I confess: I myself show at Inman Gallery, so if you feel that this invalidates my opinion of other work shown there, you can stop reading now.

John Pomara’s glossy enameled panels are competent, affectless, impersonal. In the past I have used the phrase “toxic pond sludge” (I meant that in a good way) to describe Pomara’s abstractions, but these new works at Inman gallery are cleaner. The panels are either black or white; the black ones suggesting nighttime landscapes, time-lapse photographs of headlights on a rain-slick city street. The proportions of the white panels suggest sheets of milky paper, squeegeed into horizontal zips like writing.

In both cases, the vertical orientation of the panel counteracts the horizontal stretch of the painting. Compare these works to Barnet Newman‘s: if Newman’s vertical zips are the figure reduced to its essential gravity-defying assertion of existence, Pomara’s horizontal streaks are the equivalent distillation of landscape, stretching flat and sliding sideways at high speed.

Although they are emphatically about the glossy deliciousness of industrial paint, Pomara’s works don’t feel like paintings. Their exposed edges show that each is a thin sheet of aluminum laminated to birch plywood. The panels seem manufactured, not painted: the result of the impersonal operation of chance and technique.

The odd, syncopated hanging of the show does a lot for the work; irregular intervals between the panels make them into a sort of Morse code: intermittent, static-laden signals on the information superhighway. In the entranceway, a large black panel is hung next to a similar small one, upsetting one’s expectations of typical gallery-style installation. The two panels have an odd relationship: a large and small version of the same thing, or possibly one close-up and one far away.

A discussion of Pomara’s work is incomplete without referencing the very similar works of Houston artist Tad Griffin, Pomara’s former student. Their co-existence is an opportunity to make subtle comparisons that highlight nuances of both artists” works, which are usually submerged. Here we are comparing, not pears and oranges, but Bosc vs. Bartlett. Both Griffin and Pomara swipe intermittent stripes of black and white paint across aluminum panels. Pomara’s recent works are more pictorial: his streaks condense at the middle of the panel to imply depth, demarcating foreground, middle, and background; Griffin’s all-over patterns are a depthless skin stretched across the surface of his paintings. Griffin’s intervals are regular, but not mechanical; he is a man imitating a machine. Pomara’s irregular compositions of stripes and gaps are the opposite: a painter using mechanical techniques to depersonalize his pictures. If we can collect one or two more Texas squeegee painters we’d have a school!

Biblilotech

Co-curated by Brooke Stroud in Houston and Tim Litzmann in New York, Biblilotech presents books made by eleven artists on a big table. Unlike many artist book shows, you can touch most of the works, experiencing them as the artists intended. Only a few of the books are hands-off, and they suffer for it. Normally, it is the dealers, not the artist themselves, who emasculate the works by making them inaccessible, but I wish the artists had resisted the temptation to cover their books with plexi.

Artists like the idea of making books, but don’t know what to fill them with. The sequential structure of book pages makes them ideal for narrative progressions like fiction or comic strips; for the more visually minded, they can also serve as mini-museums, collecting similar items for comparison, as in exhibition catalogs. Nearly all the artists in Biblilotech opt for this second strategy of author as curator.

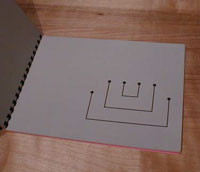

Several artists collect their own obscure, systematic drawings in the classic style of 70’s conceptualists like Sol Lewitt. Marco Villegas collects elegantly spaced pencil lines, Timothy Litzmann collects angular circuit diagrams, Don Voisine collects architectural specks, and best (but most Lewitt-esque of all) Daniel Villeneuve collects permutations of minimalist boxes in pastel colors.

Others use the book format to collect drawings which would otherwise be framed: photocopies of Mark Allen‘s porno cartoons and Michael Kennaugh‘s romantic collages lose something in reproduction.

One of the best pieces, despite its frustrating inaccessibility, is Melissa Thorne‘s 9 Brown Potholders. It’s just what it says, a handsome foldout which collects potholders for comparison. Thorne wisely avoids using her own work as the subject matter of her book.

In Flash, a collection of temporary tattoos, Emily Joyce has found the ideal vehicle for her signature shapes. Relieved of the heavy expectations viewers place on paintings and installations, her colorful, innocuous confabulations make striking, enjoyable body-art.

Bill Davenport is an artist and writer from Houston.