

Out-of-town visitors to FotoFest speak of Sicardi Gallery in hushed reverential tones — this is because year after year, Maria Inez Sicardi presents stunning shows that consistently rival any exhibition citywide. She kept her torch burning this year, presenting new work by Colombian artist Oscar Muñoz. Muñoz’s work addresses the transient nature of images and memory. Many people walked right past Aliento (breath), the best piece in the show. A row of small circular mirrors lining the gallery wall at chest level appears to be an out-of-place post-minimalist gesture, but is actually a vessel of latent imagery. When one breathes heavily onto the piece and fogs the mirror, ghostly anonymous portraits appear, and then evaporate with the fleeting breath. I get goosebumps just writing about it now. In Narcisco, a delicate linear self-portrait was “drawn” on water using coal dust and a silkscreen. In the twelve photos and accompanying video, the floating, assured face of the artist gradually distorts and dissipates until it is completely lost in the water.

John Sparagana began work on his hauntingly-titled series I Wait For you Every Night on September 11, 2001, when too many smiling, seductive faces gazed up at him from a pile of magazines as he was turned away from the airport that terrible morning. Almost fifty color photographs of magazine covers hang on the walls of Rice Media Center — most of them are of the Allure and Cosmopolitan variety. Every magazine promises keys to better living – quick steps to fulfilling sex, money, relationships, and social grace; many feature checkout-line grade T&A. Casting dark, gestural shadows, Sparagana occludes our view of most of the images. Violent, scratchy marks tear across the faces of each magazine cover, disrupting the cheery life promised therein, and also the pictoral plane, a strategy Sparagana frequently employs to convey psychic and emotional ruptures. These are uneasy, distrustful photographs that shoot right back at the trappings of desire and of photography itself.

The MFAH’s primary contribution towards the FotoFest effort was the retrospective of Louis Faurer, a New York School photographer who had previously been lost in the dustbin of history. This major exhibition was to introduce him to the public anew, which it did. And it did. And it did. The show is enormous and would be better served at half its current size. Faurer, a friend and contemporary of Robert Frank, does indeed deserve to be rediscovered; he was a very, very good photographer. His melancholic street photographs of New York are as good as any made during the period. With such little public awareness of his work, though, it is lost on me why we need to see what looks like everything he’s done, including so many terrible prints made from copy negatives (many originals were lost), when the public interest isn’t there. I’d rather be introduced to his first-rate work first, and then go digging through the proverbial cutting room floor to see what was left aside. I guess that’s why Time Magazine didn’t name me curator of the year, though.

Upstairs, in the small works-on-paper gallery, Anne Tucker [MFAH Gus & Lyndall Wortham Curator of Photography and Time Magazine Curator of the Year] presents a small group exhibit of Postwar Italian Photography. Sounded like a snoozer to me, but this small, dare I say, classical, show wound up shocking me with its bold visions that were without parallel in America photography at the time. While Faurer’s photographs of the same time look so familiar to us, as they were made in a very narrow tradition (lonely people on the sidewalk), this Italian work, made alongside the Neo-Realist film movement, provides a breath of fresh air. The most famous photographer, Mario Giacomelli, has a wall to himself, with samples from his major bodies of work. His photographs of the elderly — wrinkled, saggy, and ever still, look straight out of paintings by Bruegel or etchings by Daumier. Antonio Masotti, the “original paparazzi”, after whom Fellini coined the term, is included in the show. Known for being the first celebrity-hound to provoke the stars for more dramatic shots, it is amusing to see the early beginnings of this multi-million dollar photographic industry. Other highlights include Mario Carrieri’s high-contrast ultra-graphic shot of a checkerboard racing car, Nino Migliori‘s all-over abstractions, and one of the most sumptuous photographs of Venice I’ve ever seen.

Aside from the John Haddock, Larry Clark and Jeremy Blake exhibits, which have already been reviewed on Glasstire, these small exhibits stick out as the diamonds-in-the-rough shows of FotoFest 2002. By my tastes and count, that’s six outstanding shows in a field of 170. Sound low to you, too? Well, It helps me to think of it this way: there are now 6 exemplary photo exhibits in Houston, and another half-dozen or so definitely worth checking out, and I can’t think of when that’s happened since…I don’t know — last FotoFest?

Images courtesy the artists.

Chas Bowie is an artist and writer in Houston.