The world premiere of Claude Wampler’s new film, Ambulance, was a disaster from the outset.

The main DiverseWorks gallery featured two film projectors facing the east/west walls, and a octagonal arrangement of chairs facing outward, radiating from the center. After the artist’s introduction, the lights were turned off for the screening, except for one row of tracks which wouldn’t go dark. Flip all the lights back on, then off again. Still the lights shone. A few people giggled as Wampler impatiently hollered “Black! Black!” to the volunteer techs in back. After several minutes the row of lights went off except for one stubborn bulb, shining brightly in the corner. It was impossible not to feel bad for the poor DW workers who were scrambling around in the semi-darkness, looking for the one switch that would darken the main gallery. The artist looked as if she might go out of her skin any second.We were running late, and this reeked of ill-preparedness.

This is not how anyone would want to begin their world premiere, to be sure. Just days before at the Glassell School of Art, almost the exact same thing occurred at Sharon Lockhart‘s lecture, when she tried to show a video, but the audio component refused to cooperate. What is this rash of A/V deficiency sweeping our art community? Finally, all the lights went out! Someone wisely thought to switch off the breaker to the whole gallery. Good back-to-basics strategy, I thought. Except that with no power in the room, how was the projector to run? Oh man, all lights back on. The crowd roared in applause, as they do when waiters drop trays loaded with somebody else’s food. Patrons began to mill about, sensing no resolution in sight. The scene looked like a freeway, two miles south of a pile-up, bored passengers stretching their legs, angling for a better view. DW staffers came running out of closets with extension cords; Claude Wampler looked ready to either kill or cry. The woman in front of me called out to the artist as she ran by “don’t worry — we’re having fun!” Her husband dryly noted “she’s not.” Truth was, I wasn’t having much fun either. We were about 20 minutes late, and I was losing my interest in sitting through any movie. I signaled to Andrea Grover of Aurora Picture Show to go help out with the projector. After all, I’ve never seen any calamity like this at Aurora before, but Andrea seemed frozen in sympathetic panic for the artist. Doesn’t anybody do dry runs anymore?

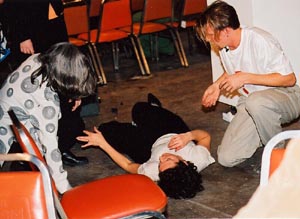

DW curator Diane Barber (l) and a DW staffer try to console a supine Wampler as the situation deteriorates

Then, as if it couldn’t get any worse, the other proverbial shoe fell. Except in this case, it was one of the two film projectors. In all the hustle and bustle, one of the loaded projectors crashed to the floor with an astonishingly loud explosion. Oh shit. Looks like we weren”t getting a movie at all that night. About a dozen people just got up and walked out at this point. I couldn’t really blame them, except that I was morbidly fascinated by how any artist would pull out of this one gracefully. It became clear that Ms. Wampler would not be the one to show me. As she and a DW staffer were crawling around on the floor trying to salvage the film reel from the mechanical wreckage, I heard her cry out “Of course you can’t Scotch tape it, you fucking idiot! It’s my only film!” Hey now. As bad as I felt for this artist, whose world premiere could seemingly not get any worse, nobody deserves to be called a fucking idiot, especially someone working at a non-profit art organization. Before I could protest, another crash from the other side of the room. An older (to me) gentleman had fallen over his chair & was sprawled out across the bent metal. Dolan Smith jumped up to help out, but the guy looked unharmed, just embarrassed.

The tension in the room had already risen to a heavy, swollen pitch, and then a series of events occurred bordering on catastrophic. Behind me, a guy started screaming and cursing while Vicki Perez tried to eject him from the building. He looked like he was trying to get back to his chair for his coat or date or something, but Vicki was blocking his way. In anger, he punched a hole through the gallery wall. What on Earth was going on? This must be what Friday the 13th is like in hell. I figured this was the point when I should jump up and help Vicki, but this guy outweighed me by about a hundred pounds, and frankly, I’m nobody’s hero. Meanwhile, Vicki had put some kung-fu grip on this guy’s wrist and had taken him down to the ground. Go Vicki! But across the room, somebody had splashed red wine all across the gallery wall, and in another corner, a small fire had started and was stinking the place up. Clusters of people were laughing at all the mayhem, and I mistook it for nervous laughter, that inappropriate defense against fear. And I came to realize I was smack in the middle of Claude Wampler’s world-premiere performance of Ambulance, snagged hook, line, and sinker. Right?

Chaos surrounded me, and while I was pretty sure everything was a hoax, I didn’t want to end up cackling at some guy whose femur was sticking out of his trousers. I met eyes with one of the curators from the Contemporary Arts Museum and we held each other’s gaze for a second, unsure whether to laugh at the relief of having been duped, or to run screaming down the road calling for 911. As if to answer our confusion while simultaneously increasing the anxiety level in the room, an ambulance siren went off in the gallery, as if it had always existed, just in case someone got hurt. At this point, the artist was sobbing and heaving, until tears turned to gasps and she passed out in the middle of the wreckage. One concerned audience member, not a “plant,” ran to her rescue but was pushed away by DW staffers. They screamed for someone to call 911, who arrived in a matter of minutes. EMS came in and loaded Wampler onto a stretcher, then raced her away, sirens wailing in the dark night. DW Director Sara Kellner, with frazzled poise, apologized for all the troubles and dutifully noted that Ambulance would obviously not be shown that night, but rescheduled for later in the month. Calm had been restored to the gallery, but for the siren’s cry, and there was nothing left to do but to file out and mingle on the loading docks.

Everyone claimed not to have been fooled for long, but judging from all the facial scenes I saw in the gallery, they were lying through their teeth. This had been a very well coordinated and convincing hoax pulled off by at least a dozen people with a collective flair for timing and chaotic drama (let’s hear it for 501©3 art workers!) . It was not until the wee end of the program, when the catastrophe reached cartoonish levels that the hoax revealed itself. I, for one, had been taken for a heart stopping ride. I was impressed.

Once the adrenaline wore off, and I caught my breath, the piece began to nag at me the way I wish more pieces would. What the hell had happened in there? John Cage’s 4″33″ came to mind, with the embarrassingly slow false-starts of Ambulance — the audience giggling nervously, shifting, and then the gradual awareness that they were in the thick of the piece as they awaited it. 4″33″ was like a peaceful sit-in compared to this neo-Futurist thrill ride, though. Perhaps this is what Cage’s piece would have been like had Jerry Lee Lewis performed it, pouncing and whooping on his piano as it burned to the ground.

And what of this mayhem-for-art’s sake? Wasn’t it just 3 or 4 months ago that our country collectively called for a moratorium on action movies with gratuitous violence and explosions? Were we now, as part of a more “enlightened” art audience, getting our guffaws at this simulation of disaster and violence? Gore Vidal‘s phrase “United States of Amnesia” resounded in my skull. During the performance, while people were screaming in a crowded room, (controlled) fires burned, stretchers were wheeled in, and sirens overpowered everything, was I not to think of the all-too-real disasters and tragedies of September 11? Did a ruined art opening seem like any real tragedy? Of course not (it hadn’t happened to me, after all). Could I forgive Wampler for screaming “Fire” in a crowded gallery? Was there a reason this piece didn’t premiere in New York?

The next day I revisited the gallery. Four video monitors had been set up in each corner, showing the previous night’s carnage from high corners, like a surveillance camera would. The rest of the gallery was left as it was after the opening — projectors on the floor, along with beer bottles, a rubber, napkins, flyers, and about a dollar fifty. The hole where the guy had punched through the wall looked remarkably fake during the day. There was still wine all over the wall, and the wails of sirens from the videos. It was a straight-up wreckage installation, looking like the morning after a hurricane or an out-of-control kegger. But as if to break any illusion of true disaster, there were now wall labels where each incident had taken place — where the guy’s nose gushed blood and where the wall was torched and still smelled of carbon. And looking at the sloppy pre-production sketches in the small gallery, one could make out a water stained list, a role-call of all the mini-tragedies needed to pull Ambulance off. Projector doesn’t work. Projector smashes. Man falls down. Guy punches through wall. Vicki tackles. Wine thrown on gallery wall. Men fight. Ambulance comes. It was a recipe board for a lapstick disaster verité. Simulate panic, and the real thing will ensue. Stir and enjoy. For those who maintain that irony died on September 11, Wampler’s piece shows that for good or ill, irony still rages, howls, and snickers through our kunsthalles and even through our ambulances.

Images courtesy the artist and DiverseWorks.

Chas Bowie is an artist and writer in Houston.